Younger Sibling Syndrome

I'm sure you know about the younger sibling syndrome. We, the little sisters and brothers, are the ones who wore hand-me-downs for a dozen years or more. We're the ones whose parents took just five pictures of us in our early years, despite having filled albums with photos of their firstborns at that age. We're the ones who had the smallest bedrooms because, you know, there's a concept of primogeniture. That legal term may theoretically involve matters of inheritance, but what the word apparently means in daily practice is that you don't dare question your elder sibling's divine status relative to your own lowly one!

In a sense, I grappled with the younger sibling syndrome in the kanji sphere this week. That is, I kept encountering alternate (i.e., less important) kanji renderings of words. Though there's nothing new about that (just as a younger sibling is nothing new!), two issues arose that I'd never run into before ... or so I thought!

1. Nuances Can Change as You Go Down the Line

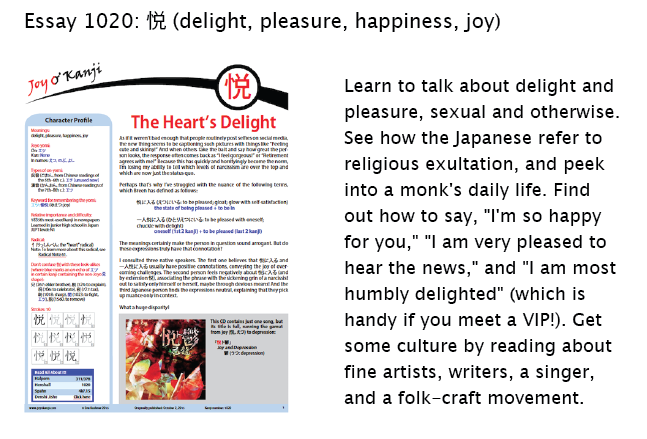

Yesterday I published essay 1020 on 悦 (delight, pleasure, happiness, joy). Although this kanji has only one Joyo yomi—namely, エツ—people do use its non-Joyo kun-yomi:

喜び or 慶び or 悦び or 歓び (よろこび: (1) joy; delight; rapture; pleasure; gratification; rejoicing; (2) congratulations)

The main way to write this word is 喜び, but each of the other renderings serves its own purpose.

For instance, people frequently use 慶び (the second version) in business contexts. Correspondence from one company to another typically starts this way:

貴社ますますご清栄のこととお慶び申し上げます。

We are pleased to know that your business is doing better and better.

貴社 (きしゃ: your company, an honorific term); ますます (increasingly);

清栄 (せいえい: your prosperity); -申し上げる (-もうしあげる: auxiliary verb expressing humbleness)

In this set expression, よろこぶ almost always appears as 慶ぶ, which sounds rather formal.

As for 悦び (the third version), it’s rare, but it does pop up here and there, including in the titles of two erotic historical romances written by an American and translated into Japanese.

The third and fourth versions of よろこび (悦び and 歓び) can sound sexual, depending on the context.

All in all, says my proofreader, people use different renderings to indicate subtle differences in nuance.

What an eye-opening point! A second, third, or fourth kanji version might not just be "lesser than." Instead, it might contribute a special flavor to the discussion.

I asked my proofreader for other examples of this phenomenon, and he mentioned the verb きく:

聞く: to listen, hear

聴く: to listen to music; listen to someone carefully

訊く and 尋く: to ask a question

By the way, 訊 is non-Joyo.

Oh... what a letdown! Seeing the issue in that context has made realize that it's not new to me at all! In fact, on pages 130 and 131 of Crazy for Kanji, I addressed the various "shades of meaning" that a word can have!

Perhaps what's new to me with よろこび is seeing someone present a string of renderings and practically devise a strategy for which one to use in order to achieve a certain effect. My experience has been closer to this: "Danger ahead! Do not—I repeat, do NOT—mix up the two types of はじめ (初め and 始め, which both mean 'beginning') or else terrible things will befall you." It's all been about avoiding mistakes. It never occurred to me that I could survey kanji that have overlapping meanings and select the one that benefits me most.

Maybe in the end this discussion is about feeling powerful or powerless (which brings us back to the sibling struggle)!

2. Substitutive Kanji

Last Sunday night I returned from a nine-day road trip, and the very next morning I embarked on my usual "Monday Marathon," a daylong essay-writing session. Before the trip, I realized that that Monday would be quite challenging. I would be way behind and not terribly sharp, so I shouldn't tackle the difficult kanji I had scheduled for that day. I therefore arranged to write about 錮 (1951: imprisonment), a kanji associated with only one word! Here it is:

禁固 or 禁錮 (きんこ: imprisonment; confinement)

Notice anything? It took me quite awhile to spot the issue. (As predicted, I wasn't too sharp after days in the blazing heat of Las Vegas, which seems to be situated on the surface of the sun!)

Eventually, though, I was flabbergasted to realize that although 禁錮 is the main way in which 錮 exists in Japanese writing, the primary version of きんこ doesn't include our star kanji! People prefer to end that word with the much simpler 固.

That's ludicrous to me because 錮 means "imprisonment," whereas 固 (476: solid, firm; to harden) doesn't. The only reason 禁固 became the preferred rendering is that 錮 didn't join the Joyo set until 2010.

As I learned, this kind of usage involves so-called 代用漢字 (だいようかんじ: substitutive kanji). Digital Dajiisen explains the concept this way: when a word includes a non-Joyo kanji with a complex appearance, the Japanese sometimes swap in a simpler-looking Joyo character with the same reading (usually an on-yomi, I would imagine). Daijirin (at the same link) notes that the substituted kanji should also be similar in meaning.

Here are some examples:

• Initially, people rendered にっしょく (solar eclipse) in kanji as 日蝕. The preferred version is now 日食, as 蝕 (eclipse) is non-Joyo. So we have something eating (食) the sun (日), which is pretty damn cool if you ask me! That is, this substitution makes enough sense semantically. Also, 蝕 and 食 share the yomi of ショク.

• The same 蝕 kanji (this time with the meaning of "erode") also factored into 腐蝕, the original rendering of what is now 腐食 (ふしょく: corrosion, erosion, rot). Eating away at something causes corrosion. I approve of this change!

• The early rendering of きしょう (rare, scarce) was 稀少 but became 希少. The non-Joyo 稀 (キ) means "rare," and so can 希 (キ), though it more commonly translates as "hope." I'm lukewarm about this decision.

• Whereas people once wrote 車輛, they now write 車両 (しゃりょう: vehicles, cars). In this way, they shifted from the non-Joyo 輛 (リョウ: counter for large vehicles) to 両 (リョウ: both), which makes little sense semantically. Thumbs down. They got rid of the car in the second kanji!

As you can see, the more streamlined Joyo replacement may also physically resemble the complex one. However, that's not always the case:

聯合 → 連合 (れんごう: union, alliance)

編緝 → 編集 (へんしゅう: editing)

綜合 → 総合 (そうごう: general)

掠奪 → 略奪 (りゃくだつ: plundering)

諒解 → 了解 (りょうかい: understanding, agreement)

All the "rejected" kanji are non-Joyo.

Anyway, 禁固 and 禁錮 constitute a substitutive pair, and as it turns out, the Japanese have been making this particular swap for a long time. Wikipedia says that prior to World War II, 禁錮 was the official rendering, but people sometimes used 禁固. At that time it wasn't a matter of which character was Joyo; it was just an issue of simplicity.

After I grasped all this, a new question arose: Can we call this substitution ateji? I mean, using 固 in a term for "imprisonment" is clearly a mismatch of meanings.

One could call it ateji, said my proofreader, but he then pointed out a grey area. "Ateji" is the opposite of "official," in a sense. And if a word such as 禁固 has become the official rendering (as it has), it can't very well be considered ateji.

To put it another way, an ateji status has a shelf life. When a term has been around awhile, that ateji rendering often becomes "just the way it is," not anything special, no matter how badly mismatched its kanji are with meanings or readings.

Shifting the metaphor from expired food to a beloved children's book, we could say that some ateji are like the Velveteen Rabbit. After very many years of love and rough handling, a bunny becomes careworn but unquestionably real. By contrast, a new stuffed animal looks a bit contrived!

Have a great weekend! And be sure to check out the new essay 1020. A sneak preview is just above.

Oh, one more thing. If you have multiple kids, please give the younger one(s) an extra-large piece of cake this weekend just to see steam come out of the elder one's ears. And send me a picture of that. I would find it quite gratifying.

Comments