Joy and Art from Pain

A few weeks ago, I posted something on Facebook about Soseki's novelгҖҢиҚүжһ• (гҒҸгҒ•гҒҫгҒҸгӮү: Kusamakura)гҖҚ, and a Japanese friend responded by sharing a photo of this book, which he adores:

Photo Credit: Naohiko Nishihata

He also copied the opening lines of the novel:

еұұи·ҜгӮ’зҷ»гӮҠгҒӘгҒҢгӮүгҖҒгҒ“гҒҶиҖғгҒҲгҒҹгҖӮ

жҷәгҒ«еғҚгҒ‘гҒ°и§’гҒҢз«ӢгҒӨгҖӮжғ…гҒ«жЈ№гҒ•гҒӣгҒ°жөҒгҒ•гӮҢгӮӢгҖӮж„Ҹең°гӮ’йҖҡгҒӣгҒ°зӘ®еұҲгҒ гҖӮгҒЁгҒӢгҒҸгҒ«дәәгҒ®дё–гҒҜдҪҸгҒҝгҒ«гҒҸгҒ„гҖӮ

дҪҸгҒҝгҒ«гҒҸгҒ•гҒҢй«ҳгҒҳгӮӢгҒЁгҖҒе®үгҒ„жүҖгҒёеј•гҒҚи¶ҠгҒ—гҒҹгҒҸгҒӘгӮӢгҖӮгҒ©гҒ“гҒёи¶ҠгҒ—гҒҰгӮӮдҪҸгҒҝгҒ«гҒҸгҒ„гҒЁжӮҹгҒЈгҒҹжҷӮгҖҒи©©гҒҢз”ҹгӮҢгҒҰгҖҒз”»гҒҢеҮәжқҘгӮӢгҖӮ

I'll come back to the reddened words.

Here's the corresponding translation by Meredith McKinney:

As I climb the mountain path, I ponder—

If you work by reason, you grow rough-edged; if you choose to dip your oar into sentiment's stream, it will sweep you away. Demanding your own way only serves to constrain you. However you look at it, the human world is not an easy place to live.

And when its difficulties intensify, you find yourself longing to leave that world and dwell in some easier one—and then, when you understand at last that difficulties will dog you wherever you may live, this is when poetry and art are born.

Amid all that pain, Soseki included bits of joy (no doubt inadvertently). I find some, for instance, in this term:

и§’гҒҢз«ӢгҒӨ (гҒӢгҒ©гҒҢгҒҹгҒӨ: to cause needless offense and worsen a relationship)

edge + to be at a right angle

McKinney translated this as "you grow rough-edged," apparently highlighting the meaning of и§’ here. As for з«ӢгҒӨ, the idea is that the edge is butting up against something else at a right angle, the position in which the edge does the most harm. This sounds rather like "being at odds" with someone.

We see и§’ again in the next word:

е…Һи§’ (гҒЁгҒӢгҒҸ: something impossible) rabbit + antlers

However, the yomi of и§’ has changed from гҒӢгҒ© to гҒӢгҒҸ, and the meaning has shifted from "edge" to "antlers." Although Soseki's original version has гҒЁгҒӢгҒҸ in hiragana, my friend typed out the passage with е…Һи§’, which got me thinking. The non-Joyo е…Һ means "rabbit." Antlers on a rabbit are impossible, so е…Һи§’ represents that impossibility! That sense infuses the bit that McKinney translated as "However you look at it, the human world is not an easy place to live."

Incidentally, the same term can have a separate set of unrelated meanings:

е…Һи§’ (гҒЁгҒӢгҒҸ: (1) (doing) various things; (doing) this and that; (2) being apt to; being prone to; tending to become; (3) somehow or other; anyhow; anyway)

This word is ateji; the meanings of the two kanji cease to matter here. Dictionaries say that this term consists of two adverbs: гҒЁ (as such) + гҒӢгҒҸ (as such). Those sounds also combine in variations such as гҒЁгҒ«гҒӢгҒҸ, гҒЁгӮӮгҒӢгҒҸ, and гҒЁгҒ«гӮӮгҒӢгҒҸгҒ«гӮӮ, all of which mean the same thing as the latter гҒЁгҒӢгҒҸ (with extremely subtle differences in the nuances).

We've come some distance from the last paragraph in Soseki's passage, so here it is again, along with the translation:

дҪҸгҒҝгҒ«гҒҸгҒ•гҒҢй«ҳгҒҳгӮӢгҒЁгҖҒе®үгҒ„жүҖгҒёеј•гҒҚи¶ҠгҒ—гҒҹгҒҸгҒӘгӮӢгҖӮгҒ©гҒ“гҒёи¶ҠгҒ—гҒҰгӮӮдҪҸгҒҝгҒ«гҒҸгҒ„гҒЁжӮҹгҒЈгҒҹжҷӮгҖҒи©©гҒҢз”ҹгӮҢгҒҰгҖҒз”»гҒҢеҮәжқҘгӮӢгҖӮ

And when its difficulties intensify, you find yourself longing to leave that world and dwell in some easier one—and then, when you understand at last that difficulties will dog you wherever you may live, this is when poetry and art are born.

I love how the look-alikes жҷӮ (when) and и©© (poetry) are back to back!

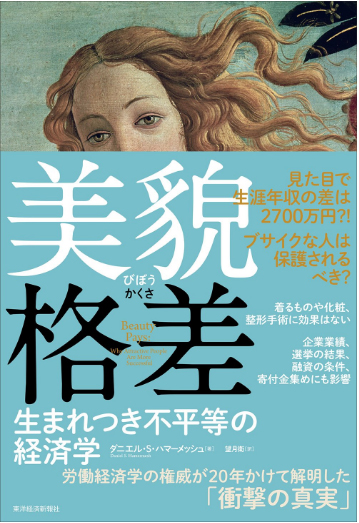

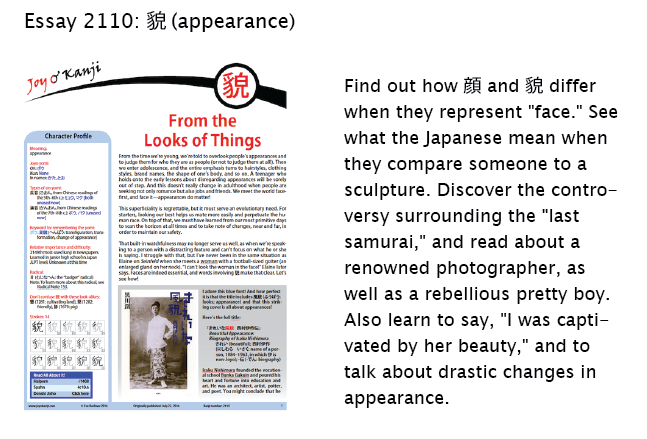

As for the з”ҹгӮҢгҒҰ, referring here to the birth of poetry and art, I recently learned something about з”ҹгҒҫгӮҢгӮӢ (гҒҶгҒҫгӮҢгӮӢ: to be born), part of which pops up on a book cover in the newly published essay 2110 on иІҢ (appearance):

Here's the title:

гҖҢзҫҺиІҢж је·® з”ҹгҒҫгӮҢгҒӨгҒҚдёҚе№ізӯүгҒ®зөҢжёҲеӯҰгҖҚ

The Beautiful Face Disparity: Economic Inequality Depends on How You're Born

зҫҺиІҢ (гҒігҒјгҒҶ: beautiful face); ж је·® (гҒӢгҒҸгҒ•: disparity); дёҚе№ізӯү* (гҒөгҒігӮҮгҒҶгҒ©гҒҶ: inequality); зөҢжёҲеӯҰ (гҒ‘гҒ„гҒ–гҒ„гҒҢгҒҸ: economics)

The red part is one word and means “to be born that way.” Here are other examples:

з”ҹгҒҫгӮҢгҒӨгҒҚзӣ®гҒҢиҰӢгҒҲгҒӘгҒ„

born blind

зӣ®гҒҢиҰӢгҒҲгӮӢ (гӮҒгҒҢгҒҝгҒҲгӮӢ: to be able to see)

з”ҹгҒҫгӮҢгҒӨгҒҚдёҚе№ізӯү

born unequal

Let's go back to Soseki and the part about how pain produces art. I saw something ever-so-slightly related in this month's issue of The Sun, which contains an excerpt from We've Had a Hundred Years of Psychotherapy—And the World's Getting Worse by James Hillman and Michael Ventura. The quoted passage includes this observation:

Wounds and scars are the stuff of character. The word character means, at root, "marked or etched with sharp lines," like initiation cuts.

The comment is about people's characters, of course, but it makes me think of Chinese characters, often engraved in wooden signs, pottery, and elsewhere. Maybe just maybe, the more pain we experience in life, the more Chinese characters we'll have etched into our brains! Wouldn't that be nice?!

Here's a preview of the newest essay:

Have a great weekend!

Comments