The Dew of the Land

Let's start with a quiz. If 露 means "dew" and 地 means "land," what do you think this term could mean:

露地 (ろじ) dew + land

a. outdoors

b. nostalgic description of the countryside as having pastures that glisten in the morning

c. the name of a beverage brand

d. the name of an amusement park

I'll block the answer with a preview of the newest essay:

Okay, here's the answer:

a. 露地 (ろじ: dew + land) means "outdoors." More specifically, it means "land where there are no roofs and where rain and dew therefore fall directly"! Because most cultivation happens outdoors, this idea seemed funny to me, but the Japanese use 露地 to represent the opposite of greenhouse cultivation.

If you want ろじ to mean "outdoors," you can render it only as 露地, but ろじ has several other renderings, depending on its definition:

1. 路地 or 露路 (ろじ: alley; lane)

2. 路地 or 露地 (ろじ: teahouse garden)

3. 路地 or 露地 (ろじ: path through a gate (or through a garden, etc.))

The latter definitions sound lovely and idyllic!

By the way, I used color-coding to help keep all the complex characters straight.

The word 露地 comes to us from essay 1289, where I found a few more unexpected tidbits. We'll explore them one by one.

1. 別に

Translating the subtitle of the book above gave me a devil of a time. To my surprise, the word that caused the most confusion was one of the simpler-looking ones, though it seemed to have many definitions:

別に (べつに: (1) (not) particularly; (not) especially; (not) specially; (2) separately; apart; additionally; extra)

Turns out, I had it all wrong. As my proofreader explained, "This 別に isn’t a standalone word meaning 'particularly.' It’s a suffix meaning 'by.'" He gave these examples:

カテゴリー別に (カテゴリーべつに: by category)

職業別に (しょくぎょうべつに: by occupation)

男女別に (だんじょべつに: by gender)

So, he said, this book presents landscaping plans and organizes them by tree species. For each species, there's a different plan. Here is the final translation:

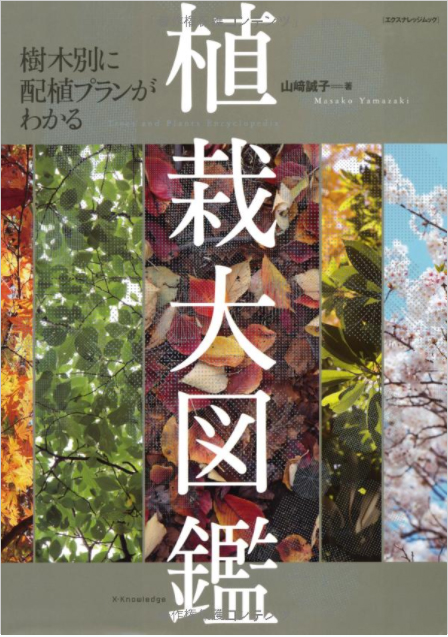

「植栽大図鑑」

Encyclopedia of Growing Trees and Plants

植栽 (しょくさい: growing trees and plants); 大- (だい-: big); 図鑑 (ずかん: illustrated reference book)

「樹木別に配植プランがわかる」

Understanding Strategic Landscaping Plans by Tree Species

樹木 (じゅもく: trees and shrubs); -別に (-べつに: by); 配植 (はいしょく: strategic landscaping)

2. の末

It's so often the little words that trip you up, isn't it? I had that experience again with the headline on this sign. When I saw 末, I looked it up in Breen and found all these options (which I've trimmed down for your convenience):

末 (うら: top end; tip)

末 (うれ: new shoots; new growth (of a tree))

末 (すえ: (1) tip; top; (2) end; close (e.g., close of the month); (3) youngest child; (4) descendants; offspring; posterity; (5) future; (6) finally; (7) trivialities)

末 (まつ: (1) the end of; (2) powder)

Wow! The first two are archaic, so they obviously don't count here. I settled on すえ (finally). After all, the sign contains "finally."

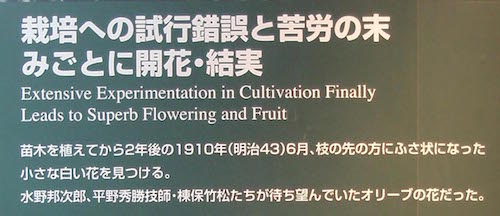

Nope! The yomi was right, but not the meaning. The の末 means "after," said my proofreader. Oh! I had no idea I was supposed to take the の into account! Here's the finalized translation we produced (after considerable trial and error and much hardship):

栽培への試行錯誤と苦労の末みごとに開花•結実

Trial and Error in Cultivation and Hardships Lead to Superb Flowering and Fruiting

試行錯誤 (しこうさくご: trial and error); 苦労 (くろう: hardships); の末 (のすえ: after); みごと (見事: superb); 開花 (かいか: flowering); 結実 (けつじつ: bearing fruit)

3. Countless Farmers

In the cute banner under the yellow flower on this book, we find this puzzler:

百姓 (ひゃくしょう: farmer; farming) 100 (various) + titles

The breakdown I've presented comes from Gogen, which says that the word originally meant “people with various titles,” which was to say “citizens.” Later, 百姓 came to mean “ordinary people” and then “farmers.” Why “farmers”? My proofreader muses, "Chances are, many of us were farmers." Indeed!

Have a great weekend! And be sure to check out essay 1289 on 栽 (planting, cultivating)!

*****

Did you like this post? Express your love by supporting Joy o' Kanji on Patreon:

Comments