Unfurling a Glyph

While writing the hot-off-the-presses essay 1938 on е»Ҡ (corridor; gallery), I came upon something that stumped me in a passage from Amazon Japan. How would you read the red bit:

гҖҢдёӯе»ҠдёӢгҖҚгҒЁгҒ„гҒҶгҖҒгҒ“гӮҢгҒҫгҒ§гӮҖгҒ—гӮҚйҡ гҒ•гӮҢгҒҰгҒҚгҒҹиҰҒзҙ гӮ’гғҶгғјгғһгҒ«гҖҒжҳҺжІ»еӨ§жӯЈжҳӯе’ҢгҒ«гӮҸгҒҹгӮӢж—Ҙжң¬дәәгҒ®дҪҸе®…гҒ®й–“еҸ–гӮҠгӮ’иӘҝжҹ»гҒ—гҖҒжҷӮд»ЈгҖ…гҖ…гҒ®з”ҹжҙ»гҒ®зҹҘжҒөгҒЁе·ҘеӨ«гӮ’жҺўгӮҠгҖҒжҠҪеҮәгҒҷгӮӢгҖӮ

In case you're curious about this sentence, it says that the author explores how Japanese people have lived, examining the room arrangements of their houses from different eras (Meiji, Taisho, and Showa), positing that the central corridor has been a heretofore unexplored theme, and studying the wisdom of each period.

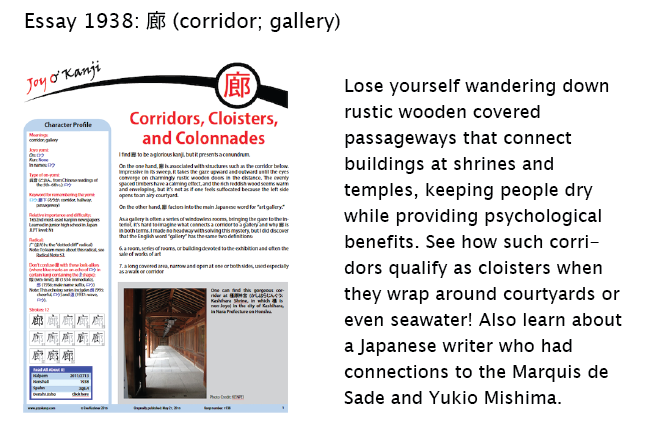

I'll let you think about the red part while I offer a sneak preview of the new essay:

It turns out that жҷӮд»ЈгҖ…гҖ… corresponds to жҷӮд»ЈжҷӮд»Ј. The word жҷӮд»Ј (гҒҳгҒ гҒ„: era) has been duplicated, creating the nuance of "each era." I don't remember ever having seen a repetition of the repetition kanji!

I always get a kick out of this little symbol. I find it as cute as an upturned nose, which it actually resembles! And I'm all the more charmed when I spot it in unexpected places.

Take, for example, this surname:

дҪҗгҖ…жңЁ (гҒ•гҒ•гҒҚ)

The symbol appears smack in the middle. How would you like to have a symbol in your name? That's almost like Prince with his glyph!

By the way, there's a similar surname where the гҖ… doesn't even produce an exact repetition:

дҪҗгҖ… (гҒ•гҒЈгҒ•)

The next term looks as weird to me as дҪҗгҖ…жңЁ:

иҚ’гҖ…гҒ—гҒ„ (гҒӮгӮүгҒӮгӮүгҒ—гҒ„: rough, wild)

It seems that if a гҖ… belongs anywhere, it needs to go at the end of a word, as with жҷӮгҖ… (гҒЁгҒҚгҒ©гҒҚ: sometimes) or this fun term from essay 1187 on йҡ… (corner; inconspicuous place):

йҡ…гҖ… (гҒҷгҒҝгҒҡгҒҝ: every nook and cranny; everywhere)

The symbol does fall at the end of the following word from essay 1415 on дёҲ (strong; measure (of length or height); only):

еӨҡеЈ«жёҲгҖ… (гҒҹгҒ—гҒӣгҒ„гҒӣгҒ„: galaxy of able people; collection of intellectuals)

Even so, this expression looks odd to me because I'm unaccustomed to seeing three kanji precede a гҖ…. Kanjigen says that the жёҲжёҲ means “many and magnificent" and that еӨҡеЈ«жёҲгҖ… means “to have many (able) people, which is magnificent.”

Here's a way to use the term in a sentence:

гҒ“гӮҢгҒ гҒ‘гҒҫгҒӮгҖҒеӨҡеЈ«жёҲгҖ…гҒ®дәәжқҗгҒҢдёҖе ӮгҒ«йӣҶгҒҫгҒЈгҒҹгӮӮгӮ“гҒ гӮҲгҒӘгҖӮ

Well, well well! This is quite a gathering of talent to have under one roof.

гҒ“гӮҢгҒ гҒ‘ (this much); гҒҫгҒӮ (well); дәәжқҗ (гҒҳгӮ“гҒ•гҒ„: talented person); дёҖе Ӯ (гҒ„гҒЎгҒ©гҒҶ: same building); йӣҶгҒҫгӮӢ (гҒӮгҒӨгҒҫгӮӢ: to gather); гӮӮгӮ“гҒ (a colloquial form of гӮӮгҒ®гҒ , where гӮӮгҒ® is a nominalizer)

Another interesting case comes from essay 1237 on е‘ү (to give; (Kingdom of) Wu)):

е‘үгҖ…гӮӮ

If I saw this out of context (or possibly in context!), I would have no idea how to expand it. Here's the way it unfurls:

е‘үгӮҢе‘үгӮҢгӮӮ or е‘үе‘үгӮӮ (гҒҸгӮҢгҒҗгӮҢгӮӮ: being sure)

Most people write this entirely in hiragana, so they don't have to be unsure about a term for "being sure"!

Given all these substitutions, I would have expected to see one in this word:

иӮәз—…з—…гҒҝ (гҒҜгҒ„гҒігӮҮгҒҶгӮ„гҒҝ: patient with pulmonary tuberculosis)

But that wouldn't be possible because each з—… carries a different yomi. The last half of the word, -з—…гҒҝ (-гӮ„гҒҝ: lit. "being sick" but used to mean "sick person"), comes from the verb з—…гӮҖ (гӮ„гӮҖ: to be sick) and combines with иӮәз—… (гҒҜгҒ„гҒігӮҮгҒҶ: lung disease, lung + disease).

It struck me that many disease names must have similar duplications of з—…, so I asked my proofreader if he knew of other examples. He said there really aren't any: "Theoretically one can say жҖ§з—…з—…гҒҝ (гҒӣгҒ„гҒігӮҮгҒҶгӮ„гҒҝ: person with an STD), but we usually prefer the suffix -жҢҒгҒЎ (-гӮӮгҒЎ: having), as in жҖ§з—…жҢҒгҒЎ (гҒӣгҒ„гҒігӮҮгҒҶгӮӮгҒЎ)." This translates directly as "having an STD," but the Japanese use it to mean "person with an STD."

Well, STDs are a hard act to follow, and if I say any more, I'm at risk of repeating myself!

Have a great weekend!

Comments