Easy Come, Easy Go

Today on Facebook I saw pictures of people I once knew but now can't begin to recognize. For years a woman in that family was my closest friend, but we drifted very far apart, as people do over the decades, and everyone kept on aging, as people also do. I was taken aback by how her relatives had acquired the faces of total strangers.

I mused for awhile about why the photos had made me so uneasy. Was I sad about the loss of that deep friendship? No, we're really no longer well matched. Am I thrown off in a practically cliched way to see that we all get older and that our bodies reflect this? No, that's not it either.

At last I realized that I was despairing at how drastically intimacy levels can fluctuate. And this is true in more relationships than I can count. To think of all that she and I once shared ... To think of how superficial the connection has since become ... I'm sad for a heart that once believed there was something wonderful to hang onto in that relationship, only to learn otherwise.

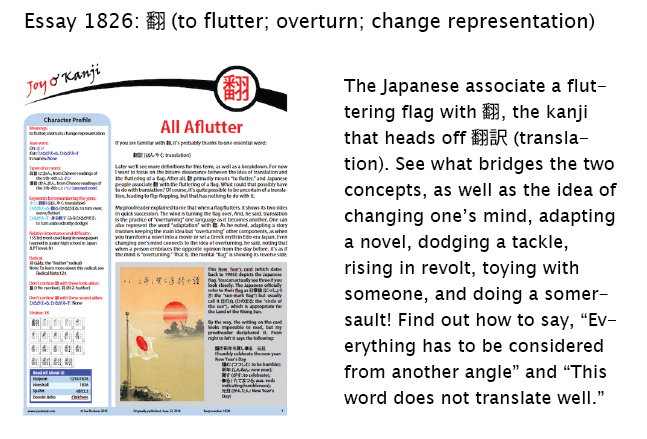

I'm telling you all this because, coincidentally, I keep running into Japanese sayings about the fluctuations of the heart. Take this term from the new essay 1826 on 翻 (to flutter; overturn; change representation):

翻雲覆雨 (ほんうんふくう: instability of human relations)

to turn over + cloud + to turn over + rain

This rare expression comes from an ancient Chinese poem that a source has translated as “Produce clouds with one turn of the hand and rain with another.” The poem likens fickle hearts to a sudden change of weather. Those who were friendly yesterday could become foes today.

I came across the same theme last weekend when I was searching for something in Breen and instead found this uncommon expression:

狡兎死して走狗烹らる

When the enemy is defeated, the victorious soldiers can be killed off.

(Lit., When the nimble rabbit dies, the hunting dog is cooked.)

狡兎 (こうと: nimble rabbit); 死す (しす: to die); 走狗 (そうく: hunting dog);

烹る (にる: to boil, shown here in its passive voice)

Three kanji here are non-Joyo: 兎, 狗, and 烹. Also, 死す is an archaic verb corresponding to the contemporary 死する (しする: to die). Similarly, 烹る, which is more recognizable when written with the synonym and homonym 煮る, is an archaic verb. The contemporary verb is still 煮る, but the passive form has changed over the years from にらる to にられる.

Grammar aside, the hunting dog is cooked?!? What is this all about?

Again this expression is from ancient China, where fickleness seems to have been as rampant as it is now. One site explains the saying by discussing the synonym 狡兎良狗 (こうとりょうく):

重要な地位につき、大きな功績を上げた人も、状況が変わって必要なくなれば捨てられるということ。

A person who has attained an important position and achieved great things can still be thrown away when circumstances change and he becomes unimportant.

重要 (じゅうよう: important); 地位につく (ちいにつく: to attain an important position); 大きな (おおきな: big); 功績を上げる (こうせきをあげる: to succeed); 人 (ひと: person); 状況 (じょうきょう: situation); 変わる (かわる: to change); 必要ない* (ひつようない: unnecessary); 捨てる (すてる: to throw away, shown here in its passive voice)

Wow, no one is safe from fickleness even in the professional realm.

The same source goes on to say this:

兎を取り尽くすと猟犬は必要なくなり、どれだけ役に立っていたとしても、煮て食べられるという意味から。

When the rabbits are all gone (because they have been hunted and killed), the hunting dog becomes unnecessary, and no matter how helpful he has been, he'll be cooked and eaten. The meaning (of the saying) comes from that.

兎 (うさぎ: rabbit); 取り尽くす (とりつくす: to deplete; take all); 猟犬 (りょうけん: hunting dog); どれだけ ... としても (no matter how much); 役に立つ (やくにたつ: to help); 煮る (にる: to boil); 食べる (たべる: to eat, shown here in its passive voice); 意味 (いみ: meaning)

The animals here are just serving a figurative purpose. The ancient Chinese sentence is really about people. That is, when soldiers have defeated an enemy, they become unnecessary and can be killed. In fact, the saying isn't just limited to soldiers. Rather, it extends to practically anyone but those at the top. Competent vassals help their superiors acquire power. Once that has been achieved, the vassals are not only considered unnecessary but are even seen as potential rivals for the top—precisely because of their competence. Thus, they need to be eliminated.

Humans just suck, don't they?

While we're on the subject of fickleness, I also came across this saying recently:

女心と秋の空

Autumn weather is as changeable as a woman's heart.

女心 (おんなごころ: woman's heart); 秋* (あき: autumn); 空* (そら: sky)

Daijisen notes that this saying is specifically about women’s fickle love of men and was originally as follows:

男心と秋の空

Autumn weather is as changeable as a man's heart.

男心 (ことこごころ: man's heart)

Aha! Someone first pinned this on a man!

According to another source, England coincidentally had the same kind of saying: "A woman‘s mind and winter wind change often." In the Meiji era (1868–1912), a Japanese writer introduced this saying to Japan in a novel. Soon afterward, 男心 changed to 女心 in the Japanese version of the proverb.

I would be outraged, but I'm too saturated in my ongoing concerns about the hunting dogs and the rabbits.

The 翻 kanji is rich when it comes to people's changing their hearts and minds, so be sure to check out essay 1826! Here's a sneak preview:

Catch you back here next time!

❖❖❖

Did you like this post? Express your love by supporting Joy o' Kanji on Patreon:

Comments