112. The "Stone" Radical: 石

The 石 radical (which goes by the name of いし, just as the 石 kanji does) is much like a stone: durable and just about immutable. That is, the shape of this radical never changes in a kanji. It looks the same in all of these:

研 (272: to grind, polish; research)

破 (767: to break)

砕 (1287: to crush up)

硝 (1405: nitrate; saltpeter)

硫 (1902: sulfur)

Photo Credit: Lutlam

Here we find a word with two instances of the 石 radical!

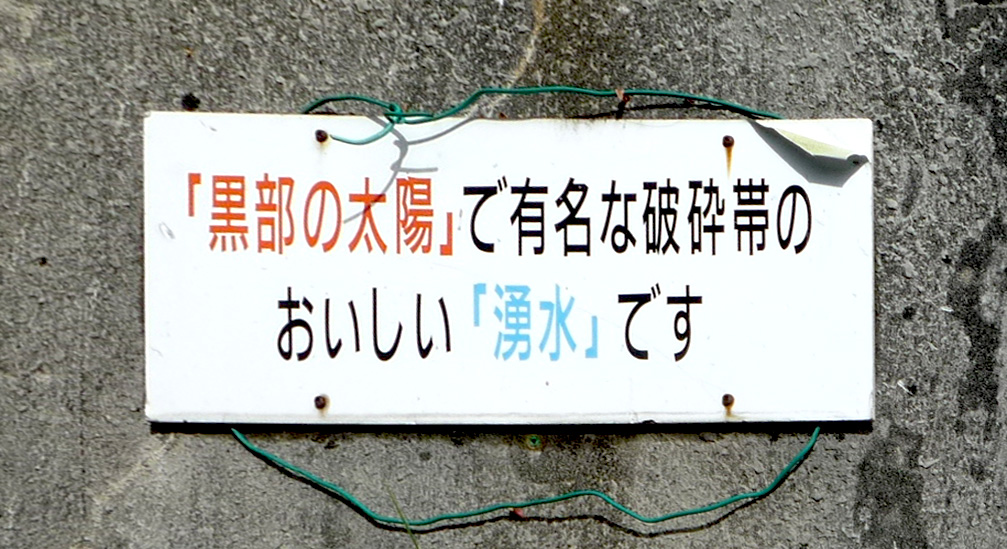

破砕帯 (はさいたい: fracture zone)

This sign at the Kurobe (黒部) Dam in Toyama Prefecture refers to an area or zone (帯) that workers encountered while tunneling under Akazawa-Dake Mountain. The bedrock had naturally broken into pieces (破砕, はさい: crushing) and spewed an enormous amount of groundwater. The "geyser" blocked construction, posing quite a problem for seven months. Now this tourist attraction offers that delicious (おいしい) spring water (湧水, ゆうすい) for free to those who want to drink it.

The 1964 novel 「黒部の太陽 (くろべのたいよう: The Sun of Kurobe)」 tells the story of how they struggled to build this dam, which is the tallest in Japan. Four years later, a popular eponymous movie told the same tale. Thus, the sign says that the movie made the fracture area 有名 (ゆうめい: famous).

In a trailer for the movie, the word 破砕 appears on the screen at 0:44!

Position of the "Stone" Radical

You can almost always find 石 on the left in a kanji, at which point it takes the commonsensical name of 石偏 (いしへん).

Oh, and whenever 石 is on the left, it's always on duty. I can find only three Joyo instances in which the on-duty 石 is not on the left:

石 (45: stone)

碁 (1240: the game of Go; Japanese checkers)

磨 (1831: to polish; brush (teeth); grind, wear away; improve)

In those cases 石 is centered and grounded—certainly trustworthy qualities!

Photo Credit: Eve Kushner

The word in this sign, 達磨 (だるま), means "Bodhidharma." The word 達磨 can also mean "Daruma (doll)." On top of that, this word in its hiragana form often appears in compounds where it refers to something round (e.g., 雪だるま, ゆきだるま: snowman) or something red (e.g., 血だるま, ちだるま: (person) covered with blood). A Daruma doll is both round and red. Finally, in rare cases 達磨 can mean "prostitute"!

The "Stone" Radical, Off Duty

Here are the few Joyo cases in which 石 serves as a mere component:

岩 (249: rock; boulder)

拓 (1554: to open up (land); rubbed copy)

妬 (2076: envy; jealous)

The Stoniness That the "Stone" Radical Brings to Characters

Whether it's on duty or off duty, 石 contributes a stony meaning to nearly every kanji in which it appears. Check out all the stoniness inherent in these characters:

砂 (869: sand)

硬 (1260: hard)

礁 (1413: reef, sunken rock)

碑 (1731: inscribed stone monument)

Photo Credit: Corey Linstrom

Watch out for 砂 (すな: sand)! Or be very surprised by it when you find it in this beach town near Shimoda, on the Izu Peninsula!

The stony connection has become indirect in a few cases, but the stones lie just beneath the surface:

碁 (1240: Go, a game resembling checkers, though the rules are quite different)

When people played Go with wood, this kanji contained the 木 (wood) component; it was 棋 (1130, which is now associated with 将棋, しょうぎ, Japanese chess). Henshall explains that 石 replaced 木 when Go pieces came to be played with stones, known as 碁石, ごいし.

砲 (1800: heavy gun, gun; cannon)

The 包 part, which usually means "to wrap; envelop," acts phonetically here to express "release" or "discharge." It might also express "encircling, encasing." This kanji originally referred to a primitive cannon that fired small rocks through a tube! So there's your stony connection.

磁 (881: magnetism; magnet; porcelain)

Henshall says that this kanji shows a stone that pulls, perhaps mysteriously—a magnet. When I think of "magnet," I picture a rubbery-looking thing on a refrigerator, so I wondered about the connection to stones. But some stones (e.g., lodestones) do have magnetic properties. And in fact Wikipedia says that "magnet" comes from a Greek word meaning "stone from Magnesia," a place in ancient Greece where they found lodestones. Meanwhile, "porcelain" is just a borrowed meaning of 磁, says Henshall, so even though that material seems stony, it doesn't count etymologically.

確 (634: certain; definite; sure; reliable; accurate; firm)

The two sides represent "rock" and "crested bird," but the part on the right phonetically expresses "hard," says Henshall. Thus, the whole character ended up meaning "hard rock," which became "hard" or "firm" and therefore "reliable" by extension.

With all this reliability, the 石 radical serves as a touchstone and comes across as down to earth in a way that I find comforting.

Photo Credit: Dan Farthing

In this Chinese sign, 破 (767: to break) heads off the second line. The translation should actually be, "Don't ruin the eternal beauty (of the site) because you were temporarily careless." Instead we find something rather different!