106. The "White" Radical: 白

The "white" radical 白 is on duty in just five Joyo kanji, and it means "white" in exactly none of them! Well, to be accurate, it somewhat whitens the etymology of the 白 kanji, but "white" isn't the primary thing that shape represents.

Photo Credit: Janet Walker

The kanji are 白川郷 (しらかわごう), the name of a famous historic village on the border between Gifu and Toyama Prefectures on Honshu.

The Vitals of the 白 Radical

Before delving into etymology, let's look at the basics of the five-stroke 白 radical. It's called the "white" radical in English, しろ in Japanese (just as the autonomous kanji 白 has the kun-yomi of しろ). This character can appear on the left side of kanji, on top, or on the bottom, as these examples respectively show:

的 (551: mark, target; adjectival ending)

皇 (861: emperor)

皆 (1064: all, everything; everyone)

Wherever it is in a character, this radical maintains the name しろ.

The Etymology of 白

Let's examine the history of the character that doubles as the "white" radical:

白 (65: white)

Henshall says that a slightly different version of this shape represented a "pointed thumbnail," one that showed the exaggerated length that was in vogue in ancient China. Here's what that old character looks like on Sears's page:

This shape served not only as a pictograph but also acted phonetically to express "white" while suggesting "paleness relative to the skin," says Henshall. Ah, yes, a nail is lighter than the surrounding skin.

However, he says, some evidence shows that the old pictograph was of an "acorn" with a whitish interior. If that's true, he concludes, "two pictographs may have coexisted."

In his analysis of 楽 (218: pleasure; music) he also notes that 白 later came to mean "hundred," "white," and maybe "principal" (as in "main, primary").

Photo Credit: Eve Kushner

Though Henshall associates 白 with "hundred," our kanji is socializing with 十 (ten) in this cafe sign. Here's how the words break down:

神田 (かんだ: area near Tokyo Station)

白十字 (はくじゅうじ: lit. "white cross")

One reads this 白 with its Joyo on-yomi of ハク.

This cafe must be a good place to prep for math tests! Actually, one blog post explains that both the exterior and interior of this cafe look like a chapel, which may be the origin of the 十字 (cross).

The 白 in 百

If 白 meant "hundred" at some point, then surely that tells us everything we need to know about this kanji:

百 (67: hundred)

But no, that's not the case! This character combines 一 (one) with 白, which means "thumbnail" here, says Henshall. He notes that in ancient times, the thumb represented "hundred." Ah, there's the connection. At any rate, the 白 doesn't mean "white" in 百, and it doesn't even directly signify "hundred." That happens indirectly.

Photo Credit: Corey Linstrom

The photographer says that Paimen is the name of a really good Kyushu-style ramen shop. As for the smaller kanji, one reads them vertically. The 極楽 (ごくらく) means "paradise" and includes 白 as a component! And 汁麺 (しるめん) means "noodles in soup," which can refer to ramen, udon, or soba.

The 白 in 的, 皇, and 皆

Thus far, we've seen two etymologies in which the 白 radical doesn't actually mean "white." What about the other three kanji in which it's the on-duty radical? No, I'm afraid we're out of luck there, too! Let's evaluate each one.

• 的 (551: mark, target; adjectival ending)

Henshall says that this 白 means "conspicuous," whereas this 勺 (usually "ladle" or "scoop") represents "select" and by extension "set apart." Something conspicuous and set apart is "a target," he says. Setting something apart gave rise to the idea of "classification," which in turn inspired the concept of "likeness." And the -like concept became a common way of forming adjectives, he says. By the way, Henshall notes that some old forms of 的 include 日 (sun, bright) instead of 白, so our radical may not have been in this character originally.

• 皇 (861: emperor)

This character initially referred to a "king's crown" or "ceremonial headpiece," says Henshall, later coming to refer to the person wearing such an item—namely, a "ruler" or "emperor." Appropriately enough, the old form showed a "king" (王) and his crown, so our radical has nothing to do with whiteness here.

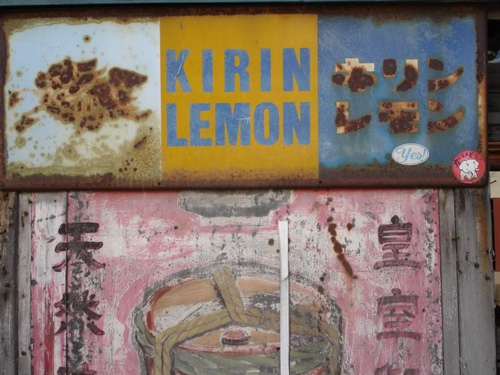

Photo Credit: Sui Feng

It seems that the Kirin Lemon drink has nothing to do with the pink sign, which probably says 皇室御用達 (こうしつごようたし: purveyor to the royal household) down the right side. The word 皇室 (こうしつ) means "royal household" (note that the top stroke of 皇 is angled the wrong way), and 御用達 (ごようたし) means "purveyor (esp. to the government, royal household, etc.)." The product is likely miso or saké sold in a barrel, and the idea of the ad is that the product must be great because the royal family regularly uses it.

• 皆 (1064: all, everything; everyone)

Henshall says in his newer edition that most scholars take the bottom component in 皆 to have been 曰 (say). He also cites one researcher who instead treats the 白 as a simplification of a character meaning “open mouth.” His experts do at least agree that the 比 on top (originally “two people lined up”) means “compare.” Collectively, the top and bottom halves yield “people line up and exchange words” or “people line up and all say something.” The character later generalized to mean “all.”

Kanjigen has a very different take, asserting that the 白 in 皆 used to be 自, which is how people initially wrote "nose" (now 鼻). However, the 自 in this context means "to do so." Combining 比 (to line up) with 自 (to do so) yields 皆, which symbolizes “everybody is lining up together.”

Here is an ancient form of 皆 on Sears's page:

Whether 皆 once included 曰 per Henshall or 自 per Kanjigen, it definitely didn't include 白. If anyone tells you otherwise, it's as good as whitewashing!