Why Did the Chicken Forget to Cross the Road?

I've struck up a correspondence with a Japanese man who likes colorful expressions as much as I do. He happened to tell me that his wife often lobs the following criticism at him:

三歩歩いたら忘れるんだから!

You forget everything in three steps!

三歩 (さんぽ: 3 steps); 歩く (あるく: to walk);

忘れる (わすれる: to forget)

I love the back-to-back instances of 歩, especially because they come with different yomi. But I might have been lost if he hadn't also provided this bit of context for her comment: "We say in Japanese that a chicken forgets everything when it walks three steps."

I didn't know chickens were forgetful! Perhaps they're more so in Japan.

He then said that the Japanese refer to a forgetful person with another chicken tidbit:

鳥頭 (とりあたま: forgetful person) chicken + head

When English speakers refer to chickens and heads idiomatically, it's usually to say that a someone is running around like a chicken with its head cut off. In Japan, even with its head on, a chicken can't seem to think effectively.

Incidentally, the manga artist 西原理恵子 (さいばら りえこ) often reminisces about her childhood in her manga, and she has said that her mother often yelled this at her:「この鳥頭!」 (You airhead!). The artist has incorporated that term into the name of her company.

This chicken insult made me curious about where else 鳥 might pop up unexpectedly in Japanese words, so I looked into the matter.

Toriis for Birds, Toriis for the Bedroom

Even though this word is quite common, it never fails to charm me:

鳥居 (とりい: torii; Shinto shrine archway) chicken, bird + to sit

According to Nihon Kokugo Dai-Jiten, 鳥居 originally meant “perch for a chicken offered to a god.” A chicken?! I've always imagined that this term referred to sparrows or some such! But how in the world would a chicken reach the top of a torii? My proofreader says the chicken was most likely placed there as an offering while still alive, though it's unclear what would have prevented it from flying away. (Yes, chickens can fly! That is, wild ones do. Humans have modified other kinds of chickens so that they've lost that freedom.)

Photo Credit: Christopher Acheson

The famous torii at Itsukushima Shrine on the island of Miyajima in the Inland Sea.

I adore toriis. Simple and yet dignified, they're somehow full of meaning and mystery.

Come to think of it, the front page of Joy o' Kanji has a photo of toriis at Fushima Inari Shrine in Kyoto. The photo shows too many toriis to count, though there are supposedly about ten thousand! Here are some of those arches, along with people who look less than enthralled to be there:

Photo Credit: Christopher Acheson

I've just learned the term for such an inspired design:

千本鳥居 (せんぼんどりい: many torii; torii corridor)

many + long, thin thing + torii (last 2 kanji)

Although people usually count toriis with 基 as a counter, the toriis at Fushima Inari Shrine are a special case, and people use 本, as this term reflects.

Right now, I'm even fonder of toriis than usual because I'm the proud owner of a new "torii" clock! I was heartbroken when my bedside clock died after many years; it had a cool ethnic design that I couldn't hope to replace. But I've done so much better. I found this clock online:

Photo Credit: Eve Kushner

And now I own it! Whenever I walk into the bedroom, my eye goes right to that clock, and my heart takes a happy little leap. As if it couldn't get better, the clock is by Takumi Designs. The 匠 (たくみ: master; craftsperson, artisan) kanji is one of my favorites! I had a ball writing that essay.

Killing Two Birds with One Radical

Talking about clocks brings to mind the cuckoo, which migrates to Japan in the summer and has worked its way into this expression:

閑古鳥が鳴く(かんこどりがなく: (for a business) to be in a slump; for (business) to be slow) cuckoo (1st 3 kanji) + to cry

According to two websites, including one on proverbs, a cuckoo’s cry sounds somewhat lonely. This term therefore came to be used for businesses that aren't attracting people.

It makes me happy to see the "bird" radical 鳥 twice in 閑古鳥が鳴く!

Speaking of duplication, check out the following pair of words:

鳥目 (とりめ: night blindness) bird + eye, eyesight

鳥目 (ちょうもく: money; coin with a square hole) bird + eye

In the first case we have a kun-kun combination. The breakdown suggests that birds see poorly at night. Is this true? Yes, I've confirmed that most birds see about as well as humans at night, which isn't very well. The owl is one of a few exceptions. Perhaps there's a reason so many birds sing in the morning; they're rejoicing at finally being able to see again.

In the on-on duo that we find in the ちょうもく version, the avian connection initially seems much less clear. But this term refers to square-holed coins called 和同開珎 (わどうかいちん), which supposedly look like birds' eyes.

Photo Credit: Eve Kushner

The Hong Kong version of the round coin with a square hole.

Another pair or words provides not a duplication but rather a reversal:

鳥人 (ちょうじん: aviator) bird + person

人鳥 (じんちょう: penguin) person + bird

A person who flies (as a bird does) is an aviator. Makes perfect sense. And then a person-like bird is a penguin! There's some anthropomorphism for you! Of course, the Japanese usually use 飛行家 (ひこうか) for ”aviator" and ペンギン for "penguin."

Tying It All Together

We've seen references to chickens that walk three steps, as well as to many (千) toriis. If we pick out bits and pieces of those terms, we can produce this one:

千鳥足 (ちどりあし: tottering steps; drunken staggering)

plover (1st 2 kanji) + steps, walking

This word with three kun-yomi rolls off the tongue but refers to an uneven gait! According to Wikipedia, plovers are wading birds that hunt with a "run-and-pause" technique. The plover is also called a dotterel, which sounds more like a creature with an uneven, doddering gait.

As for humans who walk with 千鳥足, this term usually refers to those who are drunk (which isn't surprising, given the definition) but could also allude to a style of walking that involves swinging each leg in front of the other. That is, the right leg moves forward while veering way over to the left, and then the left foot advances while going way over to the right. Apparently, plovers walk this way—and I'm told that supermodels sometimes do, as well!

More from the Natural World

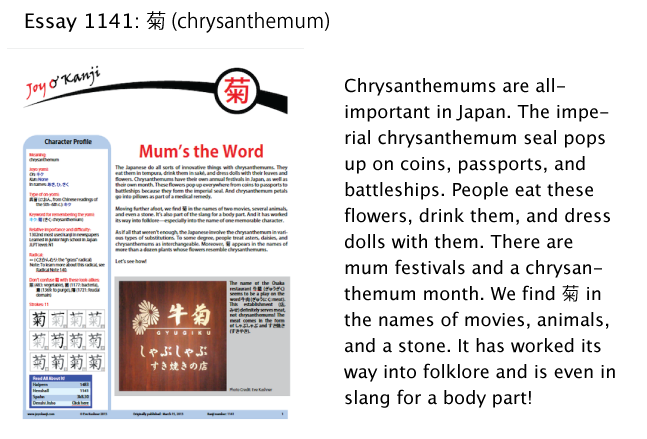

This week's essay draws on the natural world, but it's not about anything with wings. Instead, essay 1141 on 菊 takes you into the world of chrysanthemums. Here's a preview:

Have a great weekend!

Comments