At Play in the Fields of Kanji

You know how some weeks have certain themes, where a particular type of thing keeps happening for no apparent reason? You sometimes hear, "Oh, Mercury is in retrograde," and although that might sound like an explanation of sorts, it doesn't really cut to the heart of the bewilderment.

In my life the recent theme has been a flood of feedback about Joy o' Kanji. Well, "feedback" is euphemistic. People keep writing to tell me about mistakes.

Sometimes the criticisms have been accurate. One sharp reader noticed inconsistencies in "Sticky Stroke Counts," prompting my amazing proofreader Lutlam to dive into a sea of arcane rules about the number of strokes in a few odd radicals, determining how these change under a multitude of conditions. Actually, he had already done tons of research on this issue, enough to help me write the first 10 drafts of the piece, but the discovery of two errors sent him back down that road, and so much farther! He even ended up calling a dictionary publisher to sort out one muddled part of their book. This was all for the good; the piece is much improved as a result.

Other criticism has had no validity at all, bringing to mind this term from essay 1188 on 屈 (to bend):

屁理屈 (へりくつ: quibble; hair-splitting; argument for argument’s sake; frivolous objections) passing gas + reasoning (last 2 kanji)

Funny breakdown, huh?! If I say that someone is producing nothing but 屁理屈, I view his reasoning (理屈, りくつ) with contempt, as if all his quibbles are worth less than a fart!

For awhile, the pieces of criticism collected in my mind and formed a frenzied energy, the repetitive and agitated thoughts swirling around a big center. And what was at the center? A sense of vulnerability, as well as loneliness, despite all the contact with people. Whether or not the comments had merit, they threatened to pull me back into a dangerous place, one that I inhabited for years and years.

Back when I attended a rigorous boarding school in my teens, I lived on edge all the time. There was no break; the trimesters were intense and fast-paced, and we had Saturday classes every other week. Pop quizzes cropped up far too often for my liking. It seemed that many teachers were out to catch us unprepared. Living at the school, I found no ways to escape the pressure, or not any healthy ways! Well, in my first year there, I had wanted to live a balanced life, so I had gone on lots of relaxing bike rides. These seemed to keep me sane, but they certainly didn't help me finish my homework on time. By the end of that year, traumatized by the shame of winning no prizes on Prize Day (and further wounded by an authority figure's cutting comments), I embraced a perfectionism that purported to protect me against any future criticism. I made mountains of index cards. I stopped believing that I was allowed any free time at all; every spare moment needed to go toward studying. I forced myself to forgo sleep and food at critical times—for days on end sometimes. I needed to whip my inner slob into shape. At some level, I think I went insane.

Years have passed, and I eventually found more balance and peacefulness, but I still feel that I'm penalized whenever I relax. A few years ago, I gave the first speech of my life, a 30-minute talk that kicked off an architecture conference! For months beforehand, I worked myself into a tizzy about what I would say and how it would go. Finally, with all preparations in place, I decided that being tense would only hamper my presentation, so I treated myself to a massage the day before the event. The session was fabulous! All tension drained from my body and mind. Afterward, I drove home, just two miles away, and in my dream state I coasted through a stop sign. Of course, a police officer was sitting there, waiting just for me! Oh, how unfair it seemed for him to stop me, unaware of how miraculous it was that I had actually relaxed. But in a way, he confirmed what I came to believe many years ago about whether this is even permissible.

The following term comes to mind:

油断 (ゆだん: to drop one’s guard, to be careless, negligence; unpreparedness)

This word, which breaks down as oil + to terminate (one's life), dates back to a time well before cars, so the oil isn't the sort found at the gas station. Instead, it's the kind that used to light lamps and such. There are multiple theories about the etymology of this term, but four major Japanese dictionaries mention this one: In ancient times, a king commanded his servant to walk across the court holding a jar of oil. If he spilled so much as a drop, the king would have him killed.

Okay, that story leaves me furious with the king and his rigidity. But on a day-to-day basis, I think I'm not unlike that ruler when I respond to my own goofs!

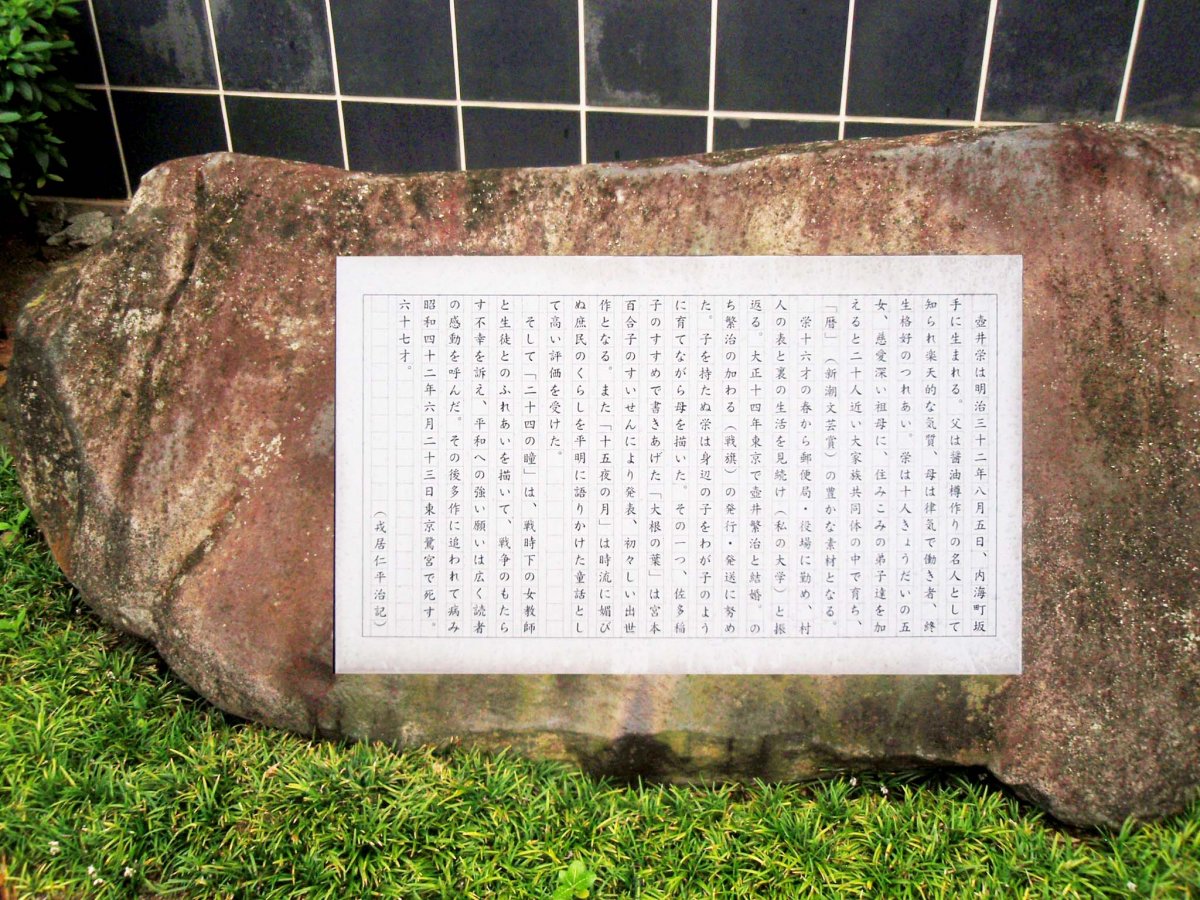

Speaking of ridigity, when I went to Shodoshima last month and visited the set of Twenty-Four Eyes, I came upon this plaque:

Photo Credit: Eve Kushner

The movie was about a school, so what we're seeing here is a metal version of genkoyoshi (原稿用紙, げんこうようし), the grid paper on which Japanese schoolchildren write essays vertically. I discussed such templates in Crazy for Kanji, listing the strict rules that kids must follow, putting one kana or kanji to a square. The same goes for punctuation marks, which also can't go at the top of a column. There is absolutely no margin for error, so to speak. If you miss anything at all, you can't just "caret" it in; you have no choice but to erase and start over at the point of error.

Who can learn when there's no room to breathe? The playful mind absorbs so much more than the mind in a locked-down state, a mind that senses that someone is about to pounce.

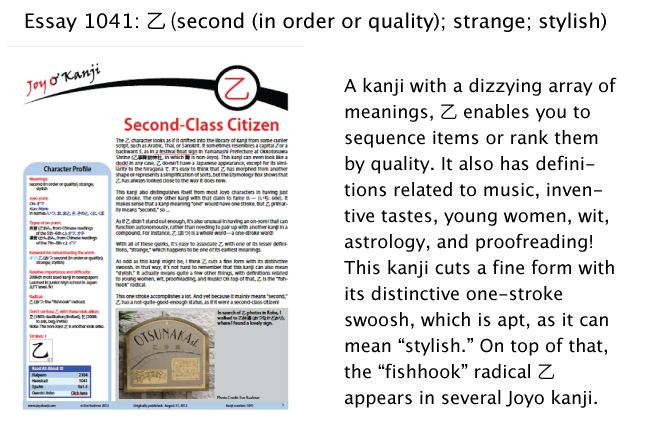

A section of essay 1041 on 乙 (out today!) reminded me of the tension that I associate with educational environments. As I wrote, the Japanese sometimes use 乙 for ranking items, so teachers would use this symbol in grading papers and tests. Then, with a massive educational overhaul in 1941, the Japanese began using the following grading system:

秀 (しゅう: excellent)

優 (ゆう: very good)

良 (りょう: good)

可 (か: acceptable)

不可 (ふか: unacceptable)

University professors sometimes use these rankings today, often omitting the first gradation. Nowadays, teachers in primary and secondary schools mainly use 5-4-3-2-1 for grading, where 5 is the best score. Another possibility for elementary school is a three-level set of comments:

たいへんよくできました (very well done)

よくできました (well done)

もうすこしがんばりましょう (Let’s try a little harder, shall we?)

I've never experienced any of these grading systems, but they nevertheless fill me with a profound sense of unease—the discomfort of having another person evaluate you.

In Tokyo last month, I spent a bit of time with Jack Halpern, who is famous for his kanji dictionaries. He has been a hero of mine for speaking 10 languages and knowing a bit about at least seven more. When I asked his secret, he said he loves corrections and never finds them embarrassing.

Can a human truly achieve that state? I will never, never know that feeling.

What can one take from this in terms of kanji study? Japanese in general (and kanji study in particular) is all about rules. We see this all too clearly with genkoyoshi and stroke count issues, for starters, not to mention nitpicky rules about which strokes cross others and which ones don't. Oh, how this made me crazed when I took kanji classes and faced final exams that lasted two to three hours. We needed to draw hundreds of kanji from memory. Before every final, I would put aside all work for three days and do nothing but study, which meant that I became possessed. The insanity didn't end with the test. After one exam, I went out with my closest friends to blow off steam, and when someone made a driving decision with which I disagreed, I lost it in a way that was foreign to everyone unlucky enough to be in the car with me. I had no idea I could be so loud!

The good news is that if these characters can drive one insane, they can also lead the way out of this twisted-up place in the brain and soul. That is, they contain the seeds of both a disease and its medicine! This sentence from essay 1041 comes to mind:

甲の薬は乙の毒。

One man’s meat is another man’s poison.

甲 (こう: the 1st party); 薬 (くすり: medicine);

乙 (おつ: the 2nd party); 毒 (どく: poison)

Although the English translation mentions "meat," the Japanese actually refers to medicine. Literally, then, "One man’s medicine is another man’s poison."

The "medicine," in the case of kanji, is play! I'm talking about the sheer delight that I find in words such as these (to pick some at random):

積ん読 (つんどく: buying books and not reading them)

Oh, to live in a culture that gives rise to such words!

先取り(さきどり: (1) receiving in advance; taking before others; (2) anticipatory completion; finishing another person's sentence in anticipation of what is likely to be said next)

I love the last meaning!

消化 (しょうか: (1) digestion; (2) thorough understanding; (3) selling accumulated (excess) products; dealing with a large amount of work)

Although English speakers talk about "digesting" a tough bit of news, these definitions seem infinitely more charming in the Japanese context, especially when you think of 消 as "to extinguish, eliminate, obliterate."

When it's at play, the mind soars past self-imposed boundaries and enters a boundaryless state—even though the playing field has its own set of rules. Play is paradoxical in that way. I play tennis every Sunday, and while I'm on the court, nothing is more important than that yellow ball. Of course, that could be a big clue that I've blown something else out of proportion. But on the contrary, while the ball is at the center of my attention, nothing else can be, and all the agitation that built up over the week finally blows away like so much dust.

Play does the same thing for me as sleep. Both give me a total break from life and leave me ready to return and give it another go. I'm really quite lucky that returning to work means having a chance to romp in the fields of kanji all day. Yes, there's certainly hard work to be done. But doing something I love, and working with something inherently delightful, means that I break free over and over, finding a joy I could never have imagined many years ago.

Here's a preview of the new essay on 乙:

A word to the wise—if anyone emails me about so much as a missing comma in the coming week, I'm going to rip their fricking heads off!

Comments