Splitting Atoms

I've just finished reading the New Yorker article "Utopian for Beginners." For people like us, that piece is a must-read, as it's about invented languages and has lots of juicy tidbits, including these three:

• "Phonoaesthetics" is "that hard-to-pin-down quality which gives a language its personality and makes even the most argumentative Italian sound operatic, the most romantic German sound angry, and Yankee English sound like a honking horn."

• He "stuck out like an umlaut in English."

• A word from an invented language: "Radiidin: a non-holiday, a time allegedly a holiday but actually so much a burden because of work and preparations that it is a dreaded occasion; especially when there are too many guests and none of them help."

It says in the article that 16th-century Jesuit missionaries traveled to Asia and brought back to Europe the first substantial accounts of the Chinese language. On hearing these reports, many European philosophers were intrigued that characters "signified concepts rather than sounds, and that a single ideogram could have the same meaning to people all over East Asia, despite sounding completely different in each tongue" (p. 88).

Well, we know that the "rather than sounds" part isn't right. But what jumps out at me right now is this bit: "a single ideogram could have the same meaning" across Asia. Yes, it certainly can. However, even within one country (let's take Japan, why don't we?!), it's certainly not as simple as that!

Lately, my conversations with proofreaders have largely been devoted to what Wikipedia calls disambiguation. We've been splitting hairs about what a particular kanji means in various contexts, and it sometimes feels as hard as splitting atoms (not that I've ever tried that).

I'll give you four recent examples in the order of publication.

1. Fragrance vs. Incense vs. Perfume: 香

There's no room for confusion here; context makes it quite clear whether 香 means "fragrance," "incense," or "perfume." Of course, there's ambiguity in the English I just used; you may not know whether "fragrance" there means "pleasant aroma" or "perfume." I mean the former.

Anyway, I noticed the split between the meanings of 香 acutely during my recent travels through Hong Kong and Singapore. For example, I saw this sign:

And I said to my husband, "There's the fragrance character I just wrote about!" Shortly afterward we came upon this:

Pointing to the upper left, above the sign that forbids photography (!), I told him, "There's that incense character I keep seeing. Well, I mean, it's the same as the fragrance character." Then we ran into this sign:

Another instance of 香?! Actually, two instances! Exuberant, I started to tell him that we were again seeing 香, which can actually mean three things: "perfume," "incense," and "fragrance." But by then I felt as if I sounded crazy (and probably quite boring!), so I stopped myself and just took the picture.

2. Male Rainbows vs. Female Rainbows

Oh, I had such fun with essay 2090 on 虹 (rainbow)! As I learned, people use the following terms to discuss double rainbows in technical language:

主虹 (しゅにじ: primary rainbow) main + rainbow

副虹 (ふくにじ: secondary rainbow) duplicate + rainbow

In a double rainbow, the 主虹 is the bright lower arc, whereas the upper, faint one is the 副虹. This example deviates a bit from the pattern I've laid out; we're not distinguishing between two meanings of 虹 but rather between two types of 虹.

Photo Credit: Mariusz Szmerdt

The following sentence features both 主虹 and 副虹, as well as 虹!

「虹」は、はっきりと見える主虹、「霓」はその外側に薄く見える副虹。

A primary rainbow known as 虹 is clearly visible. A secondary rainbow called 霓 is the faint rainbow outside it.

はっきり (clearly); 見える* (to be visible); 霓 (にじ: rainbow); 外側 (そとがわ: outside); 薄い (うすい: faint)

Aside from the double rainbow primer here, we find something else of great interest—a non-Joyo kanji (霓) that means "rainbow" and that has the kun-yomi of にじ, just as 虹 does!

According to Daijisen, there's an important difference between 虹 and 霓. In a sense, they're considered to be a pair of dragons! The male dragon is 虹, and the female is 霓. The "female" is faint (that is, weak). Hmph.

3. Wizard vs. Fairy vs. Hermit: 仙

This kanji has been a doozy to define. "Wizard" and "fairy" are two possibilities, but I don't wan't to choose a gendered word as the primary definition; if I select the male "wizard," all the female fairies might be offended. Then there's "hermit," but it doesn't seem to be used as often. And anyway, once we enter the realm of hermits, we've ceased to talk about supernatural beings. That's the real problem with translating this kanji. In bridging the mortal and immortal worlds, it represents a concept that simply doesn't exist in English.

To get a handle on it, I spent an entire day examining Taoism, because that religious context gave birth to the ideas now associated with 仙. I kept The Tao of Pooh and The Te of Piglet close at hand for comfort. Just seeing Pooh's and Piglet's images on the covers of those books made me feel better!

I finally found the source of the problem. Over the millennia, the contexts in which people endowed 仙 with meaning have changed enormously. Great chasms lie between the eras and places in which the meanings shifted, and 仙 has not made it across the chasms entirely intact. The original notions of 仙 emerged with Chinese folk religions in 400–300 BCE. Then Taoism developed, absorbing and changing these ideas. Later, Japan imported ancient Chinese characters and pronunciations but not necessarily the religion that gave rise to these characters. Both Japan and China eventually modernized, of course, and concepts of wizards and fairies have become a little less than relevant to day-to-day life.

How strange it felt to lose myself in this material about ancient China, trying to make sense of old puns, as well as utterly unfamiliar ideas about health and even immortality! As I learned, these concepts have informed some of today's martial arts. Nevertheless, that's not my world. What a jolt it was to return to my 21st-century North American context at the end of the workday, wondering where I'd been!

4. Wall vs. Fence: 塀

This kanji, too, has caused a fair bit of trouble. The Japanese differentiate between 塀 and 壁. In turn, English speakers differentiate between fences and walls. Although it seems safe to translate 壁 as "wall," it certainly isn't true that 塀 always means "fence." In our discussions, I had to think very carefully about what a fence is. I realized that it's made of lightweight material (usually wood, but also metal, as in a barbed-wire fence), and it's often pointy on top. I mention the last part because I needed to tell my proofreader why it sounds strange to suggest that a cat is lying on a fence.

Our discussion kept reminding me of the 2004 Jon Stewart bit "Fence or Wall?" in which moderator Dan Rather poses this ultra-important question to a panel of presidential contenders: "In the Middle East, the Israelis say it's a fence. The Palestinians call it a wall. What do you call it?" The whole video is great, but the fence versus wall part has stayed with me for nine years. It starts at 2:53.

Is Disambiguation the Goal?

So would we want a language with no ambiguity? No, certainly not. And yet some people have worked to achieve just that. The New Yorker article that I've mentioned is a profile of John Quijada, a Californian who created the language Ithkuil, aiming to make speakers identify exactly what they want to say without hiding behind metaphors.

No metaphors?! How dull would that be?! While mentioning this goal, the article author couldn't finish the paragraph without referring to "the subterranean quirks of human cognition" and "the bugs that infect ... thinking." (I'm not sure if he was trying to avoid figurative language in that moment, but given the context, those metaphors jumped out at me as greatly ironic. In Ithkuil, by the way, one is supposed to add 'kçç to verbs when speaking ironically!)

Ithkuil uses "a mere flick of a vowel" (another metaphor!) to distinguish between "glimpsing," "glancing," and "gawking." It took Quijada 15 minutes to figure out how to express "gawking" in Ithkuil; he needed to add components to a core word in order to capture the impropriety, shock, and surprise that go into gawking. I appreciated the exercise, as it reminded me of what I love about writing emails in Japanese. When I don't know how to say something and type a word into Breen's dictionary, I see a long list of possibilities, and it forces me to clarify my thinking. Listening to the Modern English song "I Melt with You" on the radio last night drove the point home; one lyric puns on "race" in this way: "I made a pilgrimage to save this human race / Never comprehending the race had long gone by." Why do we even say "human race," and how would you explain that phrase to a foreigner?!

The New Yorker article mentions Solresol, a language that someone invented in the 19th century: "It had only seven syllables: Do, Re, Mi, Fa, So, La, and Si." (I wonder if that should have been "Ti" at the end.) Anyway, "Words could be sung, or performed on a violin. Or, since the language could also be translated into the seven colors of the rainbow, sentences could be woven into a textile as a stream of colors."

Now that I'd like to see. The question is, which kind of rainbow—male or female?!

Essay 1255 Is Out—All 27 Pages of It!

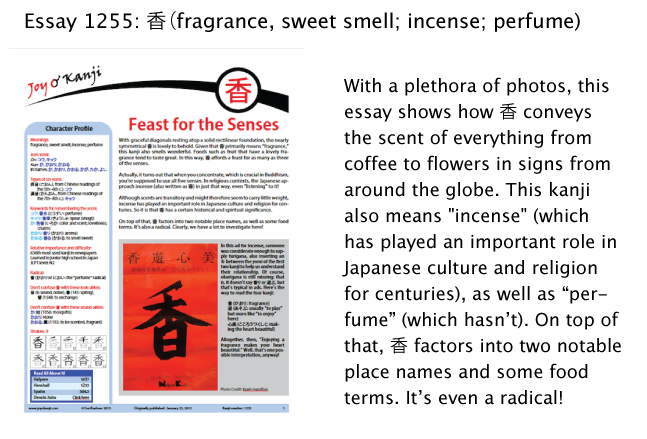

Here's a preview of essay 1255 on 香, which as you know means "fragrance" and "incense" and "perfume":

As the preview indicates, 香 doubles as a radical. I've now published essays about all 22 kanji in the junior high school set that can serve as radicals. That's been a goal for three years, and it feels big to have reached this milestone.

Here's something else that's big: essay 1255! It's a whopping 27 pages long (thanks in part to its 34 photos!), the longest ever in the history of JOK! I feel as if I've given birth to a 27-pound baby!

Have a great weekend.

Comments