1. Character Profile

Let's look at each Character Profile section separately.

1.a. Meaning

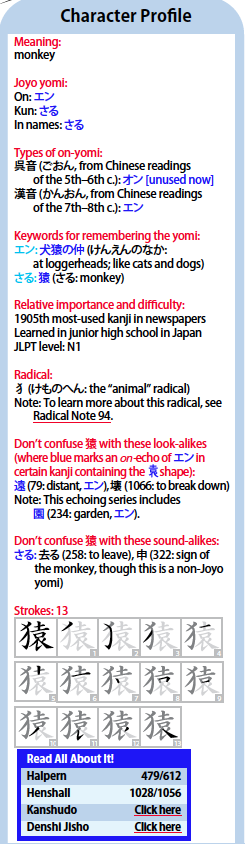

At the top of every Character Profile, you'll find the meaning of the kanji in question. In this case, the Character Profile is from essay 1028 on 猿 (monkey). This kanji also has a few more meanings, as you'll see at the end of the essay, but those are obscure. Only the most important meanings appear in the Character Profile.

1.b. Joyo yomi

This section tells you the mainstream on-yomi and kun-yomi of the kanji in question. (If these terms confuse you, please see the glossary.)

The word Joyo doesn't just dictate which kanji you'll need in Japan; it also tells you the exact yomi you should know for basic literacy. That is, a Joyo kanji often has both Joyo yomi and non-Joyo yomi. For instance, 雨 (3: rain) has one Joyo on-yomi (ウ), two Joyo kun-yomi (あめ and あま), and one non-Joyo kun-yomi (さめ). The Character Profile lists only Joyo yomi. So does each Character Home Page, as you can see on the 雨 page. To know which yomi are Joyo, I originally consulted an authoritative list by the Japanese Agency for Cultural Affairs and then put that information into the Joy o' Kanji database.

The Character Profile also provides the yomi of the kanji when it appears in given names and family names. Can you imagine giving your child a name that includes the monkey kanji?!

If you check Denshi Jisho, you'll see a section called Japanese Names. Just look how many there are for 祥 (1398: auspicious; happiness)! That category might present name yomi that don't appear in the Joy o' Kanji Character Profile. There would be several reasons for this. For one thing, whereas the Japanese Names category in Denshi Jisho includes both place names and personal names, the Joy o' Kanji name yomi listing relates primarily to people's names, particularly to given names. It should be noted, though, that personal and place name yomi are not mutually exclusive. For example, 塚本 (つかもと) can be either a surname or a place name. Also, many kanji have countless name yomi, making it rare to find identical listings in any two dictionaries. The dictionary Kanjigen, which is my primary source for name yomi, presents long lists of them. Given the space limitations in the Character Profile, I've sometimes chosen to share just a few of these. My listings also include any name yomi that I discuss in the essay, usually in photo captions about books and shop signs.

1.c. Types of on-yomi

As the glossary explains in more detail, the Japanese didn't import kanji in one fell swoop but rather in waves. For that reason, one character may now have several on-yomi. The Japanese classify these readings according to the era in which they originated in China (which is not the same as the era in which the character entered Japan). It's hard to say exactly when each kind of kanji originated, because sources differ. To keep things really simple, I've settled on a range of dates. Here's how this plays out for 行 (118: to go):

呉音 (ごおん, from Chinese readings of the 5th–6th c.): ギョウ

漢音 (かんおん, from Chinese readings of the 7th–8th c.): コウ

唐音 (とうおん, from Chinese readings of the 12th c. and onward): アン

If the three yomi differ, you'll find them all listed in this section. If two are the same (e.g., the yomi for 呉音 and 漢音), I'll list only the earlier reading.

There's even a fourth classification. When an on-yomi doesn't belong to any of the three types above, the Japanese call it the 慣用音 (かんようおん), which translates as "traditional (popularly accepted) pronunciation." For example, 茶 (171: tea) has a 唐音 of サ and a 慣用音 of チャ.

I've been puzzled to find some 慣用音 that have fallen out of use. How can something be both popular and obsolete? The answer lies in a statement from the publisher of the dictionary Kojien. He says that 慣用音 just represents a reading that cannot be accounted for using the phonetic rules of 呉音, 漢音, or 唐音. Only some 慣用音 are popularly accepted, whereas others are not. Therefore, 慣用音 is a rather misleading term. Aha!

With so many on-yomi floating around over the centuries, it's not surprising that the Japanese have stopped using quite a few. I indicate this state of affairs with "unused now," as you can see above. Because of space constraints, this label can be confusing when there are two on-yomi for a particular era. Here's an example from essay 1110 on 寛 (broad; magnanimous; lenient; relaxed):

At first glance, it might look as if all three on-yomi have become obsolete. But in fact, カン is the Joyo on-yomi; "unused now" pertains only to フ and フウ.

When a kanji lacks a Joyo on-yomi, the essay will still list the old type of on-yomi, if it exists. For instance, 芝 (1335: lawn grass) has no Joyo on-yomi, but the Character Profile displays the 呉音 of シ.

The Japanese created some characters (known as kokuji), such as 峠 (1663: mountain pass). Because this kanji never existed in China, it has no on-yomi, and I excluded the "Types of on-yomi" section from the Character Profile of that essay.

1.d. Keywords for remembering the yomi

I find it hard to make random syllables stick in my brain. For me, it's much easier to remember a yomi by coming up with a word that contains it. For instance, if you think of 茶 and try to conjure up two on-yomi, you might remember チャ but draw a blank about サ. By contrast, you can more readily associate 茶 with these two yomi if you think of how to say "tea" (お茶, おちゃ) and "cafe" (喫茶店, きっさてん). In each Character Profile, I present keywords that you're likeliest to hear, know, use, and remember. In the image here, the first keyword is 犬猿の仲 (けんえんのなか). I chose this because the rhyme of けん and えん aids the memory. I also try to pick words with unvoiced versions of the yomi, though I do make exceptions. My choices are subjective; if they don't work for you, by all means pick your own!

1.e. Relative importance and difficulty

From data that Jack Halpern of the CJK Dictionary Institute kindly gave me, we learn that 猿 ranks 1905th out of the kanji most often used in newspapers. Poor, lowly monkey! By "newspapers," I specifically mean the Yomiuri Shimbun, the most widely circulated newspaper in the world! In extremely rare instances, when there's no information about how often the Yomiuri Shimbun uses a particular kanji, I'll cite frequency data for the Asahi Shimbun instead.

So much for the "importance" of a particular kanji. Now for its "difficulty." For concision, I've used "difficulty" in the heading to indicate when Japanese students learn each kanji in their academic careers. In the case of 猿, the answer is "junior high school." (After sixth grade, students don't need to learn a particular set of characters each year. Rather, they have until the end of junior high to do so.) As noted in the FAQ About JOK ("Which Characters Will Joy o' Kanji Essays Examine First?"), junior high kanji aren't inherently more difficult, or not always. We just tend to think they are!

Note that as of January 10, 2025, I will gradually be removing such statements from essays. Grade assignments for kanji periodically change (for instance, all prefecture kanji are now taught in elementary school, whereas that wasn't true before), and it's neither feasible nor sensible to keep altering that information in my essays. After all, most of us don't need to know whether a certain character is taught in 3rd grade, 6th grade, or junior high school.

As for the JLPT level, this refers to the Japanese Language Proficiency Test, a standardized exam administered in Japan and around the world. The test currently has five levels, where N5 is the easiest and N1 is the hardest. (The N stands for "new.") To pass N1, you need to know all the Joyo kanji.

As the image shows, 猿 would most likely appear only in the N1 test. Most likely? Yes. The JLPT authorities refuse to issue official lists of the kanji needed for each level because they want you to learn everything. (No sweat, right?!) Many of the JLPT listings in Joy o' Kanji have come from the long-established Yoshida Institute and should be fairly reliable. Nevertheless, you should take this information with a grain of salt.

In any essay about a Shin-Joyo kanji (that is, a kanji added to the Joyo set after 2010), I've said that the JLPT level is N1 (which is a change because I previously said "Unknown at this time"). This is an educated guess.

1.f. Radical

Each kanji has a radical. In the case of 猿, the radical is 犭, known in English as the "animal" radical and in Japanese as けもの. In 猿, this radical appears on the left-hand side of the kanji, the position known as へん. Thus, the name of the radical in 猿 is けものへん.

The link takes you to Radical Note 94, which is all about the "animal" radical. This free essay is one of many Radical Notes, each of which focuses on one radical.

To know much more about radicals, see Radical Terms. For more on the left-hand side of a kanji, which is the most common place to find a radical, see essay 1782 on 偏 (one-sided, biased, inclined, partial; left-hand radical).

1.g. Don't confuse 猿 with these look-alikes

This section helps you avoid mixing up the kanji in question with "look-alikes." By "look-alikes," I mean kanji that look so much alike that you may confuse them. Even if they're different enough that you're unlikely to mix them up (e.g., 又 and 双, which respectively mean "again" and "pair"), the list may prompt you to make a mental note of their similarities and differences.

For each kanji listed in this section, you'll see a Henshall number and a definition. The definition part is self-explanatory; for instance, 遠 primarily means "distant." I've explained the Henshall number in the FAQ About JOK, in the section "What Are the Numbers Associated with Each Kanji?" As I've said there, I gave each kanji the number Kenneth Henshall assigned it in the first edition of A Guide to Remembering Japanese Characters. Those numbers changed in the later edition of his book, so our numbering systems no longer match.

The blue in this section signifies an on-echo, a coinage of mine that I explain at length in the glossary. When a particular on-yomi such as エン echoes through a series of kanji with shared shapes, noting the pattern can make it easier to remember the yomi for that series. On top of that, it's fun to find patterns among kanji and to remember that there's an underlying system, not the complete mess that one sometimes perceives!

When characters in an echoing series (e.g., 園) don't look enough like the main kanji (猿, in this case) to risk mixing them up, I list the echoing characters in a special note, as shown in the image.

There are complex patterns to admire throughout Japan!

Sometimes the echoing shape is a Joyo kanji, but it could just as easily be a non-Joyo kanji or not a full character at all. Furthermore, the common shape may not have the same yomi as the kanji in the echoing series. I've handled the various situations as follows:

• The list as a whole is in numerical order, but if an echoing shape happens to be a Joyo kanji, that character appears first in the list, most likely disrupting the numerical sequence. That's the situation in essay 1643 on 倒 (to topple; fall; collapse; turn upside down), where you'll find this:

As you can see, the echoing shape, 到, shares the on-yomi トウ with 倒.

• When the repeating shape is a Joyo kanji that does not share the echo, the shape goes to the head of the list but isn't in blue. For example, see essay 1590 on 彫 (to carve; sculpt; chisel; tattoo):

The repeating shape, 周, has the Joyo on-yomi シュウ, not チョウ.

• If a shared shape is not a Joyo kanji, there should be a statement about that, as in essay 1782 on 偏 (one-sided, biased, inclined, partial; left-hand radical):

• If a shared shape is not even a full kanji, you won't see any references to a non-Joyo shape, and the common shape won't appear in the list. That's true in essay 1214 on 剣 (sword; doubled-edged sword):

1.h. Don't confuse 猿 with these sound-alikes

"Sound-alikes" are kun-yomi homophones. In the Character Profile for 猿, I've listed two other Joyo kanji with the Joyo kun-yomi of さる. I excluded 然る (528: a particular) because, even though you can read it as さる, that kun-yomi is non-Joyo.

The kun-yomi homophone 去る means something quite different from 猿. Often, though, kun-yomi homophones practically share meanings, as you can see with the closely related word 申る, which relates to monkeys in a zodiacal context.

Even native speakers struggle to differentiate many kun-yomi homophones, so it's useful to be aware of the "rivals" for the kun-yomi at hand. By contrast, although there are also scads of on-yomi homophones, they tend to have entirely unrelated meanings. For that reason, there's no need to list on-yomi sound-alikes.

There's one other gray area when it comes to kun-yomi sound-alikes. It's the matter of voiced yomi. That is, 殻 (1075: shell) has the Joyo kun-yomi から. When this kanji pops up in words such as 貝殻 (かいがら: seashell), the から turns into がら. Should we also count がら as a Joyo kun-yomi, and should I therefore list it as a sound-alike for 柄 (1776: character), which has the Joyo kun-yomi がら? There would certainly be good reasons to do that; when it comes to 殻, native speakers perceive から and the voiced がら as part of the same package. Just to keep things as simple as possible, though, I have opted not to list voiced yomi as sound-alikes.

1.i. Stroke count and stroke order diagram

The stroke count tells you how many strokes each character has—13 in this case.

Each stroke order diagram (created by talented graphic designer Tiara Marina) indicates how to draw the kanji in question. The first box shows the complete kanji. In the next box, the character becomes light gray, except the first stroke, which is black. In the subsequent box, the first stroke is dark gray and the second stroke is black. By looking at the progression of boxes, you can see how to build the character, stroke by stroke.

In some cases, the typed form of a kanji differs significantly from the shape of a handwritten character. The stroke order diagrams in Joy o' Kanji reflect handwritten shapes.

After seeing the diagrams, you may have questions about the direction of the strokes. Generally strokes go from left to right and from top to bottom, but diagonal strokes can cause confusion. When you're uncertain, you may want to watch a stroke order animation. These are available on several websites, such as Jim Breen's dictionary.

1.j. Read All About It!

For further reading, I refer you to four fantastic sources of information:

Halpern: There are two numbers (e.g., 479/612) because there are two editions of The Kodansha Kanji Learner’s Dictionary, edited by Jack Halpern. The first number refers to the 1999 edition, whereas the second reflects the numbering in the revised and expanded edition of 2013. Either version of this portable dictionary indicates the meaning of each kanji in particular compounds. That is essential information, as the definitions of characters can change from word to word. You will also see listings such as 479/612 for Halpern numbers in the Mini Profile of every Character Home Page.

Henshall: Again, there are two numbers because there are two editions. First came Kenneth G. Henshall's A Guide to Remembering Japanese Characters. This book presented the etymology of individual characters, exploring the way the meanings and shapes of kanji have changed over time. The updated version is The Complete Guide to Japanese Kanji: Remembering and Understanding the 2,136 Standard Characters. I say more about both editions in Further Resources in the section called Textbooks and Reference Books About Kanji. You will also see listings such as 1028/1056 for Henshall numbers in the Mini Profile of every Character Home Page.

Kanshudo: Kanshudo is Joy o' Kanji's partner and provides innovative games to help you master the material in each essay. You can also buy Joy o' Kanji essays from that site. The Kanshudo creator has anticipated every need a kanji learner might have and provides scads of resources. The site has an innovative way of assessing your current level of kanji knowledge and will present you with tailor-made study recommendations. Other features include lessons for people of all levels; flashcards; functions to help you study kanji and vocabulary according to their JLPT level; a comprehensive word dictionary; and a component-based kanji lookup system.

Denshi Jisho: This online dictionary presents great amounts of information in a concise, attractive way. The outstanding feature is the array of possible components that enables you to search for unknown characters.

In Joy o' Kanji, you'll see shorthand references to these works and others. For instance, I refer to The New Nelson Japanese-English Character Dictionary simply as Nelson. Further Resources supplies more information about that book and more.

2. Etymology Box

The information in the Etymology Box generally comes from three sources: Kenneth Henshall's Guide to Remembering Japanese Characters; (2) the updated version of that book, now called The Complete Guide to Japanese Kanji: Remembering and Understanding the 2,136 Standard Characters; and (3) Kanjigen (which is written in Japanese).

The ancient versions of the characters come to you from Richard Sears's website Chinese Etymology. Sears has categorized his images by historical styles (that is, the way the characters look in artifacts from various eras). Here's the breakdown:

oracle characters: 1766 BCE to 1122 BCE

bronze characters: 1122 BCE to 221 BCE

seal characters: 221 BCE to 200 CE

LST seal characters: dates unknown

For more information about these historical styles, see the glossary ("Old-Style Scripts, Yojijukugo, and Kokuji").

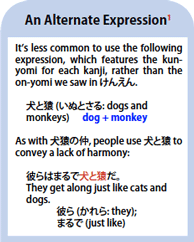

3. Other Sidebars

The Character Profile and the Etymology Box are just two of the many sidebars you'll see in Joy o' Kanji essays. Sidebars usually elaborate on parts of the main text.

Because of design constraints, a sidebar can't always appear alongside the relevant text. Superscript numbers in both the main text and the sidebar titles clarify which pieces go together. If you see text marked with 2, look for a sidebar title featuring 2.

The Character Profile and the Etymology Box are unnumbered sidebars, and they're not the only ones. Sometimes a sidebar is unnumbered because it doesn't relate directly to any part of the main text but rather examines the central theme or the main kanji from another point of view.

4. Sample Sentences

Joy o' Kanji essays abound in sample sentences, followed by vocabulary. You can see this in the text above, which is from essay 1028 on 猿 (monkey).

To make the presentation as concise as possible, I don't include the する of する verbs in vocabulary lists; instead, I define their noun forms. For instance, a sentence in essay 1166 on 狭 (narrow, cramped, tight, constricted) contains 就職する (しゅうしょくする: to find employment). The vocabulary list says "就職 (しゅうしょく: finding employment)," bearing no trace of the する. One can almost always take the noun form and deduce the meaning of the する verb form. When that proves tricky, I supply the する after all.

In lists of definitions, I also provide the dictionary form of verbs such as 買う (かう), even if 買った appeared in the sentence. I similarly present adjectives in their "purest" forms, without inflections such as -かった.

For the most part, I don't define words that appear in hiragana; you probably know many of those terms. Sometimes, though, the words in hiragana can be quite puzzling, so I clarify them when it seems necessary.

Within an essay, if vocabulary repeats in sample sentences or in photo captions, I define the word only the first time. Let's say there are two instances of 彼女 (かのじょ: she, her). An asterisk will accompany the initial definition of 彼女, signaling that this word will recur later in the PDF—minus the definition. Here's where this gets tricky; the first occurrence may be in a sidebar or photo caption, which you may have skipped, preferring to read straight through the main text. Most likely, only common words such as 彼女 will repeat in an essay, and you're bound to know such vocabulary already, so it's doubtful that you'll be left high and dry.

5. Quick Quizzes and Verbal Logic Quizzes

Joy o' Kanji quizzes challenge you to consider the meanings of individual characters and to guess what they would produce when yoked together in a word. Generally, these quizzes don't test you on any prior knowledge of kanji, though sometimes they do. The idea is just to have fun by seeing things from an unexpected angle.

There's no real difference between a Quick Quiz and a Verbal Logic Quiz. However, a Quick Quiz occurs somewhere within the essay, affording a small break. By contrast, a Verbal Logic Quiz signals that the end has come (but not in any dire way!).

By the way, the quiz shown above is from essay 1028 on 猿 (monkey). Check that free essay for the answer!

6. Footer

The footer reflects the number of the particular essay. There's also a copyright symbol in the footer, always a nice thing to observe! Along with the publication information you'll often find a version number, which is simply an in-house way of tracking which copy of the PDF I've posted. If there has been a major revision, I bump the number up from, say, 1.0 to 2.0. If the changes are minor, then 1.1 will change to 1.2, for example.

7. Images

When you get caught up in thinking about etymology, yomi, shades of meaning, and so on, you can forget to admire kanji as visual treats. You'll find several kinds of images to enjoy in the PDFs.

Every essay features a Font Foursquare:

These images (from the website Moji Tekkai) show the very different shapes that kanji can acquire, depending on the font.

You'll also see plenty of photos of signs featuring the main kanji and likely several other characters (as kanji tend to pal around together). Here's a photo from essay 1335 on 芝 (lawn grass):

Other images show the item in question—not the 猿 shape but the shape of a 猿:

Can you see the photo credit? Christopher Acheson has generously supplied many wonderful photos. Others have come from Kevin Hamilton, from me, or from other people, always credited just below the photo.