Sugarcoating Reality

I hear so much about sugar intake as the culprit behind various problems that I often forget that sugar can serve a healthy purpose. That is, sugarcoating makes bitter pills easier to swallow. That can be true both literally and figuratively, not just in English but also in Japanese.

English speakers use “sugarcoat” metaphorically when a bitter reality has been made to seem more palatable.

In the figurative realm, the Japanese have this phrase:

オブラートに包む (to use a euphemism; say indirectly)

The 包む (つつむ) means “to wrap up,” and オブラート comes from the Dutch oblaat (a clear sheet made of starch). Thus, オブラートに包む literally refers to a sheet used to wrap up a dose of medicine. In the old days, that’s how the Japanese swallowed bitter medicinal powders. The sheet has no taste or odor, so it's not as if someone has sweetened away the pain!

Actual sugarcoating still plays a pharmaceutical role. Check out the following packaging:

"Sugar coated" appears in English, as does this term:

糖衣錠 (とういじょう: sugarcoated pill) sugar + clothing + pill

Thanks to 衣, the pill is “clothed” in sugar! Come to think of it, English speakers similarly say that a pill is “coated” in sugar. This wording has never once made me envision a pill in a winter coat, but 衣 has made that possible!

These pills are intended to stop 下痢 (げり: diarrhea). The large white words under 下痢 are 食あたり (しょくあたり: food poisoning) and 水あたり (みずあたり: water poisoning). The あたり corresponds to either 中り or 当り.

The active ingredient is 正露丸 (せいろがん), a beechwood extract popular as an herbal treatment for diarrhea and stomachaches. This remedy is not without its problems. If you keep it in your mouth without swallowing, your mouth will go numb! Moreover, 正露丸 smells and tastes awful—hence the need for sugarcoating.

This pill serves up even more surprises; the 露 means "Russia," and not because the remedy came from there or anything. Originally, back in 1902, the Japanese referred to it this way:

征露丸 (せいろがん: “Russia-conquering pill”) conquering + Russia + pill

That was two years before the start of the Russo-Japanese War (1904–1905), and Japanese patriotism was running high, as was anti-Russian fervor.

When the war began, the military manufactured the medicine and distributed it to soldiers to prevent the disease beriberi. It didn't actually work for that, but returning veterans sang the praises of this drug, and it became popular, says Wikipedia: "Amid the mood of victory in war, Seirogan's name became 'the cure-all that defeated Russia' and many drug-makers rushed to manufacture the pill, which became a national medicine unique to Japan."

The name せいろがん was still rendered as 征露丸 in the 1930s, as we can see in an ad from that decade:

Obviously, the patriotic theme continued.

By the way, せいろがん was not a brand name. Many pharmaceutical enterprises sold this medicine and called it 征露丸.

After World War II, the 征 (conquering) kanji was deemed politically incorrect in this context and was replaced with 正 (correct), producing the current name 正露丸.

Nevertheless, one manufacturer in Nara Prefecture on Honshu still sells the “conquering” 征露丸:

That's some medicine—it conquers not only diarrhea but whole countries, and an enormous one at that!

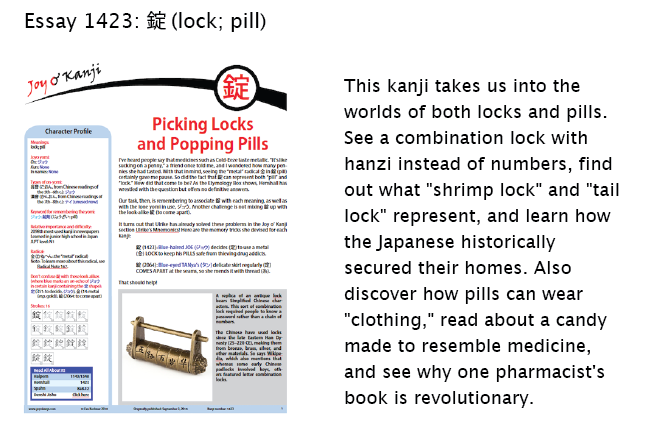

Find out much more about medicines and locks (of all the incongruous things!) in the new essay 1423 on 錠 (lock; pill). Here's a sneak preview:

Have a great weekend!

Comments