Numbers That Don't Count

This is the time of year to think about numbers. Last weekend, some people took note of the time 10:11 on 12/13/14. Others are counting down the days till Christmas or vacation. Soon we'll need to remember to write 2015, not 2014. I should at least be comfortable with writing 2014 by now, but when I recently had to indicate the year on a document, I started with "19"! I then paused to think about where we are in time and whether I had spaced out on the last 15 or so years!

Some numbers matter a great deal. For instance, this week I completed the 150th JOK essay! It always feels great to reach those milestones.

On the flip side, I've encountered some Japanese expressions in which the numbers simply don't count.

Take this sentence, which came to me in an email from a friend:

勿論教材以上の内容であることは百も承知です。

Of course I'm fully aware that the content is more than teaching material.

勿論 (もちろん: of course); 教材 (きょうざい: teaching material); 以上 (いじょう: more than); 内容 (ないよう: content)

The red term has the following idiomatic meaning:

百も承知 (ひゃくもしょうち: knowing only too well; being fully aware of)

100 + awareness (last 2 kanji)

What, I wondered, was the origin of this expression? A hundred what?

I consulted my proofreader, who said that the 百 here has nothing to do with the actual number 100. Rather, because 100 of anything is a lot, this 百 simply means "very much" or "well."

He cited a similar example:

千万 (せんばん: exceedingly; very many; very much; indeed) 1,000 + 10,000

Note that whereas the yomi of the actual number 千万 is せんまん, the reading changes to せんばん when the numbers don't count.

This term serves as the suffix to the next:

失礼千万 (しつれいせんばん: extremely rude)

rude (1st 2 kanji) + exceedingly (last 2 kanji)

Wait, something seems familiar.... Aha, I talked about the same suffix in essay 1727 on 卑 (base, lowly, vile, vulgar, mean) regarding this word:

卑怯千万 (ひきょうせんばん: sneaky; extremely unsportsmanlike)

cowardice (1st 2 kanji) + 1,000 + 10,000

I also included 千万 in essay 1113 on 憾 (to regret strongly; be sorry; be dissatisfied), which contained this yojijukugo:

遺憾千万 (いかんせんばん: highly regrettable; utterly deplorable)

regrettable (1st 2 kanji) + very much (last 2 kanji)

I said there that according to one site, this kind of 千万 is akin to “a million” in “Thanks a million.”

To expand on the discussion, I provided this sample sentence:

君がそれを知らないのは遺憾千万だ。

It is a great pity that you don’t know it.

君 (きみ: you); 知る (しる: to know)

So 百も承知 is associated with knowing all too well, and 遺憾千万 appears in a sentence about not knowing enough!

As long as we're talking about yojijukugo with numbers, here's one that my language partner mentioned after I described the mammoth storm that laid waste to the San Francisco area last week:

台風一過 (たいふういっか: clear weather after a typhoon has passed)

typhoon (1st 2 kanji) + passing away (last 2 kanji)

I zeroed in on the 一 at its center. One what?

Dictionaries say that 一過 (いっか) means "to pass in a short period of time." Furthermore, the 一 in 台風一過 simply indicates that the typhoon left in a flash. This kanji has nothing to do with the number one.

Did you already guess that? Then a high-five to you!

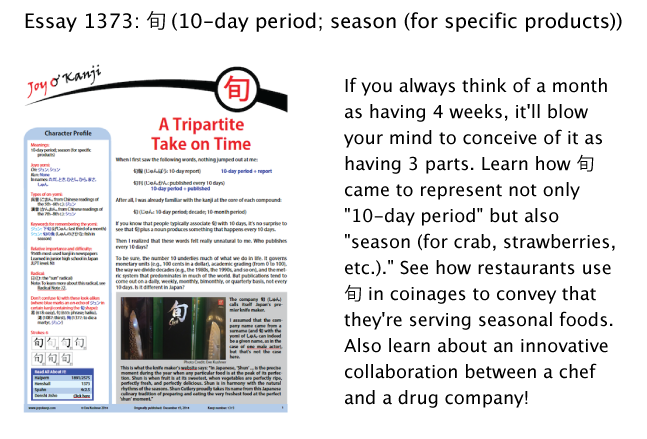

Numbers also play an important role in the newest essay, which is on 旬:

Because 旬 primarily means "one third of a month," the number three comes up a lot in the essay. But that's not quite what I mean when I say that numbers factor heavily into that essay. As I explain there, conceiving of a month with a tripartite structure is quite exciting to me. It brings back a time in seventh grade when our math teacher showed us how to understand the world with an alternate framework. It blew my mind to learn that although we’ve organized many systems around 10s (as with the 10s column and the 100s column in numbers such as 560), it doesn’t have to be that way. It’s just one option. You can express any number with a base-2 system or a base-3 system and so on. Using 10 is simply a common standard that we’ve all adopted for ease of communication.

This shook me up in the most wonderful of ways. What else had I taken to be inevitable or “the only way” when in fact they were just choices or conventions? Perhaps thinking of time in terms of 旬 holds the same promise!

Speaking of time, this is it for a few weeks, as JOK will be on vacation. The next essay (on 忙, "busy, occupied; restless") will appear on January 9. Around that time I'll post Radical Note 123 on 羊, the "sheep" radical, to usher in the Year of the Sheep! I wish you all the best for the holidays and the new year!

Comments