Random Jottings

There's nary a hiragana to be found on this book cover, but I suppose that's fitting for a work covering the history of yojijukugo (四字熟語, よじじゅくご: four-character compounds):

The title ends with this term:

漫筆 (まんぴつ: random jottings) random + writing

I mention that because I included this book cover in the new essay 1838 on 漫, so I want to draw your attention to that kanji.

Here's the full title:

「四字熟語歴史漫筆」

Random Jottings on the History of Yojijukugo

歴史 (れきし: history)

The new essay has quite of bit of content on 漫画 (まんが: cartoon, comic, comic strip) but goes way beyond that. For me, several surprises emerged from that essay, including these:

• The kanji 漫 primarily means "random," even in the word 漫画.

• The word 漫画 once meant something entirely different from what it means today.

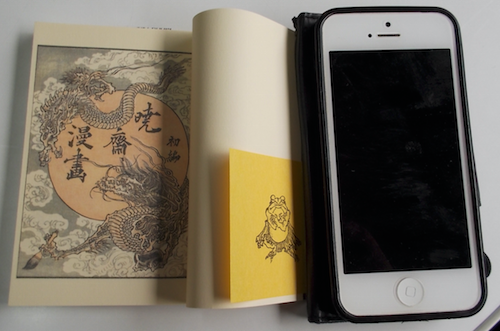

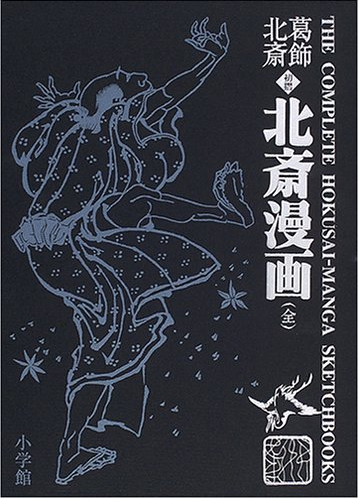

In the era of the artist Hokusai (北斎, ほくさい: 1760–1849), 漫画 represented “random drawings." So it is that a famous and voluminous collection of Hokusai's random drawings is titled 「北斎漫画」, Hokusai Manga. The book includes Hokusai’s sketches of landscapes, flora and fauna, everyday life, and the supernatural. Here's the cover of one edition:

I mention all this not just because I'm fresh from publishing essay 1838 but also because my proofreader Lutlam recently visited the Kawanabe Kyosai Memorial Museum in Saitama Prefecture. The artist Kyosai Kawanabe (1831–1889) also published a collection of random drawings:

The title syntax is like that of the previous book: 「暁齋漫画 (きょうさいまんが)」.

Lutlam bought the book, telling me that it's bound in the traditional Japanese way (known as 和綴じ (わとじ), which excited me because I've blogged about that type of binding. Furthermore, he noted that the book is as small as an iPhone:

Photo Credit: Lutlam

A miniature book is called a 豆本 (まめほん)—namely, a book (本) as small as a bean (豆). I've also written about the word 豆本—in essay 1640 on 豆 (bean; miniature; "bean" radical)—so I was thrilled to revisit the concept and see it in action.

I will say, though, that I'm stumped about one thing. Why make the book so small when it's supposed to be celebrating the man?! (Oh, Lutlam tells me that the miniaturization keeps costs down because publishing such artwork at a normal size with Japanese binding is prohibitively expensive for customers.)

I knew nothing about Kyosai, so I read about him in English on a Wikipedia page, and I was thrilled to find this passage:

During the political ferment which produced and followed the revolution of 1867, Kyōsai attained a reputation as a caricaturist. His very long painting on makimono "The battle of the farts" may be seen as a caricature of this ferment.

Oh! So many things in there!

First of all, there's "ferment" as a figurative expression. I recently wrote the forthcoming essay 1425 on 醸 (to brew, distill; cause), and as you can see from the simplest word in which it appears, literal brewing has given rise to the expression "to give rise to":

醸す (かもす: (1) to brew, distill; (2) cause, give rise to)

When trouble is mounting, discontent is slowly fermenting and taking on another form. That is, it's "brewing." For reasons I'll never understand, I find it extra-gratifying that Japanese and English are alike in having this figurative spinoff.

The Wikipedia text also calls Kyosai a caricaturist. Well, that's something else I learned about in essay 1838, where I discussed the word 戯画 (ぎが: caricature; cartoon, comic), noting that it has some meanings in common with 漫画. I then mentioned that whereas 戯画 typically delivers criticism, 漫画 is neutral.

I find the concept of caricaturing intriguing, partly because I have never considered it deeply. We hear about satire and parody, but caricatures? Not as much. I associate them mainly with American beach boardwalks, where you're almost certain to find an artist who will distort your face for a buck or two. (I have no desire to see my worst features magnified. You?)

In the current political climate, caricaturing leaders could be particularly attractive to those who feel powerless, though laughing at the rulers is also shockingly risky.

Mocking anyone seems cruel, but when you lack power and feel oppressed, sometimes it's all that you feel is left to you to do. I go back to the comment (originally from Lutlam) that 戯画 typically delivers criticism. That feels important.

So does this from Wikipedia: "Kyōsai is considered by many to be the greatest successor of Hokusai (of whom, however, he was not a pupil), as well as the first political caricaturist of Japan."

Curious about all of this, plus of course "The battle of the farts," which after all "may be seen as a caricature of this ferment," I was eager to see how that rich passage was represented in Japanese on the corresponding Wikipedia page about Kyosai.

Alas, the paragraphs on each page were total mismatches, and I couldn't locate much of what I wanted in Japanese. The best thing I found was the name of that battle-related work:

「放屁合戦絵巻」

The Battle of the Farts

放屁合戦 (ほうひがっせん: farting battle);

絵巻 (えまき: picture scroll)

And this title has enabled me to Google the artwork, and ... oh dear! It's even grosser than I imagined! But not to fear. Although such drawings have certain powers, malodorousness is not one of them!

If you want to know more about the piece, here's a good blog from Tofugu. That blog links to Naruhodo, which quotes Henshall on the matter of such competitions: "Similar drawings were used to ridicule westerners towards the end of the Edo period."

That may not actually be the case with 「放屁合戦絵巻」. My proofreader can find no evidence that it relates to either Japanese politics or to Westerners. He thinks that, as the Tofugu blogger concludes, farting is simply funny, and there's nothing deeper here than that.

So there you have it. Well, actually, I've touched on so many things that I'm not quite sure what you have. And that's the nature of random jottings!

Here's a preview of essay 1838 on 漫:

Back with you in two weeks!

*****

Did you like this post? There's an easy way to let us know!

Support Joy o' Kanji on Patreon:

Comments