A Trip Around the World

Welcome to the 300th blog post! I love round numbers like that!

Back in essay 1414 on 鐘 (bell), I wrote about a sweet known as 梵鐘 (ぼんしょう: temple bell, in which 梵 is non-Joyo), as it's shaped like a temple bell:

As you can see, it's filled with red bean paste. Now I've come across another snack with more of that paste and more metal in its name—twice as much, in fact:

銅鑼焼き copper + gong + cooking over fire

The middle kanji is non-Joyo.

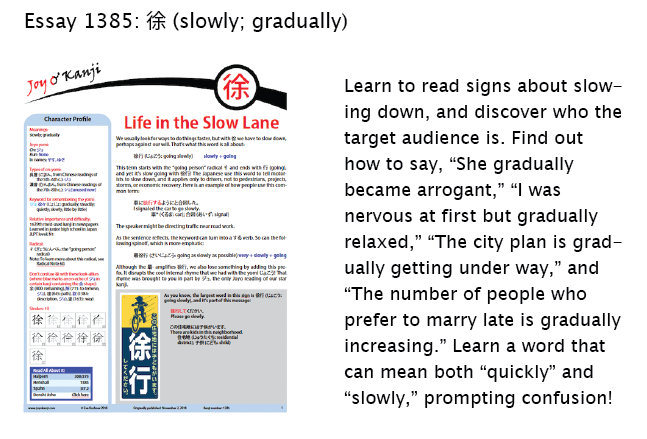

Any idea what this word could represent? I'll block the answer with a preview of last week's essay:

Here's the answer:

銅鑼焼き (どらやき: dorayaki, a dessert consisting of two small sweet pancakes sandwiched around red bean paste) copper + gong + cooking over fire

The 銅鑼 part means "gong," and people usually write that word as どら or ドラ when it's part of the name of this treat. As for the gong connection, the pancake shape resembles that of a gong.

I was unfamiliar with this dessert until recently, when I watched the movie Sweet Bean, which depicts the struggles of a dorayaki maker. Actually, that's the first half of the story, and then the film does an about-face and becomes something else entirely.

Sorry, this is a spoiler, but I read the same information online, so I'm not the first to ruin the secret. The movie then focuses on people with Hansen's disease, the up-to-date term for "leprosy."

One of the characters has suffered from this disease for most of her many decades, and physical suffering is only part of the picture. She, like many others with this disease, has been confined to a sanitarium, stigmatized and set apart from the rest of the world, ripped away from family and even deprived of clothing that her mother went to an enormous effort to make her.

I was mesmerized by the portrayal of the character's life because for some bizarre reason, I have long had a fascination with this disease. After surmounting some difficult logistics, I took a small plane to Kalaupapa, the place where Hansen's patients were confined on Hawaii and where some still live today. I also toured a hospital for Hansen's patients in Bergen, Norway. And I've read the touching novel The Pearl Diver, so I knew how such cases were handled in Japan, with many of the patients quarantined on remote islands.

But until now, I have never seen this disease as the focus of a movie. It must truly be a cinematic first. And the filmmakers took an extra pioneering step—a huge one—by including extras who actually have the disease and who are missing noses and fingers. Imagine—they've lived their whole lives in the shadows, and now they're in the limelight. To their credit, the filmmakers show these men talking and laughing with each other, as if they were regular people, which in fact they are.

I conveyed all this to my Japanese-language partner Kensuke, and he responded with the following sentence:

そういう内容の映画だと初めて知りました。

It’s my first time finding out that the movie is about that topic.

内容 (ないよう: content); 映画 (えいが: movie); 初めて (はじめて: first time); 知る (しる: to know)

There's nothing remarkable about his response. I just wanted to bring the focus back to the Japanese language, so I shared his comment!

Shibui

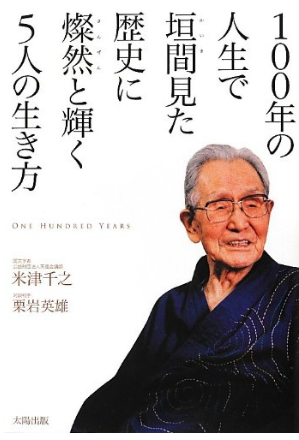

In a recent blog post I mentioned my chat with Kensuke about the word 垣間見る (かいまみる: to catch a glimpse of). In the same conversation, I showed him a book that features the word on the cover:

When Kensuke saw this image, he said 渋い (しぶい)! I then grilled the poor guy about why he had used that word and what he had meant. The term always confuses me, as it has so many meanings:

渋い (しぶい: (1) astringent; bitter; puckery; rough; harsh; tart; (2) austere; elegant (and unobtrusive); refined; quiet (and simple); sober; somber; subdued; tasteful (in a quiet way); understated; (3) sour (look); glum; grim; sullen; sulky; (4) stingy; tight-fisted)

Any explanation he offered confused me further, so I ended up asking yes-or-no questions:

Was he saying that the cover looked grim?

No.

Was he saying that the design was austere in a bad way?

No.

Did he like how it looked?

Yes.

Did he find the old man attractive?

No.

I finally ascertained that Kensuke said what he did because the cover struck him as tastefully spare. He responded favorably to the design with its abundant white space and with the old man’s picture as the only decoration.

Swirly Etymology

I then noticed the swirls on the man’s kimono and asked Kensuke if he’d ever seen such a pattern. He hadn't and didn't know what to call it, then Googled it somehow and shared this word:

唐草模様 (からくさもよう: arabesque; scrollwork)

Chinese + grass + pattern (last 2 kanji)

Whereas the kanji indicate that the item is from ancient China (唐), the “arab” in the English indicates a very different origin, so I was filled with new questions. We delved into the matter and found that, according to Japanese Wikipedia and Daijisen, no single plant is called a 唐草. Instead, several types of vines have inspired the motif.

Nihon Kokugo Dai-Jiten indicates that the pattern originated in Egypt or Mesopotamia (home to part of the Islamic world) and came to Japan via China. Thus, there's nothing inherently Chinese about the 唐草模様.

The English word "arabesque" has a more straightforward etymology. It comes from the Italian arabesco, meaning "ornament in Islamic style" and literally "Arabian."

The Newest Essay

Now that we've completed our round-the-world trip, I'll leave you with a preview of the new essay 2085 on 奈 (ナ sound), which explores several destinations within Japan:

Catch you back here next time!

❖❖❖

Did you like this post? Express your love by supporting Joy o' Kanji on Patreon:

Comments