140. The "Grass" Radical: ŤČĻ and ŤČł

The "grass" radical, ŤČĻ, is as graphically simple as can be. And yet, just as tall grass may hide such realities as slithering snakes, so too does the "grass" radical.

Snake in the Grass: Parent and Variant

The three-stroke ŤČĻ is actually a variant of the outdated, six-stroke parent form ŤČł. In the past, ŤČł appeared in characters instead of the simplified ŤČĻ. That is, whereas Ťäč (1011: potato; sweet potato; taro; yam; tuber) is the modern form, the old style looked like this version from Richard Sears's page:

Seal-script version.

I must admit that the ancient shape looks much more plantlike than the rigidly linear Ťäč.

Nowadays, no one uses ŤČł as a part of other kanji. It exists solely as the non-Joyo kanji ŤČł („āĹ„ā¶, „ĀŹ„Āē: grass, plants), which nobody uses either. Nevertheless, in the train station in Basel, Switzerland, a sign for a tea shop has the old form of the grass radical in the ŤĆ∂ („Ā°„āÉ: tea) kanji:

Photo Credit: Eve Kushner

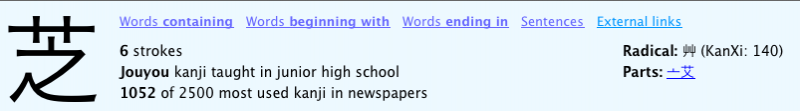

Furthermore, some dictionaries (e.g., Denshi Jisho) present ŤČł (rather than ŤČĻ) as the radical of, say, ŤäĚ (1335: lawn grass), as you can see here on the right side:

The tea shop sign is charming, but when it comes to dictionaries I feel that this adherence to the old ways sets kanji learners up for confusion. After all, the ŤČł shape is not visible in ŤäĚ or any other characters with the "grass" radical. To avoid this problem, Joy o' Kanji treats ŤČĻ as the parent and ŤČł as the variant. There's one other variant, as well:  . It's not always electronically supported, so I've inserted an image here. Also, it may look indistinguishable from ŤČĻ, but this four-stroke variant actually consists of two plus signs, side by side.

. It's not always electronically supported, so I've inserted an image here. Also, it may look indistinguishable from ŤČĻ, but this four-stroke variant actually consists of two plus signs, side by side.

Yomi of the Radical

You can call any version of the "grass" radical „ĀŹ„Āē„Āč„āď„āÄ„āä if the radical sits atop a kanji, as it almost always does. Otherwise, you can use the names „ĀŹ„Āē or „ĀĚ„ĀÜ„Āď„ĀÜ. You might think that this „ĀŹ„Āē comes from the yomi of ŤČł. Instead, here's the way to write „ĀŹ„Āē„Āč„āď„āÄ„āä (or „ĀĚ„ĀÜ„Āď„ĀÜ) in kanji:

ŤćȌ܆ („ĀŹ„Āē„Āč„āď„āÄ„āä or „ĀĚ„ĀÜ„Āď„ĀÜ: "grass" radical on top of a kanji) grass + crown

As it turns out, ŤćČ (162: „āĹ„ā¶, „ĀŹ„Āē: grass, plants) has the same meaning and many of the same yomi as ŤČł. In fact, the Japanese have long used ŤćČ in place of ŤČł to mean "grass."

Grass and Water

Another peculiarity of the "grass" radical is that it pairs up with the "water" radical śįĶ in at least 23 kanji (both Joyo and non-Joyo), including these Joyo examples:

ŤźĹ (408: to fall)

ŤóĽ (1531: duckweed, seaweed)

ŤĖĄ (1699: weak)

Ťó© (1721: feudal domain)

In all these cases, ŤČĻ is the radical and śįĶ is just a component. You can even tell that from the structure of the characters; the grass stretches out over the whole kanji, as if to assert its dominance, while the water plays a more subservient, supporting role, tucked underneath.

On the flip side, we find these two Joyo characters:

śľĘ (442: Chinese)

An all-important kanji in our study of śľĘŚ≠ó!

śľ† (1700: desert; vague)

Both water and grass in a desert?!

In these instances, the water protrudes past the grass and serves as the radical.

Big Sun

Those two kanji, śľĘ (442) and śľ† (1700), look alike, don't they?! if you take the latter one and remove the water, you produce a Ťéę configuration that recurs inside several kanji with "grass" radicals:

ŚĘď (788: grave, tomb)

ŚĻē (977: curtain; (theater) act; shogunate)

ś®° (980: to copy)

Śčü (1787: campaign; to enlist)

śÖē (1788: to adore; admire)

śöģ (1789: to live; earn a livelihood; grow dark; come to an end)

ŤÜú (1834: membrane)

Many kanji in this list have the on-yomi „Éú, and we can thank Ťéę for that on-echo.

Meanwhile, if we return to the other look-alike, śľĘ (442: China), we can observe that it shares a prominent component with the following character:

ŚėÜ (1566: to grieve)

The etymology of these right-hand sides is obscure, says Henshall, and they have no grass connection.

Ultimately, the takeaway from comparing śľĘ (442: China) and śľ† (1700: desert) is to notice that although they do look quite similar, they actually belong to different families, where we can find other patterns (and a heap more confusion)! A snake in the grass indeed!

The Position of the "Grass" Radical

We've seen that the "grass" radical tends to lie at the top of a character. In fact, when it stretches across the crown, it's almost certain to be the radical:

ŤĆ∂ (171: tea)

ŤĖ¨ (398: medicine)

ŤäĹ (434: bud)

Conversely, when ŤČĻ is tucked away inside a character, it does not function as the on-duty radical:

ŚĮõ (1110: broad)

ŚĆŅ (1664: to conceal)

ŚĘ≥ (1771: grave mound, tomb)

śÜ§ (1772: indignation)

Similarly, when ŤČĻ is shunted to the top right or top left of a kanji, it doesn't function as the radical:

Śāô (774: to equip)

You know this kanji from śļĖŚāô („Āė„āÖ„āď„Ā≥: preparation).

Śč§ (842: to be in the service of)

You're likely familiar with Śč§„āĀ„āč („Ā§„Ā®„āĀ„āč: to work for, be employed at).

ťõ£ (949: difficult)

This helps to form ťõ£„Āó„ĀĄ („āÄ„Āö„Āč„Āó„ĀĄ: difficult).

śÖĆ (1259: hurried; flustered; panic)

Ťęĺ (1557: agreement)

Ś°Ē (1651: tower; pagoda; monument)

śź≠ (1652: boarding; loading (vehicle))

In two Joyo kanji, ŤČĻ is so small that it's almost impossible to spot. Look for it (really hard!) in the upper left corner:

Ť≠¶ (847: to guard against, warn, admonish)

ť©ö (1172: to be surprised)

You know this as ť©ö„ĀŹ („Āä„Ā©„āć„ĀŹ: to be surprised).

In both instances, the unit to consider isn't ŤČĻ but rather śē¨, a kanji in its own right:

śē¨ (846: respect)

Inside śē¨, the ŤČĻ probably has no real relation to grass; Henshall says it might have represented a "headdress made of sheep's horns"! In Ť≠¶ and ť©ö, then, it's appropriate that we can barely spot the grass because there's nothing grassy about it. Furthermore, grass doesn't serve as the radical in either kanji. To put it another way, the grass is definitely greener in other kanji.

Where's the Plant Life?

Rather than considering the "grass" radical in characters as obviously connected to plants as ŤäĪ (9: flower) and ŤĎČ (405: leaf), I find it far more compelling to see why grass would be growing in some unlikely kanji. I'm talking about the following Joyo characters for which all but one etymology has come from Henshall:

Ťć∑ (239: load, burden)

The kanji originally meant "lotus" but, in Japanese, it has grown far from that. The journey to "load, burden" is disputed.

Ťäł (470: art, craft, skill; to plant)

This character can mean "to plant"! I didn't know that! What's more, śú® (tree) appeared inside an early version of this kanji. According to Henshall, "planting a tree" was associated with "horticultural skill," which later became "skill" in general, then "artistic accomplishment."

Ťč• (886: if; young)

The plant here has to do with a miscopying of another shape.

Ťíł (904: steam)

Initially, the shape depicted "hands throwing brushwood on a fire." The "grass" radical represented "brushwood." Where there's fire, there's steam, or something like that. Actually, scholars don't know where the steam came from, as Ťíł contains no water, but someone may have mixed up its innards with śįī (water).

ŤĒĶ (923: to store; storehouse)

This shape originally referred to "concealing a wounded and incapacitated person with grass," which is to say "protecting them." So it's not just snakes that lie hidden in grass.

ŤĎó (937: author; literary work; conspicuous)

Many etymological theories exist. As one explanation has it, ŤĎó first meant "variety of plants," which led to meanings involving "showiness" and "displays." It's possible that "writing a book" is one such display.

ŤŹď (1047: confection; cake; sweets)

"Plant, vegetation" (ŤČĻ) + "fruit" (śěú) yields "fruit" again, says Henshall in his newer edition. In fact, ŤŹď may simply have been an expanded version of śěú in early Chinese. Henshall notes that nowadays the Japanese use ŤŹď to represent confections, not fruit.

Ťćė (1515: villa, dignified)

This character once represented a "place where grass is fertile but kept in order." Where would that happen but at a "country estate" or "villa"?!

ŤďĄ (1579: to accumulate)

Henshall says in his newer edition that the ŤČĻ represents "plants" and that the Áēú may have the extended sense "accumulate," yielding the overall meaning "accumulate vegetables (for winter)." He also cites a theory that the Áēú phonetically conveys "soak skeins in pot of dye," making ŤďĄ mean "accumulate (color from plant dyes)." By contrast, Kanjigen breaks down ŤďĄ as ŤČĻ (grass) + the phonetic Áēú (enclose and keep an animal as livestock), saying that the latter component refers to vegetables that one stockpiles to make it through winter.

Ťčõ (1971: irritation; torment; bullying)

Kanjigen says this radical means "grass," and the ŚŹĮ means "to be bent in the shape of an inverted uppercase L" or "one's voice becomes hoarse." Combining ŤČĻ with ŚŹĮ yields "the kind of plant that irritates one's throat," as well as "an act causing severe friction or stimulation."

Burying the Topic

One final note before we bury the topic of the "grass" radical. Let's consider a kanji where grass is so essential that it occurs twice:

ŤĎ¨ (1523: funeral; to bury)

The bottom component used to be ŤČł and therefore represents "grass" just as much as the ŤČĻ on top does. The middle part, ś≠Ľ, is "death" or "dead person." An ancient practice was to cover a corpse with grass, rather than interring it, so burying involves surrounding a dead person with grass, says Henshall.

The "grass" radical is often related to life and growth, but it can also be associated with death. A full-service radical, I would say!