Between the Lines

If you saw the following term, what would you think it meant:

指針 (ししん) finger, toe; to point to; nominate; instruct + needle

In the breakdown I've temporarily listed all the major meanings of 指, though obviously they don't all apply here. Choose the relevant definitions of the compound:

a. needle of a compass

b. clock hand

c. injection

d. guideline

I'll block the answer with a preview of the newest essay:

The correct answers are a, b, and d. Here again is the term, this time with complete definitions and with the proper breakdown:

指針 (ししん: (1) needle (compass, gauge, etc.); hand (clock); indicator; pointer; (2) guiding principle; guideline; guide) to point to + needle

The needle of a compass points to useful information, and a clock hand is needlelike, so the initial meanings make perfect sense.

The "guiding principle" and "guideline" definitions blow me away, though, because 針 makes me envision sewing, not rules of conduct.

The Path

If I had to come up with a kanji representation of "guiding principle," I might choose 道, as it means "path" or "the way," showing people how to conduct themselves in everything from martial arts to religion.

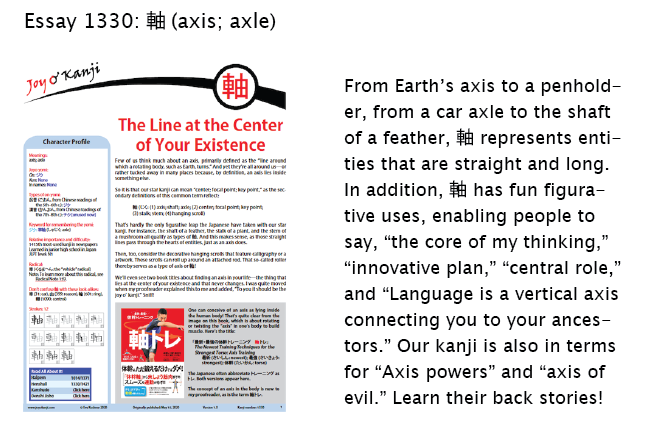

I was therefore intrigued to come upon this book when I wrote essay 1330 on 軸 (axis; axle):

Here's the title, which features the keyword 機軸 (きじく: central part of something):

「思想の機軸とわが軌跡」

The Core of My Thinking and the Path I Took

思想 (しそう: thinking); わが (我が: my); 軌跡 (きせき: path one has taken)

From examining this title I learned that author Takaaki Yoshimoto (吉本隆明, よしもと たかあき: 1924–2012) was famous for his thinking as a poet, literary critic, and philosopher but was perhaps even better known as the father of fiction writer Banana Yoshimoto (吉本ばなな), who made a big international splash from a young age.

I also pondered the father’s thinking in naming her Banana. Wouldn't the“core” of his thinking have inspired the name Apple?! As I discovered, “Banana” is her pen name, one she chose for her love of banana flowers!

Returning to ways of representing "path" in kanji, I found 軌跡 (きせき: path one has taken) quite compelling. Whereas 道 (みち) just means "path" and could work in discussions of the past, present, or future, 軌跡 has the past tense built into it. If you’ve left traces (跡) or tracks (軌), they’re inherently in the past.

All of this feels especially appealing to me right now because I've been revisiting the beautiful and hypnotic poem "Traveler, There Is No Road," or Caminante No Hay Camino, by Antonio Machado:

Traveler, your footprints

are the only road, nothing else.

Traveler, there is no road;

you make your own path as you walk.

As you walk, you make your own road,

and when you look back

you see the path

you will never travel again.

Traveler, there is no road;

only a ship's wake on the sea.

Between the Lines

Can you read between the lines of that poem and glean the intended meaning? With Japanese we're constantly having to read between the lines, but it's so hard to know when that's appropriate. I was quite surprised recently when my language partner Kensuke provided this explanation for canceling our talk:

パソコンが壊れて、動かなくなってしまいました。

My PC is unfortunately broken and doesn’t work.

壊れる (こわれる: to be broken); 動く (うごく: to work)

Wasn't this redundant? As Kensuke was literally ill equipped to answer my question, I turned to one proofreader, who confirmed the redundancy but deemed it acceptable. Moreover, he said, between the two clauses lies an implied explanation that Kensuke unsuccessfully tried to fix the machine. The proofreader noted that the Japanese place a high value on an effort to fix things, whether or not the attempt is successful, so people like to indicate that they tried their best. Without such a claim, they may come off badly.

I knew none of this! The last time I read between the lines in Japanese, I thought I detected clever wordplay and was thrilled with my progress. This happened a few weeks ago when I wrote essay 1618 on 逓 (to relay; gradual), which mentions the delivery company 日逓 (にってい: Nittei), short for 日本郵便逓送 (にっぽんゆうびんていそう: Nippon Mail Transportation Co., Ltd.). Several abbreviated names would have been possible. I was certain that someone chose にってい as a pun on 日程 (にってい: schedule). It would be perfect! But, I was informed, no such wordplay exists.

And yet I'm to look between the lines of Kensuke's "broken" and "doesn't work" statements and find a hidden meaning?!

Um, maybe not. A second proofreader detects no such implication in Kensuke's comment!

Grid Shapes

Back when Kensuke was able to use his PC for our chats, he told me about the pressure he feels in Tokyo to wear a mask while running. He used this phrase for the glares he would receive if he were maskless during the COVID era:

白い目で見る (しろいめでみる: to look coldly at; turn a cold shoulder)

white + eye + to look at

What's this? Does a glare make the whites of our eyes more apparent?

No, as I've since learned, the expression comes from The Book of Jin, a Chinese text in which a man named Ruan Ji (210–263) would gaze at those he didn’t respect with 白眼 (はくがん: the whites of one's eyes), otherwise using 青眼 (せいがん: looking at favorably). Yes, the latter term literally translates as "the blue of one's eyes," which is baffling in a Chinese context. Thus, 白眼視 (はくがんし: lit. “looking with the whites of one’s eyes”) means “to look at coldly.” The Japanese usually word this as 白い眼で見る, preferring 眼 to 目 in this set phrase.

Kensuke didn't know this etymology offhand, and it didn't matter, as I was busy gazing at the three kanji in 白い目で見る, admiring the profusion of grid shapes. To express this, I of course had to know how to say "grid shape," and of course didn't. Kensuke produced these possibilities:

升目 (ますめ: (1) square (e.g., of graph paper or genkoyoshi); (2) checkbox (e.g., on a form)) square on a grid + grid

原稿用紙 (げんこうようし: grid paper for compositions)

Oh, right! In essay 1386 on 升 (sho (1.8 liters); small wooden measuring box; square on a grid), I wrote about 升目, as well as these words:

升 (ます: square on a grid)

一升 (ひとます: one square on a grid) 1 + square on a grid

And in essay 1470 on 井 (well; town), I introduced this term, saying that it represents grid patterns in all kinds of designs:

井桁 (いげた: well curb; well lining) well + beam

This word originally described a bird's-eye view of a square well. But because wells are no longer part of daily life in Japan, 井桁 now makes people visualize a grid or lattice pattern.

If a path doesn't keep us sufficiently in line, surely all these little squares will!

❖❖❖

Did you like this post? Express your love by supporting Joy o' Kanji on Patreon:

Comments