One and Not the Same

Do you think of 一 (one) as representing a lot or a little? This isn't necessarily a question about Japanese; when English speakers refer to coming together as one, it conveys that many people have united. On the other hand, as Aimee Mann says, one is the loneliest number that you'll ever do.

I've encountered a few 一 terms that threw me off. One popped up in the forthcoming essay 1848 on 滅 (to destroy; annihilate; cease to exist; ruin) in this sample sentence for 滅茶滅茶 (めちゃめちゃ: (1) disorderly; messy; ruined; (2) absurd; unreasonable; excessive; rash):

一体だれが私の名簿を滅茶滅茶にしたのだ。

Who in the world has gone and messed up my list of names?

I knew 私* (わたし: I), of course, and I could easily locate 名簿 (めいぼ: list of names) in the dictionary. But what in the world was going on with that blue term?

Here's what I learned it could mean:

一体 (いったい: (1) (before an interrogative, forms an emphatic question) ... the heck (e.g., "what the heck?"); ... in the world (e.g., "why in the world?"); ... on earth (e.g., "who on earth?"); (2) 1 object; 1 body; unity; (3) 1 form; 1 style; (4) 1 Buddhist image (or carving, etc.)) 1 + body

Clearly, the first definition applies—and what a great definition it is! It appears that only the second definitions match the breakdown, so where in the heck did the initial meanings come from? Who on earth knows? But I'm happy to see that our kanji 一 conveys a sense of singularity at least some of the time.

If you tack on に, the meaning changes significantly:

一体に (いったいに: generally; in general)

This turns out to be quite a rare and old-fashioned term. Still, it's of interest because with the addition of に, we go from just one of something (one object, which is a small amount) to most of something (the majority). That is, with "generally," we have the large kind of "one," as when we all pull together as a team. (Now I'm channeling Pink Floyd instead of Aimee Mann.)

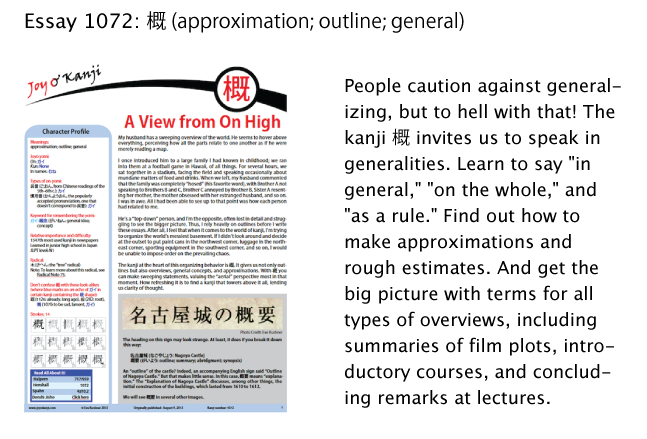

It's funny that I should run into a term for "generally" because that's what the newly published essay 1072 on 概 (approximation; outline; general) generally covers!

I'm happy to have a handle on the complicated-looking 概, but let's go back to 一. Though it has a much simpler shape, it certainly causes confusion here and there.

I experienced that when a Facebook friend wrote the following sentence in reply to a comment of mine:

一理はありますね。

I found the first word in the dictionary:

一理 (いちり: (a) principle; (a) reason; (a) point; some truth) 1 + line of thought

Ah, so he said that my comment had some truth to it. We were in agreement ... weren't we? Just to be sure, I asked why he had said that, and he answered this way:

Eveさんのmetaphorが上手かったので、貴方の言い分も一理があると言うことです。

Your metaphor was good, so I'm saying you have a point.

上手い (うまい: skillful; successful); 貴方 (あなた: you); 言い分 (いいぶん: one's point); 言う (いう: to say)

I was even more convinced that he had agreed with me. To my surprise, I found out from my language partner that this was not the case!

Kensuke-san told me that my Facebook friend didn't entirely share my viewpoint; he agreed with only about 70 to 80 percent of it. When I asked Kensuke-san how he knew that, he said he drew on the use of 一理. In other words, my Facebook friend had focused on the part he did agree with—the "one" (一) "line of thought" (理) that seemed acceptable to him. In the interest of preserving harmony, he had ignored the rest.

The は in 一理はありますね was another subtle indication of trouble. The Japanese usually say 一理あります (There’s something in that) without any particle. My correspondent's use of は meant “I'll give you that there’s something in what you say (but the rest is a complete load of crap).”

Okay, I might be exaggerating the last parenthesized bit! Still, what he didn't say spoke volumes—except not to me, as I suppose I had the volume turned down too far. I had been having a disagreement with someone without even realizing it.

That actually happened a second time that month, and though this next bit deviates from the topic of 一, it certainly ties in with the embarrassment of not knowing that someone has cast aspersion on your point of view.

My proofreader, Chida-san, had told me that his surname originated in Miyagi and Iwate Prefectures. After noting that a friend of a friend on Facebook had the same surname, I happily told that stranger what I had learned from my proofreader.

Here's the reply I received:

「千田=ちだ」という苗字は、宮城・岩手発祥と理解していますが。ちなみに私は青森県出身です。

My surname is Chida. I understand that it originated in Miyagi and Iwate Prefectures. By the way, I’m from Aomori Prefecture.

苗字 (みょうじ: surname); 宮城 (みやぎ: Miyagi (Prefecture)); 岩手 (いわて: Iwate (Prefecture)); 発祥 (はっしょう: origin); 理解 (りかい: understanding); 青森県 (あおもりけん: Aomori Prefecture); 出身 (しゅっしん: person's origin)

Everything seemed to be in order. His statement appeared to confirm what I'd just said and was so mild that it didn't dawn on me that there was a problem.

Just in case, I asked Kensuke-san about it. He disagreed! As he explained, Chida-san couldn’t be sure that the name originated in those prefectures. There must be various theories about the origin, Kensuke mused, and because Chida-san is from Aomori, the idea doesn’t fit for him.

And what was the sign of this disharmony? Merely the が at the end.

In other words, you could listen to the whole sentence, thinking that all was well, only to find out at the last moment that perhaps this was not so. Note that I said "perhaps." To complicate matters further, a が in that position doesn’t necessarily indicate a disagreement at all. People often use it quite casually without meaning anything concrete. UGH!

Let's move on to matters that are generally much easier to handle! Here's a preview of the new essay on 概 (approximation; outline; general):

Have a great weekend! And try not to have any disagreements that you don't realize you're having!

Comments