When 文字 Aren't Characters

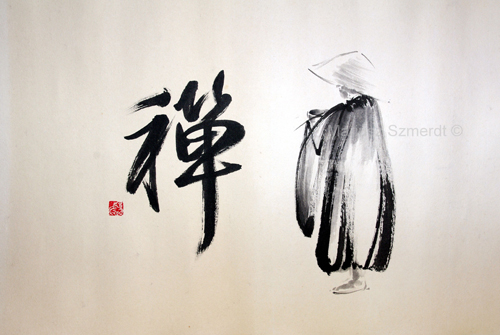

When is a character not a character? Here's one example by the extremely talented artist Mariusz Szmerdt:

Although the part on the left (禅, ぜん: zen) is clearly a kanji, it's also a powerful force to contend with, in my opinion!

If characters were life-sized, our relationship with them would have to change. For one thing, we would find it so much easier to read them! For another, we would take them one at a time, giving them all the attention they each deserve.

On 文字 and -文字 in the Usual Sense

There's another situation in which a character—or more precisely a 文字 (もじ)—defies expectations. Let me explain.

Normally, 文字 has the following meanings:

文字 (もじ; もんじ: (1) letter (of alphabet); character; (2) literal)

For instance, A is a 文字. So is あ. So is 亜 (あ: Asia, to rank next, come after, -ous).

As a suffix, -文字 can still mean "character" or "letter." Some intriguing examples:

人文字 (ひともじ: arranging several people so as to form a character or spell out a message)

八文字 (はちもんじ: (in) the shape of the character 八 (はち: 8))

十文字 (じゅうもんじ: cross)

This last one refers to crosses on churches, as well as the Red Cross. But it originated with the number 十 (じゅう: 10).

-文字 That Aren't 文字

Aside from these things that resemble kanji, there's a group of words in which -文字 has nothing to do with the shapes of characters. Two examples:

寿文字 (すもじ: sushi)

髪文字 (かもじ: hair)

The pattern for forming these words is a little like that for Pig Latin, only backward! You take the first syllable in the yomi (or sometimes the first two) and drop the rest, adding -文字. Here's how that works with the same examples:

寿司 (すし: sushi) —> 寿文字 (すもじ)

髪 (かみ: hair) —> 髪文字 (かもじ)

For the most part, this pattern started during the Muromachi period (1333–1568). High-class ladies of the Imperial court (who were called 女房, にょうぼう) created these terms as part of a code.

According to my proofreader, these women had a few incentives for inventing such a language:

1. To come across as elegant, sophisticated, womanly, and witty.

2. To make it so that lower-class employees and outsiders could not understand them.

3. To express the names of everyday objects in a roundabout way.

As time passed, the lexicon of this code expanded. Furthermore, some of the words spread to lower-class employees in the latter part of the Muromachi period. During the Edo era and afterward, women in town also picked up some of this lingo.

No one knows why these women chose -文字 as part of the code. Most likely, this -文字 literally meant "kanji characters," even back then. It served as a sort of stand-in for any word they wanted to hide.

It's also worth considering that people began interweaving kanji and hiragana during the Muromachi era. Before, in the Heian period (794–1185), they used only hiragana. To people of the Muromachi period, especially to the court ladies, the suffix -文字 must have seemed fresh and attractive, and it probably made them feel elegant to use such a word.

Those two theories have come from my proofreader. Here's my take: The kanji system is one of the greatest codes in the world. If those women were looking for a code word, they couldn't have chosen one better than -文字.

Lots o' Examples

This is the best-known example of this pattern:

杓 (しゃく: ladle) —> 杓文字 (しゃもじ: rice scoop or paddle)

Note that the meaning of the word changes; a 杓文字 is a very specific type of ladle, as the link shows. Of all the -文字 terms I'm presenting here, 杓文字 is the only one in common use today, according to one proofreader, who hadn't heard of the others. In fact, the dictionary labels some of them as archaic. Another proofreader (who is several decades older) says that some of these terms have survived to modern times, noting that both men and women today use these -文字 words either seriously or jokingly.

Here are several other examples:

Food and Animals

烏賊 (いか: squid) —> 烏文字 (いもじ)

狐 (きつね: fox) —> 狐文字 (きもじ)

魚 (さかな: fish) —> 魚文字 (さもじ)

鯖 (さば: mackerel) —> 鯖文字 (さもじ)

鯉 (こい: carp) —> 鯉文字 (こもじ)

小麦粉 (こむぎこ: flour) —> 小文字 (こもじ)

Note that the last four listings yield two sets of homophones (さもじ and こもじ, respectively). Note, too, that 小文字 (こもじ) can mean "lowercase letters" in a way that's unrelated to the code.

Feelings

恥ずかしい (はずかしい: shameful, embarrassing) —> 恥文字 (はもじ)

People

母 (かか: mother) —> 母文字 or か文字 (かもじ)

Long ago, people read 母 as かか. Even today, this yomi persists in the slang term かかあ, though no one uses 母 for that.

Terms for the Code

Here's the way to refer to this code:

女房詞 (にょうぼうことば: the encoded language of court ladies)

Incidentally, ことば is a non-Joyo kun-yomi for 詞, and my proofreader considers it a "poetic" yomi.

The language features two types of alterations to words, the first of which we've just discussed at length:

1. 文字詞 or 文字言葉 (もじことば: term created by retaining the 1st syllable (or the 1st 2 syllables) of a word and adding -文字)

2. word preceded by the elegant honorific お-, such as お腹 (おなか: stomach) and おにぎり (rice ball, sometimes with a filling)

Aha! We have the women of the high court to thank for the honorific お-!

By the way, the following term uses both kinds of alterations:

お目にかかる (おめにかかる: happy to see someone, particularly you) —>

お目文字 (おめもじ)

What a bonanza!

Cateji

Here's a final example of when a 文字 isn't quite what you'd think it would be:

This is a famous print by woodblock artist Kuniyoshi Utagawa. Here, cats are entangled with catfish (the dark swoops), helping to form the word なまヅ (catfish). The title of the piece includes the word ateji. Because the cats and catfish are serving as stand-ins for hiragana, I prefer to call this artwork an example of cateji!

There's a lot more information about this picture, about Kuniyoshi, and especially about cats in essay 1742 on 猫 (cat), which just came out today:

As if 22 pages on cats weren't enough, I've also just reissued essay 1028 on 猿 (monkey), which is FREE. I've added 29 photos of monkeys and of signs about monkeys. Be sure to check it out! And have a great weekend!

Comments