Repetition Compulsion

As I wrote the new essay 1535 on 束 (bundle; bunch; to tie up; to bind), confusion arose over this phrase:

束の厚み

The entities on either side of the の meant "thickness." Wasn't that redundant? Had someone written this wrong?

I consulted the proofreader who had supplied me with the phrase, and he acknowledged that although it might seem redundant, Japanese abounds in such repetitions, as in these examples:

身長が高い (height (of body); stature)

身長 (しんちょう: height); 高い (たかい: high)

肉厚が厚い (thick; meaty; fleshy)

肉厚 (にくあつ: thickness (of meat or flesh or of certain objects)); 厚い (あつい: thick)

熱いお湯 (hot water)

熱い (あつい: hot); お湯 (おゆ: hot water)

髪の毛 (hair on the head)

髪 (かみ: hair on the head); 毛 (け: hair)

The last example made things snap into focus for me because I recently grappled with 髪の毛 in essay 1706 on 髪 and ended up writing this, more or less:

The 毛 might seem to tell us nothing extra; it doesn’t clarify the 髪. Conversely, the 髪 in this phrase does specify the type of 毛 intended. That is, if you’re mentioning any kind of hair on the body, you’ll likely use 毛, which can represent anything from eyebrows (眉毛, まゆげ) to leg hair (脛毛, すねげ, in which 脛 is non-Joyo). In such a context, if you want to speak about tresses, you need to modify 毛 with 髪の, producing 髪の毛.

With this new frame of reference, I could at last grasp 束の厚み, a specialized word that bookbinders once used. I explained it this way in the essay:

As you can see, 束 as つか was a technical term for “thickness of books.” It may look redundant to say 束の厚み if 束 means “thickness,” but that’s not the case; more specifically, 束 meant “thickness of a book without the cover.” So with 束の厚み, the 束 specified the type of thickness (厚み) at hand.

Redundancy in Japanese takes many forms. It often turns out to be perfectly acceptable.

For instance, in scads of compounds, one kanji repeats the meaning of the other and seems superfluous. These examples come to mind:

石碑 (せきひ: stone monument) stone + stone monument

森林 (しんりん: forest, woods) forest + grove

仙人 (せんにん: mythical being) mythical being + person

If you dispensed with 石, 林, and 人 respectively, the meaning would stay intact, though the remaining, shortened yomi would certainly be harder for people to understand.

This issue becomes even more salient when two halves of a word mean exactly the same thing:

婦女 (ふじょ: woman) woman + woman

束縛 (そくばく: restraint; shackles; binding) binding + binding

眼目 (がんもく: main point, gist) eyeball + eye

It's hard to believe that the last term doesn't mean "eyeball"!

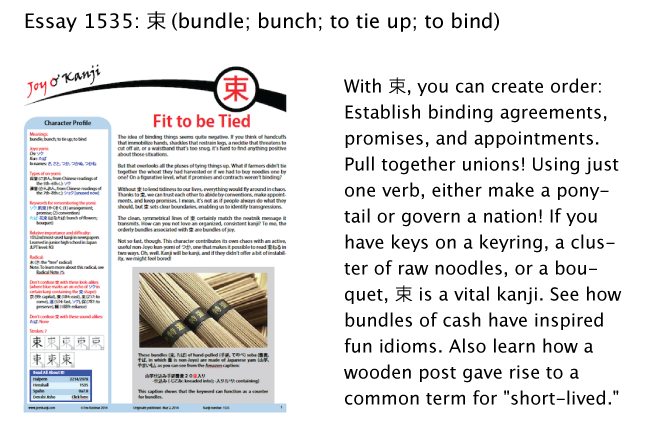

Photo Credit: David Jacobson

Every kanji here has a "tree" radical, 木! This writing may not mean anything, says my proofreader, though the store may sell objects made from various kinds of wood.

In sentences such as the next one, it's fine to have redundancy:

彼は新井兄弟の弟だ。

He is the younger of the Arai brothers.

彼 (かれ: he); 新井 (あらい: surname); 兄弟 (きょうだい: brothers); 弟 (おとうと: younger brother)

Another example comes from the forthcoming essay 1920 on 戻 (to return; re-; revert; resume; restore; go backward). This sentence features the keyword 逆戻り (ぎゃくもどり: relapse):

寒さがぶり返して先月の季節に逆戻りしました。

Last month's cold weather has returned.

寒さ (さむさ: coldness); ぶり返す (ぶりかえす: to return); 先月 (せんげつ: last month); 季節 (きせつ: season)

Using both ぶり返す and the keyword in one sentence certainly seemed redundant to me, but my proofreader disagreed: "The combination of ぶり返す and 逆戻り is not redundant at all because both are idiomatic expressions." He couldn't imagine omitting either one from this sentence.

Then there's this phrase, which used to be in essay 1535 on 束:

組合が結束する

to have the union come together

組合 (くみあい: union); 結束 (けっそく: union)

The する turns 結束 into a verb meaning "to unite," but still we have a union uniting, which sounds funny in English. Not so in Japanese.

Lest you start thinking that anything goes when it comes to repetitions, let's examine this sentence, which I found in Breen:

その双子はさやの中の2つのエンドウ豆のように似ている。

The twins are as alike as two peas in a pod.

双子* (ふたご: twin); さや (莢: pod, a non-Joyo kanji); 中 (なか: inside); エンドウ豆 (エンドウまめ: pea); 似る (にる: similar)

I learned that though this is grammatically perfect, it sounds quite redundant (and appears to be a direct translation from English, which must be where the problem arose). My proofreader rewrote it, producing a much more concise sentence:

その双子は瓜二つだ。

瓜二つ (うりふたつ: two peas in a pod, in which 瓜 is non-Joyo)

This 瓜二つ literally means "as alike as two melons" and comes from cutting a gourd in half and then finding that the two pieces look identical. (Wouldn't that be true with many types of produce?)

I bet all languages have acceptable redundancy in certain areas and not in others. It seems very hard to predict when it's going to be okay or not. Perhaps Japanese, which is after all unique in having the duplication kanji 々, accommodates more repetition overall.

Photo Credit: Eve Kushner

In essay 1432 on 辛 (spicy; bitter; dry taste; salty; severe; painful), I presented this photo of a package of kelp (昆布, こんぶ). It bears the phrase ピリッと辛く, combining the following words:

ピリッと (a mimetic word representing the way one’s tongue tingles or stings when one eats spicy food)

辛く (からく: spicily)

It’s best to take ピリッと辛く as one phrase meaning “spicy.” The syntax seems redundant, but according to my proofreader, reiterating this idea makes the language more vivid, spicing up the text!

In case you're wondering, 仕上げる (しあげる) means "to finish up." If you eat this wasabi-flavored kelp, it will sting your mouth in the spiciest of ways until it finishes you off. Oh, sorry, that’s not right! The verb is “to finish up.” That is, they finish up the seasoning process by making the kelp spicy.

My proofreader Ryo-san made a comment relevant to all this. We had the following exchange over several emails:

❖❖❖

Ryo: Things that look apparently easy for native speakers are sometimes most difficult for nonnatives. I personally call it やまと言葉, which may be literally put as "the classical language (of Japanese or of English)," but what I mean is "the language that comes from within naturally and intuitively."

Me: Your thoughts on 大和言葉 are quite interesting!

Ryo: Thanks for putting やまと言葉 all in kanji. When I wrote it yesterday, I kind of hesitated to write it all in kanji, because 英語の大和言葉 looked strange for me. So I intentionally used ひらがな for 大和. I understand that 大和 is the ancient name of Japan, just as we say 大和民族, the translation of which must be "the Japanese race." In fact, I am thinking of writing an essay on 英語の大和言葉 sometime in the future.

Me: Are you at all worried that 英語の大和言葉 will sound strange to native Japanese speakers? Or are you trying to get their attention with this unusual wording?

Ryo: Because kanji are ideographic, 大和, when we see it, has a direct message as "ancient Japan." 大和言葉 means "expressions peculiar to the Japanese language."

Therefore when writing about the 大和言葉 of the English language, I think I should use ひらがな, hoping to make it blend better in with the phrase as 英語のやまと言葉. Besides, using ひらがな helps the wording look softer. By 英語のやまと言葉, I mean "daily expressions easy for native English speakers to understand but hard for nonnative speakers to figure out."

Me: I just wonder if even hiragana won't be enough to break the association between Old Japan and what you're trying to say.

Ryo: I guess you are right. Even though it is written in hiragana, it may not be able to get off the leash of the meaning.

❖❖❖

To clarify his thoughts, he actually wrote the last comment in Japanese, as well. Here's how the second sentence appeared:

平仮名で「やまと」と書いても、言葉の束縛から自由になれないかもしれません。

Even though it is written in hiragana, it may not be able to get off the leash of the meaning.

平仮名 (ひらがな: hiragana); 書く (かく: to write); 言葉 (ことば: words); 束縛 (そくばく: restraint, shackles, confinement); 自由 (じゆう: freedom)

The "leash" of the meaning! As someone who frequently walks a naughty, stubborn beagle mix on a leash, I love it! Imagine if instead I had a definition on the other end of the leash!

I included this anecdote because 英語の大和言葉 is actually the opposite of a redundancy. If anything, it's a paradox. Also, what a coincidence that I came upon this exchange today, just when I've written about 束縛 in essay 1535 and above! As I mentioned earlier, this word breaks down as binding + binding! Sometimes repetition blows your mind!

Here's a sneak preview of essay 1535:

Have a great weekend!

Comments