Watercress, Windows, and Wangari

I found a product title on Amazon Japan that made no sense to me:

家庭用 ハーブの水耕栽培キット 窓際族(窓辺でクレソン)

The first words were logical enough:

家庭用 (かていよう: for home use)

ハーブ (herb)

水耕栽培 (すいこうさいばい: hydroponics; aquaculture; water culture; tank farming)

キット (kit)

Well, it's not that I fully understand the definitions of the third term, but I can tell that it involves growing plants in conjunction with water, and that's good enough for now!

I'm also intrigued that although the 庭 at the heart of the first word means "garden" or "yard," these plants will be grown indoors. The idea of the garden gets swallowed up in 家庭 (かてい: home, family, household), bringing all the activity inside.

So where exactly will the plants grow? The next terms might convey the answer:

窓際族 (まどぎわぞく: useless employees (shunted off by a window to pass their remaining time until retirement))

窓辺 (まどべ: by the window)

クレソン (watercress)

But what's going on with the first definition? I was stumped (to use another plant term) until I summoned my proofreader, who explained that the product name involves wordplay.

The herb クレソン (which comes from the French cresson and means "watercress" in English) needs light to grow well, so people place it near the window (窓際 or 窓辺). Here's what the plant looks like:

Much to my surprise, Japanese companies use window locations for something else—useless employees! That is, everything important happens in the middle of the room at a Japanese company. People who have ceased to be productive can sit by the window and stare out at the scenery for the rest of their employment.

Perhaps that was truer in 1978, when many companies treated unproductive employees that way. As a result, 窓際族 became a buzzword, one that the Japanese now use half seriously, half jokingly. Because it's difficult to fire people in Japan, some companies go so far as to create a separate department for unvalued employees, giving them very few assignments while also forbidding them to kill time by doing anything unrelated to company work. It sounds like a Greek torture, and in fact this treatment can be considered a kind of harassment.

I wondered how long this sort of arrangement could last. After all, a 30-year-old can be just as useless as a 60-year-old. Would a young slacker end up staring out the window for decades? Not to worry; 窓際族 implies that the person is fairly old—at least middle-aged. Some dictionaries say so explicitly with regard to 窓際族, whereas others define the word only as "employees with a position but without substantial work."

It fascinates me that, of all the places to put an unwanted employee, Japanese companies would choose a window. That couldn't be more different from Western organizations, where a window office is coveted and a corner office (with multiple windows) is prime real estate. I suppose Westerners are like watercress, craving a window and some sunlight!

Incidentally, the watercress photo above scored its own prime real estate on the front of the newest essay, which also involves growing plants.

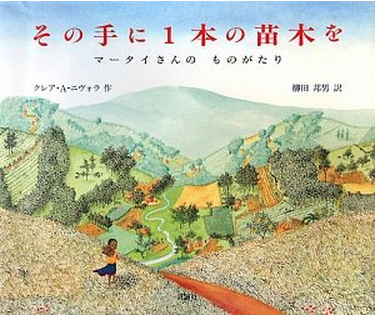

This book cover appears in the essay, too:

I captioned it as follows:

❖❖❖

A book originally published in English as Planting the Trees of Kenya: The Story of Wangari Maathai features 苗木 (なえぎ: sapling; young tree) in its translated title:

「その手に1本の苗木を」

Hold a Seedling in That Hand

手 (て: hand); 1本 (いっぽん: one long, thin thing)

「マータイさんのものがたり」

Maathai’s Story

ものがたり (物語: story)

The book is a biography of environmental and political activist Wangari Maathai (1940–2011), who won the 2004 Nobel Peace Prize.

A reader’s review on Amazon does a great job of summarizing the book and explaining the role that seedlings play so I’ll present the comment in full (minus the typos I fixed):

This beautiful story of the Green Belt Movement in Kenya launched by Nobel Peace Prize winner Wangari Maathai details how she grew up appreciating nature and its bounty, attended college in America and studied biology, and then returned to her homeland only to find that new farming practices threatened the health and well-being of her fellow citizens. Although the people were understandably inclined to blame the government for their deteriorating situation, Wangari encouraged the women to instead plant trees: to gather seeds, dig for water, and nurture seedlings. “All this was heavy work, but the women felt proud. Slowly, all around them, they could begin to see the fruit of the work of their hands. The woods were growing up again.” Wangari “taught the children how to make their own nurseries. She gave seedlings to inmates of prisons and even to soldiers.” Since Wangari began in 1977, over “thirty million trees have been planted in Kenya”—an impressive feat. Lovely watercolor paintings illustrate this simple inspiring story: village scenes show women and children listening to Wangari explain her proposal, and an awesome double-spread shows a line of people marching in an endless line, carrying seedlings and tools for planting.

❖❖❖

Learning about a Kenyan via my study of 苗 was unexpected enough, but two more surprises followed. First, while cleaning my office on Thursday, I stumbled across a New Yorker article from 2011 on deserts and "desertification." I tore into it right away. On Monday I'll write essay 1700 on 漠 (desert), and when that happens, I don't want my mind to be a barren landscape on the topic. Fortunately, the article is quite compelling, particularly when it mentions Wangari Maathai! What synchronicity!

The second Maathai-related surprise came when my proofreader told me that she is quite famous in Japan. After winning the Nobel, she visited Japan in 2005 at the invitation of a newspaper company. While there, she learned this word:

もったいない (勿体無い: (1) impious; profane; sacrilegious; (2) too good; more than one deserves; unworthy of; (3) wasteful)

For the first meaning, people use the kanji rendering (in which 勿 is non-Joyo). For definitions 2 and 3, the Japanese use hiragana.

It's the third meaning that left an impression on Maathai. She was struck by the way もったいない conveys the idea of "reduce, reuse, and recycle” all in one word. A Wikipedia article in English explains the rich nuances of the term, saying that it defies exact translation. That piece also delves into Japanese horror at anything wasted.

Meanwhile, a Japanese site says that Maathai worked to turn mottainai into a 世界共通語:

世界 (せかい: world)

共通語 (きょうつうご: common term)

That is, she wanted to popularize the term so that the whole world would use mottainai, becoming more environmentally aware in the process. I don't believe that has happened. What a waste!

Have a great weekend.

Comments