78. The "Death" Radical: 歹

Death can be unfathomable, but for the most part that's not so with the "death" radical 歹. In particular, this four-stroke shape is fairly simple graphically.

Its names do present complications, but that's also part of the fun (if it's acceptable to connect fun with death!). Take these names:

1. いちた, referring to 歹 as 一 (いち: one) plus the katakana タ

2. がつ, meaning "dried bones," per Nelson

3. かばね, corresponding to the non-Joyo 屍 (corpse)

The がつ in the second name alludes to the yomi of the autonomous non-Joyo kanji 歹:

歹 (ガツ: bare bones; bad; wrong)

Incidentally, because of the first meaning of this character, Breen calls 歹 the "bare bone" radical, as well as the "death" radical.

The Radical on the Left

When our radical shifts to the left side of a character, we can take the names I presented and attach -へん (a suffix meaning "left-side radical"):

4. いちたへん

5. がつへん

6. かばねへん

Those terms apply to four of the five Joyo kanji featuring the on-duty 歹 radical:

残 (493: to remain, stay; leave behind)

殊 (1348: special)

殉 (1377: to sacrifice oneself)

殖 (1426: to multiply)

The fifth Joyo kanji with this on-duty radical is the most closely related to death:

死 (286: death)

In this case the following radical name applies:

7. しにがまえ, meaning "an enclosure like that of しぬ (to die)"

The 死 kanji carries the Joyo readings シ and し•ぬ. I believe the しに in the radical name relates to しぬ, which has しにます as an inflection. Meanwhile, enclosing elements are usually called -構え (-がまえ), so that explains the latter half of the name.

Wow, we have seven radical names and only five Joyo kanji in this category!

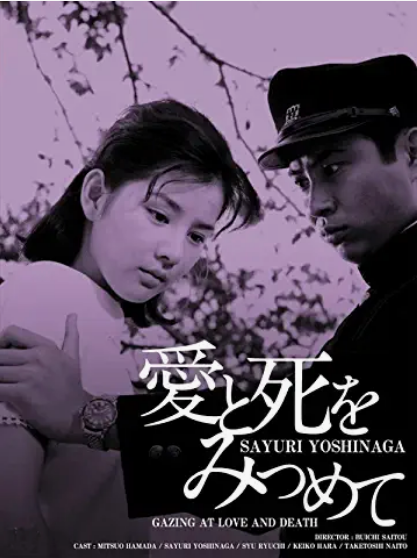

A 1964 movie bears this title:

「愛と死をみつめて」

Gazing at Love and Death

愛 (あい: love); みつめる (見つめる: to gaze at)

Seeing an enlarged version of 死 makes it easier to conceive of our radical as an enclosure.

A Bare Bones Etymology

The "bare bones" sense of the 歹 character initially confused me. My dictionary defines "bare bones" abstractly as "the irreducible minimum; the most essential components." Given the context, though, I imagine that 歹 instead represents a skeleton after the flesh has disappeared.

Indeed, that's what we find with the etymology of this kanji, an analysis that comes from Henshall's newer edition (as all the etymologies below do):

死 (286: death)

The left side of an early form showed "skeletal remains," whereas the right side meant "person" but may have phonetically conveyed "flesh rots and drops to ground." If so, then the whole character represented "corpse turns to bleached bones free of flesh." Alternatively, if the right side implied "divided up into small pieces," then 死 meant "die and bones come apart."

Henshall adds this fascinating fact: "In ancient China a person was only seen as dead when the corpse became a clean skeleton after exposure to weather." Stringent requirements indeed! Did they leave every corpse out to rot before declaring someone deceased? How exactly did it all work?!

As the shape of 死 evolved, says Henshall, the left side changed to 歹, the right side to 匕 (fallen person). He defines that left-hand radical as "meatless bones."

We can now be confident about what "bare bones" means vis-a-vis our radical. There's nothing abstract going on; the explanation is as graphic as can be.

Three More Etymologies

Will we find anything equally gory in other kanji featuring our on-duty radical? Let's see what Henshall has dug up:

残 (493: to remain, stay; leave behind)

The left side represents "bare bones; bone fragments." The right side symbolizes "crossed halberds; injure," also phonetically conveying "cut and wound." Thus, the entire character means "kill by cutting."

殉 (1377: to sacrifice oneself)

The radical means "bone fragment" or "top of spine" and frequently has the connotation "death/serious injury." As the right side phonetically suggests "follow," 殉 as a whole represents "follow in death." Henshall comments that in earlier times, it was not uncommon for men to follow a lord into death.

殖 (1426: to multiply)

Once more, the left side means "bone fragment," as well as "die." The other half may phonetically convey "adhere, be sticky." If so, 殖 symbolizes "flesh on corpse rots and goes mushy." But the right side could instead suggest "rot, decay." Henshall doesn't indicate how that would affect the overall sense. He does note that one scholar sees "increase" (Henshall's definition of 殖) as derived from the interchangeable use of 殖 and 植 (plant), which are homophones in Chinese. That scholar views "increase" as an extended sense from "plant." Aha! I was wondering how death could possibly relate to multiplying or increases, when it is the ultimate form of reduction.