The Order of Things

Traveling through Norway in 2008, I absorbed just a few Norwegian terms from menus. When I encountered this ad on the side of a building in Oslo, I felt excited to be able to recognize the words for "milk" and "chocolate."

Photo Credit: Eve Kushner

But did melkesjokolade mean "milk chocolate" or "chocolate milk"?! Looking at the ad, I couldn't tell. I guessed the former, and I was right!

Though I had never thought about it before, I realized that there's an enormous difference between milk chocolate and chocolate milk!

Distinguishing between the following terms is similarly important:

乳牛 (にゅうぎゅう or ちちうし: milk cow; dairy cattle) milk + cow

牛乳 (ぎゅうにゅう: cow milk) cow + milk

Here's another example, one that I've just encountered in writing essay 1731 on 碑:

碑石 (ひせき: stone used in a monument) stone monument + stone

石碑 (せきひ: monument made of stone) stone + stone monument

It's easy to think that when you see two kanji in a compound, all you need to do is consider the individual meanings, and then you'll easily grasp the definition of the whole. But characters aren't as autonomous as pearls strung together in a necklace. Rather, they form syntactic relationships. That is, sometimes one leans on the other—but in which direction? The order can matter a great deal.

I ran across this issue in essay 1987 on 臼 (mortar; millstone; hand mill), which posted last week. There I presented this word:

石臼 (いしうす: stone mortar; millstone; stone mill) stone + mortar

And I noted that Nelson’s dictionary contains the inverse, an obscure term that he defined as "stone mortar; millstone; stone mill":

臼石 (うすいし: stone mortar; millstone; stone mill) mortar + stone

However, as I said in the essay, my proofreader doesn’t see how 臼石 could mean “mortar.” Here's his view of the situation:

• 石臼 sounds like a mortar made of stone. In this word, he says, the 臼 matters.

• 臼石 sounds like a stone with a depression that makes it resemble a mortar. In this word, he says, 石 would be the important part.

As it turns out, Nagano Prefecture has a tourist attraction called 臼石 (うすいし). Exactly as my proofreader reasoned, it’s a stone with a depression that makes it resemble a mortar! Not much of a tourist attraction, I fear, but kudos to my proofreader for his logic!

Although he was right, I felt puzzled. I’ve encountered scads of compounds that are synonymous when inverted. Take, for example, these pairs:

習練 (しゅうれん: training, discipline, drill) to learn, train + to refine, train

練習 (れんしゅう: practice, exercise) to refine, train + to learn, train

腹切り(はらきり: ritual suicide by disembowelment) belly, guts + cutting

切腹 (せっぷく: ritual suicide by disembowelment) cutting + belly, guts

平和 (へいわ: peace) flat, even, calm + Japan, peace

和平 (わへい: peace) Japan, peace + flat, even, calm

In the last example, the two words have slightly different meanings, in that 平和 is more abstract, whereas 和平 means something akin to "ceasefire." Still, peace prevails.

Despite this selection of synonymous pairs, that proofreader and another one have convinced me that the second kanji in a compound tends to be the more important one. That is, the first often leans heavily on the second.

That's no small thing in this world of primogeniture, where the eldest sibling seems to have all the power. Once again, things are topsy-turvy in kanji-land! Being number one doesn't always mean being 一番 (いちばん: best)!

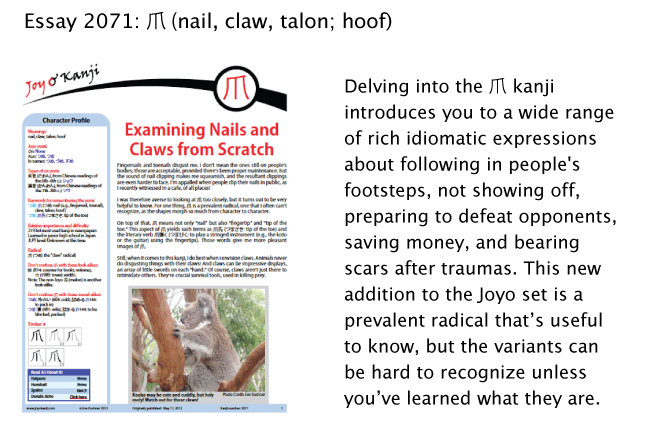

In other news, essay 2071 on 爪 (nail, claw, talon; hoof) has posted, featuring pictures of cuddly animals with fearsome nails, talons, and claws:

I'm talking not only about the koala on the cover but also about my dog Kanji, who has strikingly black nails:

Photo Credit: Eve Kushner

Have a great weekend!

Comments