The Elusive Spirit

Lately I've been craving elusive tastes: malty, smoky, yeasty, earthy ... These flavors are so elusive that I sometimes lack words for them. All the sensations are strong, and yet they somehow slip away quickly. I find myself seeking them in homemade yeasty bread laced with cardamom, in dark and mysterious puer, and in a wonderful smoked tea liqueur that made its way into my cabinet (when and how?!) and that lends an elusiveness to every dish. You'll notice I said "lends." The gift isn't permanent. The flavor vanishes just as soon as the palate wakes up and says, "Hey, what was that?!"

Speaking of yeastiness, I love that the Japanese for "yeast" contains the mother kanji (母):

酵母 (こうぼ: yeast) fermentation + base material

Well, Halpern defines this 母 as "base material," but there's a reason this kanji was chosen to represent that concept here. It's as if yeast brings things to life, much as mothers do.

And there's a great deal of mystery around each creation. I mean, scientifically people understand what happens on a molecular level with both bread and babies, but the way dough rises is still miraculous to me. (I say that with acute disappointment because I made cardamom-date bread last night, and when I awoke this morning and eagerly peered into the machine, I found that the dough hadn't fully risen!)

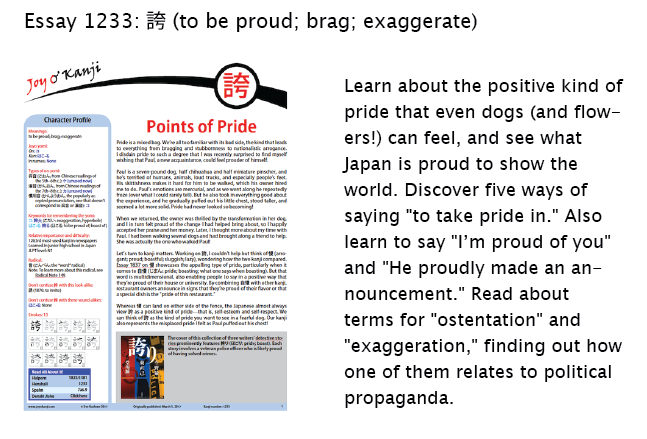

With these themes on my mind, I notice that I'm drawn to two elusive aspects of the new essay 1233 on 誇 (to be proud; brag; exaggerate).

Incidentally, there's nothing subtle about pride, boastfulness, or exaggeration. On the contrary, they take up all the space in the room. It's therefore odd and purely coincidental that the essay brought up the two slippery topics I'm about to mention.

The Spirit of Plants

In writing essay 1233, I learned that plants can swell with pride! Perhaps this happens only in Japan, which is why I never knew this before!

Take, for instance, this term:

咲き誇る (さきほこる: to be in full bloom; blossom in full glory) to bloom + to be proud

From the definitions alone, you wouldn't know that anything here was unusual, but consider the breakdown. The flowers are proud of their blooms, and pride makes them bloom more! Vegetation can have deep feelings!

Despite the depth of feeling here, the intransitive verb 咲き誇る pertains only to literal flowers. English speakers may say that a young woman or an idea is blossoming, but 咲き誇る is strictly floral:

色とりどりのバラが咲き誇る。

Roses of various colors are fully blooming.

色とりどり (いろとりどり: multicolored); バラ (rose)

I found 咲き誇る on a poster in Japan:

Here’s what the largest text says:

幻想的に咲き誇る花たち。

Flowers fantastically in bloom.

幻想的 (げんそうてき: fantastic); 花たち (はなたち: flowers)

The translations convey only a physical description of flowers, so it's very easy to lose sight of the 誇 in these phrases. I feel it's important not to do so because it clues us in to something. To show you more of what I mean, I'll share a translated sentence that I weeded out of the essay at the last minute:

In the bleakness of a garden in winter, cedars and pines stay green.

I cut the sentence after learning that the corresponding Japanese text was so old as to have archaic syntax. In particular, the text incorporated 誇 in a way that no longer works with contemporary grammar.

Even so, I'm glad I came across the sentence because it prompted me to ask a proofreader why the sentence contained 誇. As he explained, the cedars and pines themselves are proud of being green in a bleak garden. He told me that although it may sound strange in English to say that trees can be proud of anything, "It’s quite natural for the Japanese to acknowledge that everything (including rivers, trees, and mountains) has its own spirit or god. Thus, the spirit in these trees is proud of their greenness!"

This blew my mind! And yet, as I'm writing this, I keep looking out the window, seeing the nearby plum tree lose blossoms in the breeze. They float sideways almost unsteadily, and it occurs to me that nature is far from stable. We may think of trees and certainly rocks and rivers as permanent, but in fact nature is quite dynamic, the trees constantly changing their "clothes," the rivers rushing by, and (especially in sodden California lately) the boulders sliding down hills and landing on highways!

I wonder if that rustling in nature inspired the ancient Japanese to believe that spirits or gods inhabit everything. (Or maybe they really do inhabit everything, and Westerners are slow on the draw!)

The Spirit of 気

Matters of the spirit also arose in essay 1233 in a very different way. I often have trouble translating the ultra-common kanji 気. I associate it with "spirit," but that's certainly not always the meaning. After I sent one proofreader a long set of questions about the essay, I noticed that three pertained to that character.

One question involved a sentence featuring 誇らしい (ほこらしい: proud; haughty, arrogant; splendid, magnificent):

彼女の顔は誇らしさで赤く上気していた。

She was flushed with pride.

彼女 (かのじょ: she); 顔 (かお: face); 赤い (あかい: red); 上気 (じょうき: flushing (of one’s cheeks))

I asked two things about this sentence:

1. Why in the world would 上気 mean "flushing (of one’s cheeks)"?

2. If 上気 means what it does, why is 赤く needed here?

He confirmed that the 赤く is redundant, saying that such redundancy is often fine in Japanese sentences.

As for 上気, he consulted his sources and found no definitive answers but offered an intelligent guess: "The 気 part should be the sort of 気 (qi) from Chinese that's loosely about one’s vital energy. When such energy goes up (上) to one’s head, one flushes."

I also inquired about the meaning of 気 in the second rendering of this word:

誇らしげ or 誇らし気 (ほこらしげ: proud; triumphant) proud + atmosphere

He said it means "atmosphere" there. What a change from "qi." And here's an even bigger shift:

気質 (きしつ: character, nature, temperament) one's nature, temperament + quality

He said that this term sounds scientific or medical, originally coming from Hippocrates' "humorism" (an ancient system of medicine) and later becoming a subject of research in psychology.

It seems that 気 is all over the place, elusive in its own special way.

Slipsiding Away

On the topic of slipperiness, I've been spending time with a friend who overflows with creativity. His brainstorming is something to behold. And I notice how even when he's not tackling a problem, his mind slipslides from association to association. He can be unsure whether it snowed the day before or whether he only dreamed it. And he's unclear about directions, telling me he lives at the bottom of a hill when he actually lives at the top! This loose relationship between thoughts must be precisely what fuels his creative brilliance.

Achieving more mental looseness may help us all right now as we pass through a horribly unstable time. What looked like solid ground is revealing itself to be quicksand. The changes are happening faster than anyone can comprehend. That's also true in my personal life.

It feels wrong, all this change. Just plain wrong. In my mind, the future wasn't supposed to be significantly different from the past. I made big plans based on that assumption. We probably all make plans based on our understanding of the past. No wonder plans are often foiled. The past is the source of our knowledge but is by definition outdated and therefore sometimes irrelevant.

With all this uncertainty, it helps to think that nature is constantly in flux, as is life, all of us mortals cycling through birth and death on individual schedules. Life is change, and living is about trying to catch up to those changes. This is inherently impossible because just as soon as one grasps a new state of affairs, they've changed again!

Perhaps kanji represent and reflect this flummoxing flux better than anything I know. One minute, 気 is qi that causes cheeks to redden. Another minute, 気 is the atmosphere or part of a scientific term. Most of the time, 気 is キ, but sometimes it's ケ or いき.

I love this quality in kanji much more than in life!

Onward

Enough philosophizing. Here's a preview of the newest essay:

Joy o' Kanji is off next week for spring break! I'll be back with you in mid-March!

Comments