A Taste of Infinity

Let's start with a game. In the list below, match all the words that should go together, forming three groups:

| IMA | OHEYA | OKUZASHIKI |

| 正式な客間 | 寝室 | 居室 |

| チャノマ |

I'll block the answers with a preview of the newest essay:

I'll present answers with the aid of pictures because that's where this puzzle originated.

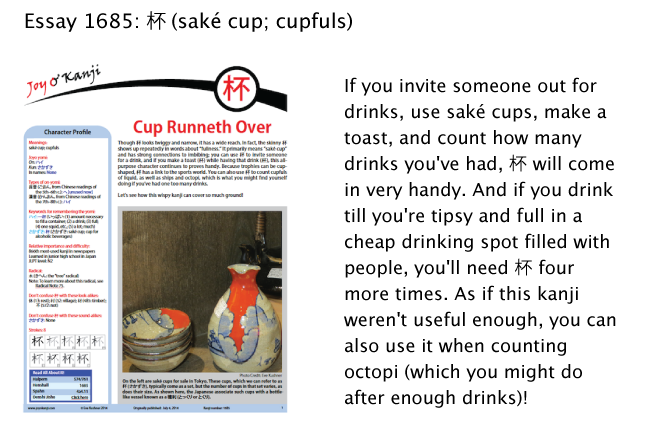

This image includes three of the words from the list: チャノマ, 居室, and IMA. The first katakana word on the sign, イマ, matches the romaji, but aside from that, why are we seeing so many mismatched words?

When I toured the Nihon Minkaen open-air folk museum in Kawasaki with my proofreader Ryo-san and his friend Hiro-san, seeing incredible examples of traditional Japanese architecture, we wondered the same thing about this sign and several others. Clearly the English is there for foreigners, and I suppose the romaji is, too, though it's of limited utility both to those who know no Japanese and to those who already do. The katakana must be for Japanese children, and the kanji is mainly for Japanese adults. But why couldn't the sign have said イマ, 居間, IMA, which would have been more consistent?

There's no way of knowing the thought process, and it doesn't matter to me at all. But I found that contemplating the mismatch was quite a puzzle in both senses of the word (that is, a game and something confounding).

According to Ryo-san, the sign says the same thing in multiple ways:

居間 (いま) = 家族の居室 (かぞくのきょしつ) = 茶の間 (ちゃのま) = living room

He observes that today, the Japanese use the word 居間 (or リビング) for "living room." By contrast, 居室 sounds too sophisticated (particularly for daily conversation), and 茶の間 sounds obsolete.

Note that 家族の居室 literally means "family living room" and that 茶の間 translates directly as "tea room." Notice, too, that the yomi of 居 changes from い in the first word to キョ in the next, whereas 間 holds steady as ま.

The next sign contains just two items from the choices I offered: 寝室 (しんしつ) and OHEYA. Those two words certainly don't match, though the romaji and katakana do. Also, whereas I associate 部屋 (へや) with any room, 寝室 suggests a sleeping (寝) function.

Ryo-san weighs in again, this time providing contextual information: "I think お部屋 means a room other than the living room, bathroom, or kitchen. The room was used in one way during the daytime and then as a bedroom at night with a futon from the closet spread out on the tatami mat."

We find OKUZASHIKI and 正式な客間 in this sign, signifying another mismatch. Although the katakana オクザシキ at the top corresponds to the romaji, there's no trace of what this word would be in kanji—namely, 奥座敷. Ryo-san defines this as "an elegant sitting room where guests are received." The 奥 (interior) suggests that this room was far back in the house. Otherwise, 奥座敷 is fairly close to the meaning of 正式な客間 (せいしきなきゃくま), which is literally a formal (正式な) room (間) for entertaining guests (客).

While we're at it, I'll share two more signs that gave us pause.

The yomi of 土間 (earthen floor) is どま, and none of the Japanese people with me had any idea what トオリ could be. The best guess was that the particular house we were seeing came from a region in which people referred to earthen floors as トオリ.

Finally, in the commercial parts of people's houses (because some of the traditional houses served both as storefronts and living spaces), we were quite surprised to see みせ in hiragana, assuming without a doubt that it stood for 店 (store). After all, it said this right below みせ:

商売をする所

商売 (しょうばい: business, transaction); 所 (ところ: place)

But we were wrong! As our guide explained, this みせ corresponded to 見せ, which came from 見せる (みせる: to show). The store owners would show customers samples of their product before selling it.

Ryo-san then joked that it was a 見せる店, a store where they showed things.

Incidentally, the product sold at this particular store was rapeseed oil (菜種油, なたねあぶら). I loved the sign hanging outside that building:

The smaller kanji on the left are 与兵衛 (よへえ: a man's given name).

Although the poor signage at an otherwise incredible museum appalled my companions, I have to say that I enjoyed our joint confusion. It might sound strange, but I often find it fun and energizing to be in a situation where things make no sense. I like seeing others reason things out because I love knowing how people's minds work. That's especially true when it comes to native speakers and kanji; I learn a great deal from seeing how they approach kanji puzzles.

Also, I have to admit that I get a kick out of seeing Japanese people stumped about kanji matters. (That wasn't the case with these particular signs, but uncertainty arose for my companions in other parts of the museum.) It's not that I'm sadistic (am I?!). Rather, their confusion shows me what we learners are really dealing with here. It confirms, as if I didn't already know it, that the Japanese writing system is infinitely complex. I like a taste of infinity. It's good that I feel that way or else kanji would have scared the pants off me a long time ago!

Have a wonderful weekend. And be sure to check out essay 1685 on 杯. That kanji seems to have infinite meanings!

Comments