Doubletakes

Last week someone wrote to me and mentioned chai, by which she meant "living" in Hebrew. I grew up in a Jewish environment, and chai may have meant that to me long ago, but now it makes me think of just one thing: milky black tea with a hint of cardamom! Mmm! That's the stuff of my fantasies! I found it impossible to look at the chai she wrote and to think of the word she intended.

In the kanji world, one often does these sorts of doubletakes. Take, for instance, this sentence:

何人ですか。

It looks as if it couldn't be simpler, but that's not entirely true. There are two possible yomi, each with different meanings.

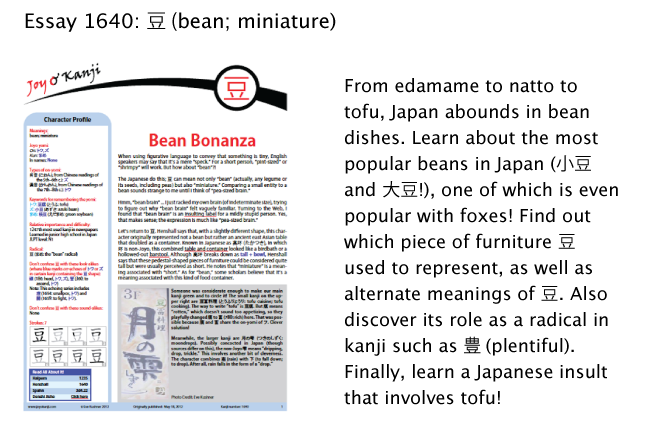

Let's do this as a quiz! See if you can figure out the multiple yomi and meanings. I'll block the answer with a preview of essay 1640 on 豆, which came out today:

Okay, now for the answers about 何人ですか:

If you read it as なんにんですか, you're asking how many people there are.

If you read it as なにじんですか, you're asking about someone's nationality.

That is, the yomi of both 何 and 人 change, as does the meaning of the sentence. Tricky!

When it comes to 人, the Japanese mainly read it as ニン when counting people but as ジン when referring to somebody's nationality, ethnicity, tribe, and so on. People are complicated, and so is the person kanji!

Speaking of 人, look at this word:

故人 (こじん: the deceased; old friend)

Those two definitions serve up quite a discrepancy! I wonder if this ever leads to "Who's on first?" types of confusion. I can just imagine:

![]() 森田さんは故人です。

森田さんは故人です。

![]() What?! Morita-san died???

What?! Morita-san died???

![]() No, no, I was just saying that he's an old friend.

No, no, I was just saying that he's an old friend.

Clearly, this conversation requires you to take a leap of faith that these people would be speaking in a mixture of English and Japanese! Actually, make that archaic Japanese, as that's the only context in which someone would have used 故人 to mean "old friend."

Here's another doubletake situation. I recently saw a native speaker stumble over this word:

付着物

He initially read it as つけきもの but hesitated, probably because the yomi didn't conjure up a word he knew. (I also thought he paused because the word would need to be 付け着物 if it involved the kun-yomi of つけ, but that may not have crossed his mind. In written Japanese, the okurigana in nouns often disappears.)

As it turns out, 付着物 has the yomi of ふちゃくぶつ. It means "attached matter; attached substances; accretion; incrustation," referring to a substance that has latched onto an object and that can provide telltale evidence in a legal case. For instance, 付着物 could mean the sand on a man's shoes, sand indicating that after he killed his brother, he visited a beach, probably to dispose of the murder weapon!

I can certainly see why 付着物 would pose problems for a native speaker. After a lifetime of perceiving 着物 as きもの (a kun-kun combination), a Japanese person could find it quite unnatural to switch to the on-yomi, reading 着 as チャク and 物 as ブツ.

In Crazy for Kanji, Exhibit 41, I provided several examples of compounds that you can read in multiple ways, causing the meaning to change. Some of my favorites:

市場

しじょう: stock market (on-on)

いちば: food market (kun-kun)

一寸

いっすん: one inch (on-on)

ちょっと: a little (kun-kun)

月日

つきひ: months and days, time (on-on)

がっぴ: date (on-kun)

Even though I've long been aware of the dual nature of kanji, this Jekyll-and-Hyde aspect will never cease to amaze me. Aside from 付着物, native speakers seem to think nothing of flipping back and forth between yomi. Perhaps for them it's no more of a jolt than it is to move between the Western and traditional Japanese spaces in their houses. But it remains a shock to my brain, almost as if the two hemispheres weren't connected well enough.

I'm just using that image metaphorically. The short circuit may actually lie in some other part of my brain!

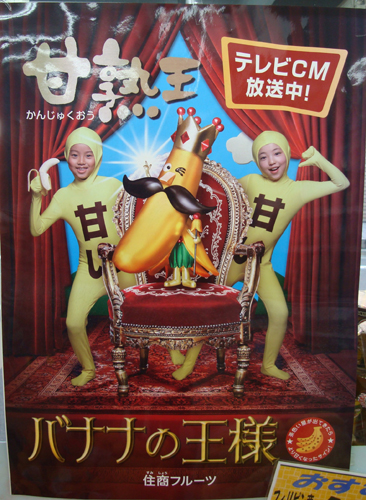

For a final doubletake, check out this photo:

Photo Credit: Kevin Hamilton

I'll explain the text of this ad in my upcoming essay on 甘 (sweet), due out on June 1. For now, just enjoy the visuals. They're even better in this extremely cute video, which worked its way into my head and stayed there for quite awhile!

Have a great weekend!

Comments