Close Encounters of the Tertiary Kind

I always say that every Joy o' Kanji essay is about one character, but that's a lie. After all, kanji are as strongly attracted to one another as people are after downing several drinks on a hot summer night. Kanji bond with other kanji more often than not, so looking closely at one character also means checking out all of its "companions."

I enjoy the secondary discoveries that come with each primary investigation. But I like a tertiary kind of learning even more. That is, by examining sample sentences that showcase the kanji of the moment (and most likely a second kanji), I come upon words I might never otherwise see.

In the case of essay 1823 on 没 (sinking; immersion; disappearing; dying; lack), which came out today, the sample sentences exposed me to three words that were entirely new to me.

For instance, I included this sentence to show 日没 (にちぼつ: sunset) in action:

私達は美しい日没に見とれた。

We admired the beautiful sunset.

私達 (わたしたち: we); 美しい* (うつくしい: beautiful);

見とれる (みとれる: to watch something with fascination)

The verb at the end caught me by surprise. You could say that I watched it in fascination (though it didn't move)! Was the と of みとれる from 取る (とる)? No. The Japanese also read this word as みほれる. Whatever the yomi is, they write the second sound with one of two non-Joyo kanji (when they're not rendering it in hiragana, that is):

見惚れる, where 惚 means "to fall in love with, admire, grow senile"

見蕩れる, where 蕩 means "to melt, be charmed; captivated"

Look at that—love and admiration apparently lead to senility! I didn't realize that. I'll consider this a fourth level of discovery. (I should say "quaternary" to keep with the "primary, secondary, tertiary" theme, but "quaternary" lies a bit outside the range of my vocabulary!)

Photo Credit: Eve Kushner

In Kawabata's Snow Country, I found a lovely compound: 西日 (にしび: afternoon, evening sun), which breaks down as western + sun. He used it in this sentence:

西日に光る遠い川を女はじっと眺めていた。

The woman gazed at the far-off river as it glowed under the evening sun.

光る (ひかる: to shine); 遠い (とおい: distant); 川 (かわ: river); 女 (おんな: woman); じっと (fixedly); 眺める (ながめる: to gaze at)

By the way, the photo above has nothing to do with Kawabata or any snowy region! It's of San Francisco and the Golden Gate Bridge.

Returning to 日没, we can tack on 後 (after) to produce 日没後 (にちぼつご: after sunset), which appears in this sentence:

村は日没後静まり返っていた。

The village was dead after sunset.

村 (むら: village);

静まり返る (しずまりかえる: to become as still as death)

What an intriguing word at the end. (For some reason, the unknown terms do keep coming at the end!) It makes sense that becoming as still as death involves 静, which we know from 静か (しずか: quiet). But 返る (かえる) means "to return." This makes me wonder whether "quiet as death" is the default state to which things can return. Or is it that death itself is the starting and ending point in this scenario?

No, the real explanation is that 返る means "(to become) extremely" when it follows the -ます stem of a verb. And although I associate 静 with the adjective 静か, the word 静まり返る starts with the verb 静まる (しずまる: to quiet down, die down, subside). So 静まり返る is "to die down completely."

Now I've learned not only 静まり返る but also 静まる and a new aspect of 返る. Are these still close encounters of the tertiary kind, or am I up to more like the "quinary" (fifth) or "senary" (sixth) level? I've lost count!

A final sample sentence showcases 没収する (ぼっしゅうする: to confiscate) in its passive form (to be confiscated):

休み中に置き勉してると没収されるんだよな。

If you leave your textbooks at school during the break, they'll get confiscated.

休み中 (やすみちゅう: on break); 置き勉 (おきべん: leaving all your textbooks, etc., at school)

What a highly specific word we find at the end (yes, the end, always the end, as Gotye puts it)! And what a harsh punishment the school metes out to people who leave their books. I suppose the administration really wants students to study over the break!

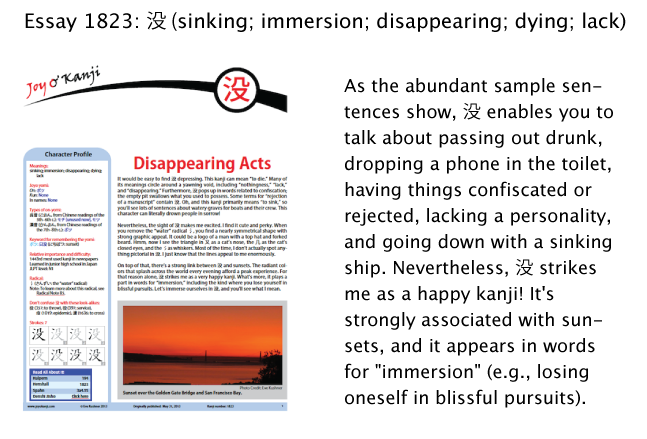

Here's a preview of the new essay 1823 on 没:

Have a great weekend!

Comments