All Turned Around

In writing the new essay 1840 on 岬 (cape, promontory, headland), I was surprised to find that for each of their main islands (and doubtless for many others), the Japanese have identified and named the four endpoints—the extremities to the north, east, south, and west. Notice how I sequenced those cardinal directions; I started at the "top" of the "clock" and went around clockwise. In doing so, I broke a cardinal rule, at least in Japan! When presented with the same geographical "clock," the Japanese "tell time" differently. I'm talking about this word:

東西南北 (とうざいなんぼく: east, west, south, north)

I wondered if this had anything to do with the way the ancient Chinese used to read their round coins with square holes.

Photo Credit: Eve Kushner

Spotted in Hong Kong in 2012. To read these coins, move from top to bottom (finding the name of a dynasty or era, indicating when the coin was in use), then right to left (finding a word that meant "currency"). As I wrote on page 163 of Crazy for Kanji, China has produced coins since as far back as 770 BCE. The hole in the middle of such coins enabled people to carry them on strings, rather than in purses.

No, the Japanese sequence differs from the order in which one reads Chinese coins. The Japanese have used the east-west-south-north order since at least 720, which is when someone published「日本書紀 (にほんしょき)」, the oldest chronicles of Japan. That book notes that east and west are one entity, as are south and north.

As for putting east first and south third, Chiebukuro notes that the east is important because that’s where the sun rises. And the south is important because the sun is always to the south of Japan.

Hmm, did Haruki Murakami get the order wrong? In both languages, the title places "south" before "west." Here's the title of his book in Japanese:

「国境の南、太陽の西」

South of the Border, West of the Sun

国境 (こっきょう: border); 南 (みなみ: south); 太陽 (たいよう: sun); 西 (にし: west)

The first part of the title refers to a Nat King Cole song that Nat King Cole never actually sang. If you can understand that, you're equipped to solve the mysteries in Murakami's fiction.

Like 東西南北, other Japanese phrases embody strict sequences that reveal stark differences between East and West (which apparently aren't one entity when you consider things on a global scale!):

白黒(しろくろ: "white and black," which is to say "black and white")

新旧(しんきゅう: "new and old," which is to say "old and new")

貧富(ひんぷ: "poor and rich," which is to say "rich and poor")

紳士淑女(しんししゅくじょ: "gentlemen and ladies," which is to say "ladies and gentlemen")

The same kind of inversion happens for terms such as "upper right":

右上 (みぎうえ: "right upper," which is to say "upper right")

右下 (みぎした: "right lower," which is to say "lower right")

You'll find more such inversions at the same site that supplied these.

Meanwhile, another link issues the following dictum about these phrases in both languages:

その順序は慣例的に決まっていて、勝手に変えることはできません。

The order is conventionally decided and cannot be changed by preference.

順序 (じゅんじょ: order); 慣例的 (かんれいてき: customary); 決まる (きまる: to be decided); 勝手 (かって: arbitrary; one's way); 変える (かえる: to change)

Oh, my! This sets me up mentally for the next essay I'm scheduled to write, which is on 遵 (to obey)!

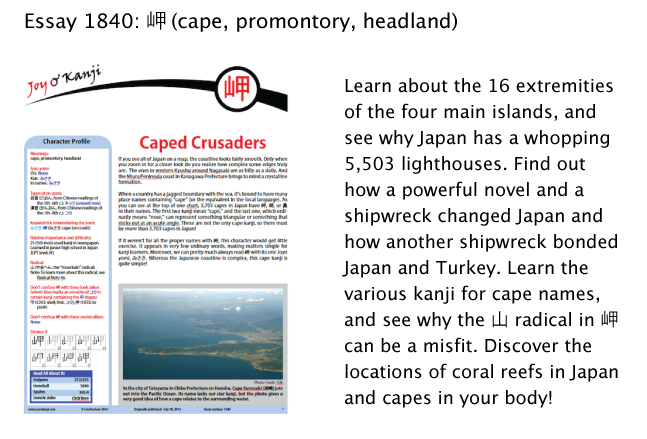

Here's a preview of the newest essay:

Have a great weekend!

Comments