Wist(eria)fulness

My wisteria obsession continues. As with any deep feeling about nature, it brings euphoric awe as well as sadness that the blooms can't last forever (and that nothing can).

So acute is my anxiety about the inevitable end of wisteria season that I became convinced that "wisteria" and "wistfulness" come from the same place linguistically. As with so many, many things, I was quite wrong. "Wisteria" was named after a man, Caspar Wistar, and what a strange name he had! Meanwhile, one can trace "wistfulness" back to "wist," an obsolete word meaning "quiet, silent, attentive." See, that would have fit so well with the quiet contemplation that wisteria inspires. I do wish Caspar hadn't come along and disrupted my theory!

At any rate, I want to share a few more tidbits that I happened upon as I wrote the newly released essay 2078 on 藤 (wisteria).

Let's start with a quiz. Here's a plant called thoroughwort:

Photo Credit: Koba-chan

The Japanese name of this plant includes a word for an item that the Japanese have traditionally worn. Does the flower shape remind of you any garment? Here are your choices:

a. 帯 (おび: kimono sash)

b. 袴 (はかま: men's divided skirt)

c. 草鞋 (わらじ: straw sandals)

d. 褌 (ふんどし: loincloth; male underwear)

Of these kanji only 帯 and 草 are in the Joyo set. Sorry to have slipped off into forbidden territory, but it was so tempting ...

I'll block the answer with something wonderful that I discovered this week right near my office.

On the other side of a large public parking lot, this long wisteria hedge goes along an alley. At the end one finds another parking lot and the unkempt backs of buildings. But look what's just across the alley:

Photo Credits: Eve Kushner

Here's the answer:

b. The word is 藤袴 (ふじばかま: thoroughwort), which breaks down as wisteria + hakama (men's formal divided skirt).

According to several sites, the flowers of the 藤袴 have a color similar to that of the 藤 plant, and the petals are shaped like 袴—hence the name 藤袴. I love the creative thinking!

Speaking of loose clothing, I knew that the robes of Buddhist monks could be saffron, because essay 1821 on 墨 (black inkstick) linked to a page showing the spectrum of colors in Buddhist priests' outfits across Asia. However, it never occurred to me to think about the source of that yellow color until I stumbled upon this word in essay 2078:

藤黄 (とうおう: gamboge; gum resin from various Asian trees of the genus Garcinia, especially G. hanburyi, used as a yellow pigment and as a cathartic; yellow; yellow-orange) wisteria + yellow

At first I understood almost nothing of the English here. There might as well have been no definition! But as English Wikipedia explains, "gamboge" is the saffron or mustard-colored pigment used to dye the robes of Buddhist monks. This pigment comes from the resin of the gamboge tree of Asia.

Continuing with the matter of what people wear—and vocabulary acquired while working on the 藤 essay—I have learned about decorative hair ornaments known as kanzashi (written in kanji with the non-Joyo 簪). Depending on the month, women (particularly geisha and apprentice geisha) bear different flowers in these hairpins, such as wisteria or iris in May. A photo shows just how elaborate a wisteria kanzashi can be, making the most of this glorious long, purple vine.

If you're wearing any of these things—hakama, saffron robes, or kanzashi—you don't want to be in a cyclone (well, who does?), and you particularly don't want to be anywhere near the Fujiwara effect. This has nothing to do with wisteria, despite the first kanji in this term:

藤原の効果 (ふじわらのこうか: Fujiwara effect) Fujiwara (1st 2 kanji) + effect (last 2 kanji)

Rather, 藤原 is a common surname, and this word refers to a phenomenon that a man named Fujiwara identified in which two storms (especially tropical cyclones such as hurricanes and typhoons) spin around each other.

As long as we're talking about twisters, the wisteria vine twists upward as it grows, and two main types of wisteria in Japan twist in opposite directions! You can see this in the first two photos on a site.

Maybe I should have twisted this discussion in another direction because I also want to tell you something about the name Fujiwara. It belonged to an influential family known as follows:

藤氏 (とうし: Fujiwara clan) wisteria + suffix for surnames

The first man to take this name had a granddaughter who became the emperor’s concubine, and their son became the emperor. This sort of behavior was quite intentional on the part of the Fujiwara clan. They aimed to marry into the imperial family so as to become more powerful. And when one of their daughters entered the palace as a princess or concubine, the clan also sent in talented women (such as the great writers Lady Murasaki and Sei Shonagon) as the daughters’ servants to win the imperial family’s favor. “Servant” sounds lowly, but these talented women (known as ladies-in-waiting) were assistants and companions to those they served. Vital parts of the court, the ladies-in-waiting were members of a salon. (Apparently, people in power sought to outdo each other by assembling the best salons possible.) These women’s contributions ended up enriching Japanese culture immeasurably.

To me it has felt completely enriching to have all these bits of information trail off from the wisteria essay just as a purple wisteria raceme (another new word!) trails off from a vine. I'm sad to see the essay fade out of my life, just as I'll be sad when the purple blooms all around me fall to the ground, the vines fading into the background. It's already starting to happen.

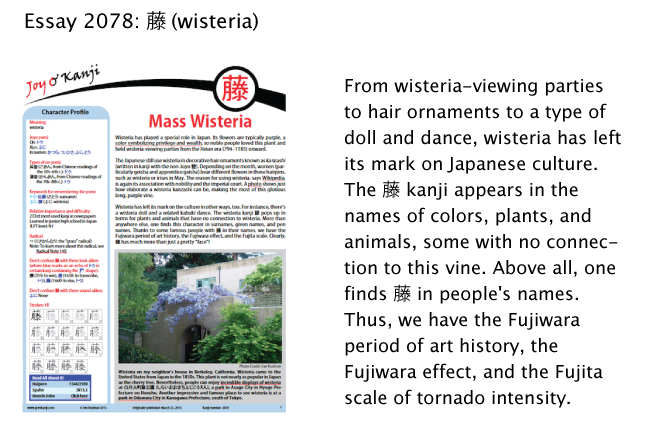

For the moment, though, essay 2078 is brand-new, so there's only cause for celebration! Here's a preview:

Have a great weekend!

Comments