Rabbits and Rebellions

I ended the last blog by mentioning a wonderful piece of art:

To resurrect my long-dormant French, I've been taking leisurely walks with a woman from France, so I felt extra glee when I saw the French title and realized two things about the word grenade:

• Grenadine syrup must come from pomegranate juice! (It does.)

• A pomegranate looks like the sort of grenade used in wars, and that must be the source of the word in English! (Yes, that's right! The French extracted the word from the Spanish granada, "pomegranate," which came from the Latin grānātus, "seedy.")

I didn't share these realizations with you before because they had no connection to Japanese. Now they do.

Yesterday, as I was telling my language partner Kensuke how much I love "aha moments" in language study, I used these recent discoveries as examples. To communicate all this, I needed the Japanese for "pomegranate":

ザクロ (柘榴: pomegranate, Punica granatum) wild mulberry + pomegranate

Both kanji are non-Joyo. I don't know why the first contains the 石 (stone) component, and it's intriguing to know that the Chinese use 石榴 for “pomegranate."

As I found on Breen's site, 石 combines again with 榴 in this great palindrome:

石榴石 (ざくろいし: garnet)

Ah, a garnet is the color of a pomegranate, so that must be what's going on here. Yes! Or mostly yes! A garnet can be red, yellow, or green, but one dictionary says that the Japanese term comes from the Latin grānātus because the shape and color of a red garnet resemble those of a pomegranate. (The shapes are similar?!)

Kensuke didn't know what 石榴石 represented, so I showed him a picture of a garnet, prompting him to exclaim, “Oh, is this a すいしょう?" He typed the word:

水晶 or 水精 (すいしょう: (rock) crystal; crystallized quartz)

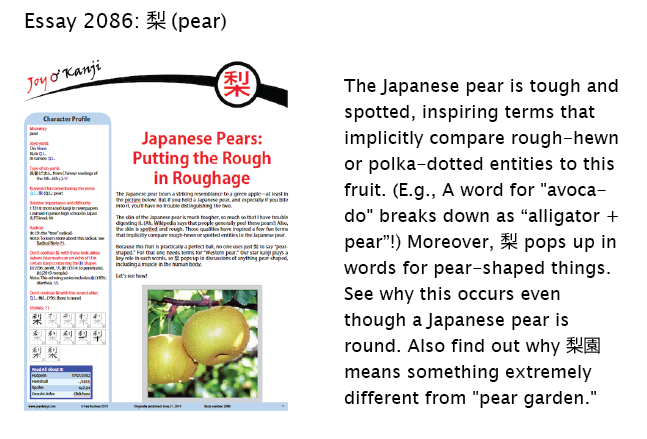

It was my turn to express excitement. I told him I had just published essay 2086 on 梨 (pear), which includes this sign from Hong Kong:

In writing about that picture (which advertises three types of juice), I learned that a 水晶梨 (すいしょうなし) is a type of pear grown in Japan! The sign likely refers to juice made from that pear.

As thrilled as I was about all this, I wanted to return to the pomegranates that inspired these findings, so I explained what a grenade was. Kensuke supplied the corresponding term:

手榴弾 or 手りゅう弾 (しゅりゅうだん or てりゅうだん: hand grenade; grenade)

Look! Our pomegranate kanji makes yet another appearance! Could it be that the Japanese or Chinese replicated the French or English word for this weapon?

Not quite. The word 榴弾 (りゅうだん) means “high-explosive projectile," and 手榴弾 is one that can be used manually (that is, thrown by hand). But that doesn't explain why 榴 lies at the heart of 手榴弾. Fortunately, Japanese Wikipedia does, saying that ripe pomegranates often burst open, much as grenades do. (That's unexpected! And I've found that pomegranates do this spontaneously when they're still on the tree, not when sliced, as I imagined.)

I had yet another reason to feel excited. The 弾 kanji figured prominently in a conversation I had last week after a yoga class. Yoga poses can be boring and hard, so I amuse myself by gazing at everyone's tattoos. (I'd say four out of five people in my yoga classes have tattoos. I keep wondering whether they're a representative sampling of the general population and whether we have no idea how tattooed most people are because they're generally more clothed than in a yoga class. Or is it that, as one self-proclaimed tattoo expert in my class told me, seekers gravitate toward both yoga and tattoos?)

Anyway, the woman next to me had a complex array of straps covering her back, so I couldn't make out the tattoo underneath, but I was sure it was kanji. After class I asked to see it, and she let me pull a strap aside for a clearer view. Ah, it wasn't kanji at all! Instead, it was the Sanskrit symbol for om, the chant yogis often do!

"The kanji you want is on my ankle," she said, pulling up her legging. I recognized the tattoo as an attempt at 弾, but the 田 part was messed up, missing an internal stroke.

"In my one act of rebellion at age 16," she said, "I went down to this shady tattoo shop and asked what kanji he had for music. The only one was 弾. I can't quite remember what it means," she said sheepishly.

"It's about playing a stringed instrument."

She blushed. "I play the flute, not any stringed instruments!"

Just to be sure, I located the definitions of 弾 on JOK: "projectile; to play (stringed instrument); bounce back." I said the first definition had to do with bullets and that sort of thing.

"A projectile! Oh, great!" she said, laughing off what she could no longer do much about.

She said that the tattoo always reminds her not to act on impulse. It's a permanent reminder of how she was thinking—or not thinking—at age 16.

I relayed all this to Kensuke, but he didn't know "rebellion," so I said that we use "rebellion" two ways. First, there's the kind where a small group doesn’t want to obey the government. I pasted in this term as a historical example that he would surely know:

藤原仲麻呂の乱 (ふじわらのなかまろのらん: Fujiwara no Nakamaro Rebellion)

He understood right away. And I said with a burst of enthusiasm that that must be the inspiration for the second type—kids who don’t want to do what their parents say. Another aha moment!

Here's a sneak preview of the latest essay:

Catch you back here next time!

❖❖❖

Did you like this post? Express your love by supporting Joy o' Kanji on Patreon:

Comments