How Complicated Was My Valley

My life lately has been about translation quagmires!

Last week, two JOK documents coincidentally included 悔. I had great trouble making sense of this kanji because my proofreaders said they associated 悔しい (くやしい) with a wide range of feelings—everything from anger and vexation to sadness to mortification, regret, repentance, and frustration! Both native speakers also explained that there is no English equivalent.

The proofreader who goes by Lutlam online illustrated the idea of 悔しい this way: "Suppose you find out an important truth about kanji and want to write a book on it, only to learn that somebody else has beaten you to it. The feeling you have then is 悔しい. It's what you feel when things don't turn out as you hoped and there's nothing you can do about it." Ah, that helps.

When the Japanese hear 悔しい, he said, they need to figure out the best meaning from the context. The interpretation also depends on whether the 悔しい is about a situation or about a feeling.

After extensive discussions with him and the other proofreader, I finally settled on "chagrin, regret, humiliation, vexation, bitterness" as the primary definitions of 悔. That's one powerful kanji—and a complex set of emotions!

Well, psychology is just about as complicated as culture, so it makes sense that we would run into obstacles of this nature. But I didn't expect any kind of tumult when it came to nature itself! Isn't an apple an apple and a waterfall a waterfall all around the world?

No, as I've seen with the recent to-do over various definitions, it's probably best not to hope for one-to-one correspondences or easy equivalencies, no matter how straightforward the subject may seem. After all, if you go into any kanji situation anticipating a smooth ride, you're just setting yourself up for some big bumps!

A Plum Job for Translators

In particular, Japanese fruit has posed considerable problems.

This week we struggled with a dead ringer for 悔—namely, 梅 (うめ), which one often hears translated as "plum." Wrong! Lutlam's sources unanimously define "plum" as セイヨウスモモ (西洋酸桃) or プラム. Only one of his dictionaries says that the term can colloquially refer to 梅. The "right" answer is to define 梅 as "Japanese apricot."

Plums also came up in the forthcoming essay 2063 on 旦 (dawn, daybreak, morning; first day). There I wrote that 巴旦杏 (はたんきょう), in which only 旦 is a Joyo kanji, can mean both "plum" and "almond." I figured that the Japanese avoid potential confusion by using synonyms, and I was right and wrong. They do indeed use synonyms. For "almond," アーモンド works. And for "plum"? Of course my mind kept going back to 梅, but no! Wrong species! Instead, the Japanese refer to the plummy kind of 巴旦杏 as スモモ, which corresponds to 酸桃 or 李, in which the last kanji is non-Joyo.

Of Valleys and Basins

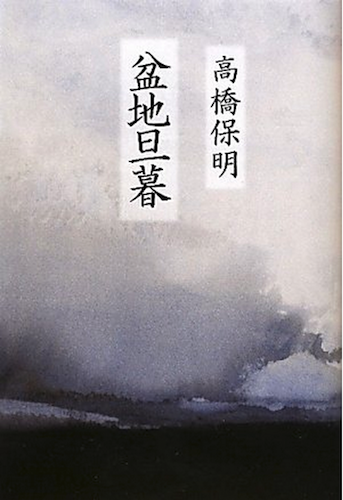

Essay 2063 also precipitated a lengthy discussion about 盆地 (ぼんち), which appeared in a book title. Breen defines 盆地 as "basin (between mountains)." I didn't see how that would be different from a valley, so I changed it in the title translation.

Lutlam disagreed, saying that "valley" usually translates as 谷 (たに), which the Japanese distinguish from 盆地. He quoted two Japanese-Japanese dictionaries on the matter, noting that both define 盆地 as "(low), flat land surrounded by mountains." He pointed out the use of 平地 (へいち: level ground; plain) in the Daijisen explanation and 低平 (ていへい: low and flat) in Daijirin, concluding that flatness is particularly important.

Then he turned to English-English sources for "valley" versus "basin." Collins COBUILD Dictionary provides these definitions:

"A valley is a low stretch of land between hills, especially one that has a river flowing through it."

"In geography, a basin is a particular region of the world where the earth's surface is lower than in other places."

He decided that the two entities differ in the existence of a river. Ultimately, he said, "basin" sounds much closer to what the Japanese perceive as 盆地. And he mentioned that the southern part of Kyoto Prefecture is called 京都盆地 (きょうとぼんち), "which is obviously too flat and large to be called a 谷 or valley." To give me an idea of its size, he included this Wikipedia photo of the place:

He added that the 盆 in 盆地 means "tray," noting that it's logical that land shaped like a tray would be flat.

Despite all this, I couldn't see using "basin" in the translation of a book title that was supposed to be poetic. Just look at the mood the cover sets:

On top of that, I realized that English speakers must use "valley" in a much looser way compared with the Japanese and 谷. After all, a huge chunk of California is known as the Central Valley, and it's 60 to 100 kilometers wide.

So I went with The Valley at Dawn and Dusk as the title translation but defined 盆地 more precisely in the vocabulary listing underneath, explaining it as "stretch of low, flat land between mountains." I included no basins anywhere. They make me think of bathrooms!

Various Fields Forever

Yet another issue of this type arose in email correspondence between Mark Spahn and his friend. Spahn, coauthor with Wolfgang Hadamitzky of The Kanji Dictionary, rightly sensed that I would be interested in the discussion and copied me on the exchanges.

The first one concerned the phrase 桑原桑原 (くわばらくわばら), which combines 桑 (mulberry) with 原 (field). One might translate the phrase in any of these ways: "Heaven forbid!" "Thank God!" "Knock on wood!" "Keep your fingers crossed!"

Spahn observed, "The fact that these four translations have nothing in common hints that this is an all-purpose emotional interjection. Whether it is to be taken literally as 'mulberry-tree field' (if it’s full of trees, how can it be a field?) or as a surname Kuwabara, I don’t know."

That wasn't the end of the matter, of course. He consulted Shin MeiKai Kokugo Jiten, a Japanese-Japanese dictionary, and translated its 桑原 entry this way: "A saying that lightning (disaster) doesn’t strike where mulberry trees (food for silkworms) grow." To Spahn, that finding explained the “Knock on wood!” translation, as that's another expression for averting catastrophe.

But, he mused, "I still don’t understand why a mulberry-tree orchard should be a 原, which I take to mean a treeless piece of agricultural land."

"Hey," he concluded, "didn’t the Beatles write a song called「桑原万歳!」? Yeah, they did." He supplied a YouTube link.

Of course, the Beatles didn't include 万歳 (ばんざい: hurrah; 10,000 years; forever) in their title—or 桑原, for that matter!

I wrote back with a gleaning from essay 1020 on 悦 (delight, pleasure, happiness, joy) where I had mentioned Miho Pine Fields (三保の松原, みほのまつばら) in Shizuoka Prefecture. "So it's not just mulberry trees that form fields. Apparently, pines do, too," I said.

He promptly resumed the investigation: "My question is about the English language. Do we use the word 'field' for any place where trees grow? If trees are planted for an agricultural reason, in serried ranks of precisely positioned rows and columns, I think we call it an (apple) 'orchard' or maybe an (orange) 'grove,' not a 'field.'”

He then undertook online searches for apple fields, pine fields, and mulberry fields, gradually realizing that the height of a mature mulberry might be a key issue: "Those mulberry trees look no taller than corn. We speak of 'cornfields,' so maybe 'field' includes plants that don’t grow very tall. Hey, how tall does a mulberry tree grow? If no taller than a stalk of corn, then 'mulberry field' would be just as justified as 'cornfield.'"

I very much liked this train of thought, but the theory didn't pan out because, as he found, the most commercial mulberry is the white mulberry, which grows as high as 20 meters—far taller than an apple tree.

He tentatively concluded that 原 (はら) and 畑 (はたけ: field) have broader meanings than the English “field," which a dictionary defines primarily as “a wide stretch of open land; plain" or "a piece of cleared land, set off or enclosed, for raising crops or pasturing livestock." Both definitions indicate treelessness to him.

Ah, and that discussion reminds me of another I just had with Lutlam. I was trying to come up with the primary definitions of 田 and wondered if "rice field, field" would do the trick.

No, it wouldn't. This answer came back: "By 'field,' do you mean that of other produce, like carrots or corn?" If so, he said, that had to be 畑. Then again, 油田 (ゆでん) means "oilfield," so "field" does work in that sense.

We ended up with this listing for 田: "rice field; (oil, coal, etc.) field; 'rice field' radical."

And so it goes, from one field to another. I suddenly understand the meaning of the title "Strawberry Fields Forever." The Beatles must have meant that when you embark on such discussions, they're bound to last forever!

Be sure to check out the newly posted essay 2081 on 頓. Here's a sneak preview:

Have a great weekend!

Spahn: Your discussion of 桃 and 酸桃 reminds me of the saying「酸桃も桃も桃のうち。」= Both plums and peaches are in the peach family. Notice here that you get eight も’s in a row.

And here’s one with lots of “oh”s in a row: ローマ法王を往々応援する = frequently supporting the pope.

Hadamitzky noted that you can also write the first saying this way: 李も桃も桃の類. My proofreader thinks that that version is less common, also noting that he's never heard the pope line in his life.