Jay Rubin and "The Sun Gods": A Guest Blog

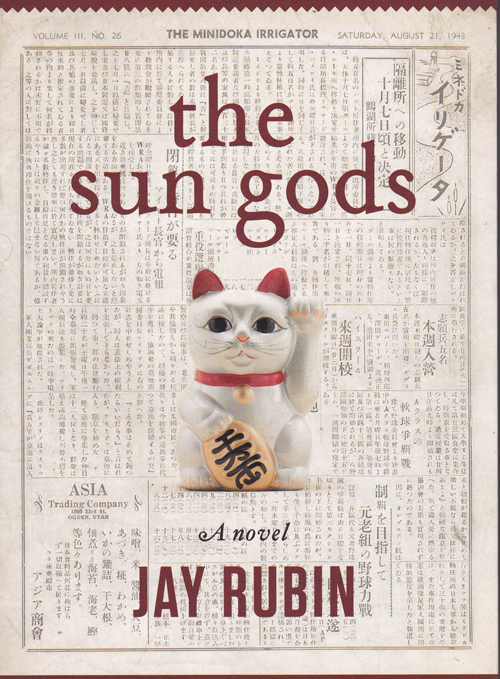

Last week I attended a reading in San Francisco by Jay Rubin, who has just come out with the novel The Sun Gods. You may know him as the translator who has made it possible for many of us to fall in love with Haruki Murakami, and Rubin is indeed that person, but he's also so much more.

I had looked forward to this event for six weeks, arranging my schedule so that I'd be working on the ultra-short essay 2103 on 阜 (hill, mound; “left hill” radical) right about then, leaving me extra time that I usually don't have. Despite all my happy anticipation, I wasn't the least bit disappointed. (How often can one say that?!) On the contrary, the reading exceeded anything I could have imagined because I had a chance to chat with Rubin afterward as he signed three books for me, two of which have meant a great deal in my life.

It was only afterward that I realized how long I'd been needing to talk to him.

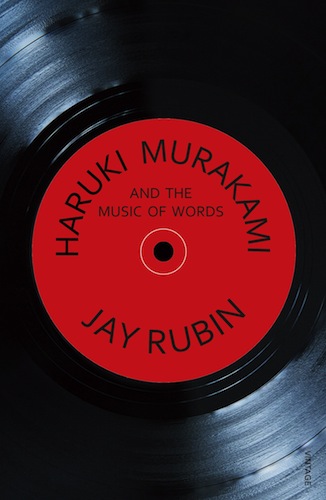

I'm not quite sure when I became aware of Rubin, but all the way back in 2002 I bought his nonfiction work Haruki Murakami and the Music of Words at Maruzen, a Tokyo bookstore, and read it intently on the flight home, making copious margin notes.

"I sense a project coming on!" said my husband with amusement from the next seat.

He was right in a sense. I felt as drawn to the material (and as eager to interact with it) as if I were about to do something huge with it, but I didn't have the slightest idea what that something would be. (That is, in fact, how I felt during my early years of kanji study, and in no time kanji became the center of my life!)

I think my experience was quite natural, given that Rubin's accessible, conversational writing stimulated thought after thought in me. I had the same experience at his reading; questions cascaded through my mind, and I had to exercise self-control so that I didn't dominate the Q&A session with everything I wanted to ask.

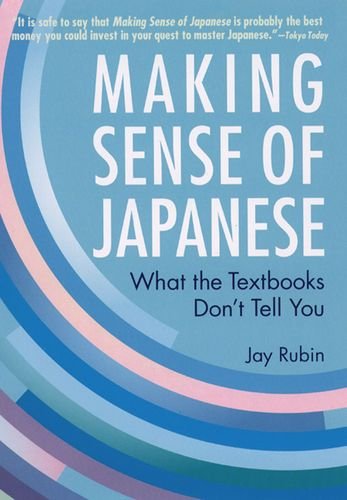

Then, as we chatted one on one, I was able to share a bit about what I'd gotten out of his books, including Making Sense of Japanese: What the Textbooks Don't Tell You, in which one of the highlights is Rubin's advice on how to approach extremely long, tangled sentences. No longer was I having a one-sided conversation with the margin of his books. He could actually hear me and respond, and I felt amazingly gratified.

Of all the gifts he has given his readers, perhaps the most valuable is that he demystifies a language and a thought process that people (native speakers and learners alike) are all too willing to shroud in dense layers of "You'll never understand if you're not Japanese."

Take, for instance, this passage from Haruki Murakami and the Music of Words: "The Japanese language is so different from English—even when used by a writer as Americanized as Murakami—that true literal translation is impossible, and the translator's subjective processing is inevitably going to play a large part. That processing is a good thing; it involves a continual critical questioning of the meaning of the text. The last thing you want is a translator who believes he or she is a totally passive medium for transferring one set of grammatical structures into another: then you're going to get mindless garbage, not literature" (p. 286).

With such passages, Rubin deftly dissolves the barrier between himself and the reader. And that's why I can't get enough of his writing, which is consistently grounded, friendly, and playful. As I read I think, "Yes, this is where I want to be. These are the thoughts I want to be having. This is the voice I want in my head right now."

Although Rubin has every right to put on airs, given his lengthy list of achievements and excellent work, he was downright self-effacing at his big event, promoting four other people's books instead of focusing on his own. He seemed to think the audience might prefer to hear about Murakami rather than the novel Rubin has just published. How many writers would do that?

Well, I for one would like to hear much more from Rubin himself, so I invited him to write about his new novel from a kanji perspective. He swiftly produced the following piece, which I'm delighted to share with you.

❖❖❖

The Sun Gods is a melodrama set in a very specific time and place: Seattle during World War II, when all people of Japanese ancestry, citizens and noncitizens alike, were forcibly removed from the West Coast and sent to so-called relocation camps, which were nothing so much as America's own concentration camps. The book focuses on the racism and hypocrisy behind these developments as played out in the lives of a small cast of characters. Much of the energy I poured into the novel went toward making the historical setting as accurate as possible, but there were also language issues to deal with, including at least one involving kanji. In a scene on page 94, the heroine Mitsuko's white husband, Tom, has begun to show his impatience with her Japaneseness:

“We have to work on making you more American,” he said, his voice softening. “You can’t apply for citizenship yet. Maybe we can start with your name.”

“What do you mean?”

“We can change your name,” he said, “or give you a new one.”

“I do not want to change my name.”

“Why not? What’s so special about it? You’re always complaining that Americans never pronounce it correctly. Does it mean something?”

“Not exactly. Mitsu is hikaru—to shine.”

“What do you mean, ‘Mitsu is hikaru’? Mitsu is Mitsu.”

“It is very difficult to explain.”

Mitsuko does not try to explain to Tom how Mitsu could possibly be something as different-sounding as hikaru. She would have had to explain to him the whole Japanese writing system with its odd combination of Chinese characters and Japanese phonetic symbols; she would have had to show him how 光 could be pronounced Mitsu in her name, 光子 (Mitsuko), when combined with 子, the common "child" ending of feminine given names; and she would have had to explain to him how the particular Mitsu in her name could be differentiated in Japanese conversation from other kanji pronounced Mitsu that might have been used to write Mitsuko (for example, 美津 or 充 or 美都). She instinctively says what any Japanese speaker would say under the circumstances, "Mitsu is hikaru," pronouncing the verb written with her Mitsu character, 光る (ひかる: to shine).

It's the easiest thing in the world for those who know kanji, and a hopeless task in the context of strained marital relations, so Mitsuko leaves Tom clueless, an experience shared by the uninitiated reader.

By the way, JOK readers might be interested to know that when the Japanese translation of the novel comes out from 新潮社 (しんちょうしゃ) next month, 光 will appear—as the noun ひかり—in the title 「日々の光 (ひびのひかり)」. Don't ask why the title is not a more literal translation of the English original. That would require a whole new explanation that has nothing to do with kanji.

❖❖❖

By the way, this is the cover of Jay Rubin's book on Murakami:

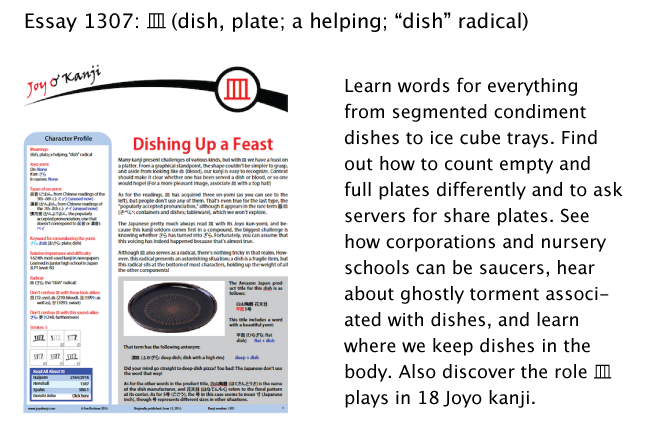

As it happens, I learned by writing the new essay on 皿 (dish, plate; a helping; “dish” radical) that the Japanese use 皿 colloquially when referring to the kind of record that goes on a record player. In fact, I came across a record-shaped dish, which is to say an お皿-shaped お皿!

Here's a sneak preview of essay 1307:

Have a great weekend!

Comments