Writing Down Everything

I've been giving a lot of consideration to how I'm spending my time and how I'm stretched way too thin. I know I should jettison some obligations, but which ones and why? My line of inquiry quickly raises questions about the value of Joy o' Kanji. Is this a good way to spend the rest of my life? At the expense of what else?

Asking such questions feels like heresy. Not asking them feels like idiocy.

With all that in mind, I was thrilled to find a wonderful article from the New Yorker (October 16, 2017) called "How to Be a Know-It-All: What You Learn from the Very Short Introduction Series."

Kathryn Schulz's beautifully written piece starts by telling us about a vast project. Oxford University Press is publishing Very Short Introductions, a series of shortish books (roughly 120 pages each) that serve as primers on a seemingly infinite array of topics: from mountains to the Mongols, from Hinduism to autism, from crime fiction to fascism, from the druids to the devil. Collectively, the series is like an encyclopedia, though each topic becomes a book. The in-house list of subjects to cover is currently 1,215, but the intended scope is limitless.

Does this sound familiar? My mind goes right to Joy o' Kanji, of course, and to the aspect of my essays that excites me most. Beyond the way they teach kanji and Japanese, and beyond the joy, curiosity, and wonderment that I hope they inspire, I love how each essay is a portal into at least one topic. As I cover the Joyo set, I therefore stand a good chance of exploring just about everything.

In a sense, I'm writing an encyclopedia. It's no surprise, then, that I want to hear about others' attempts to do the same, and Schulz delivers the goods. After introducing the Introductions, she explores the history of human attempts to write down everything.

She goes back to Pliny the Elder, a Roman statesman and author who wrote the 10-volume Natural History, with life itself as his very topic. Schulz calls that project "one of the earliest-known efforts to record all available human knowledge in a single work." He essentially invented the genre of the encyclopedia, she notes, also explaining that that term literally means "circular education," the circle being the kind we have in mind when talking about a well-rounded education.

Unfortunately, she says, "he was killed, like a cat, by curiosity." Though he was an expert on volcanoes, he went for a better look at the Pompeii eruption in 79 C.E., only to have its poisonous gases kill him within 48 hours.

Schulz then mentions some who created later encyclopedias, including the following:

• Eighth-century Islamic scholars, who produced works about medicine and science among other things.

• The Song dynasty (960–1279) of China, which oversaw the creation of the Yongle Encyclopedia, a century-long project involving 11,095 volumes! (Hmm, Wikipedia attributes that work to the Ming dynasty and says the project went from 1403 to 1408. The scholars did incorporate 8,000 ancient texts, so it's not as if all the writing happened in five years. Anyway, I'm confused!)

• Vincent of Beauvais, a 13th-century Dominican friar in France who compiled The Great Mirror, an 80-book series that attempted to summarize all practical and scholarly knowledge.

• Denis Diderot and Jean le Rond d'Alembert, who published the 18,000-page Encyclopédie in the latter part of the 18th century.

That last work was particularly impressive in being structured according to the different ways in which the mind engages with the world—namely, memory, reason, and imagination. Schulz says that this structure democratized topics, "humbling even the most exalted subjects."

She writes, "It is to Diderot's Encyclopédie that we owe every modern one, from the Britannica and the World Book to Encarta and Wikipedia." Moreover, she writes, Diderot's series made it possible for anyone to have access to information, not just the elite class. (I suddenly realize that I've always taken that access very much for granted.) Schulz says that as with the For Dummies series, the hopeful idea underlying the Encyclopédie is that "what someone can teach, anyone can learn."

And oh, what one can learn from encyclopedic approaches! Schulz notes that with the Very Short Introduction to teeth, one comes across a "considerable amount about evolution, biodiversity, biology, ecology, paleontology, and even physics." Schulz puts it well when she refers to the idea of "carving up the world," one topic at a time.

And there again we have the Joy o' Kanji portal idea!

Her piece shines most when she considers what we get out of encyclopedic treatments. Why is any individual topic important, whether it's Russian literature or the Silk Road? "What do we gain or hope to gain by reading books about all this stuff?"

She brilliantly observes, "There's a fine line between being full of information and full of oneself."

I get a kick out of that bit whenever I think of it! What a fine line she wrote!

She asks whether such knowledge makes us happy. No, she notes, Diderot suffered poverty and a prison sentence.

She wonders whether encyclopedic knowledge makes us wise. "Not always. You can know everything there is to know about volcanoes and still die in one."

She wrestles with the idea that knowledge is power, observing that projects of an encyclopedic scope often exist to promote a certain ideology or to spread values in an imperialistic way, dictating to the entire world what is worth studying. (Yes, but the world needs to know how cool kanji are!)

Not content with having plumbed the depths of this investigation, she then goes deeper, considering whether knowledge makes people behave better. She comments that "it's impossible to shake the notion that knowledge is extraordinarily important" and that knowledge has a "good-faith relationship to reality"!

Finally, she arrives at the simple and reassuring conclusion that you can't have too much knowledge. (I recently told a male friend about a personal health issue and wondered it if were TMI. He said he didn't see "I" as something you can ever have "TM" of!)

Schulz ends with an extremely strong argument—namely, that "everywhere we look, ... there is something to provoke our curiosity, some sliver of existence that we want to understand." And at their best, she says, encyclopedic projects flow forth from an all-encompassing love of life.

Yes, that's it! That's exactly what I feel about Joy o' Kanji! I could not have said it any better.

It holds, then, that I could not be living any better than by dedicating myself to this enormous project. And yet ... I skipped work last Sunday to take a road trip to three beloved beach towns. It was 78 degrees (in February!), and I had the chance to spend the day with someone I've longed to reconnect with, an experience that felt pretty damned life-affirming!

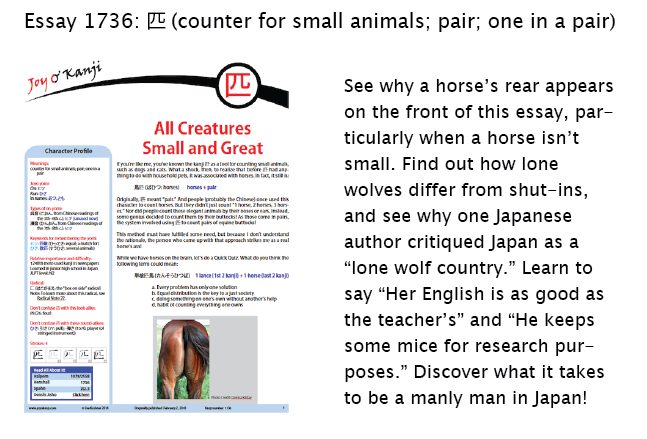

Let's jump now from this macro approach to human existence to a micro view of a tiny topic. I'm talking about 匹, a kanji that enables us to count small animals! Fittingly, my essay about 匹 came out on Groundhog Day! Here's a sneak preview:

Catch you back you here next week!

❖❖❖

Did you like this post? Express your love by supporting Joy o' Kanji on Patreon:

Comments